The Port Phillip Kangaroo Coins. This article is currently being updated with new information. Available in February 2026!.

The discovery of significant gold deposits in Australia in 1851 created sudden wealth and stimulated immigration on a vast scale. The Gold Rush transformed the nation, economically and socially, and marked the beginnings of a modern multi-cultural Australia.

No colony was immune from the dramatic effects of the discovery of gold. Those that were rich in gold. And those, such as the colony of South Australia, that was devoid of the precious metal, its economy collapsing due to the mass exit of manpower and currency lured to the Victorian gold fields.

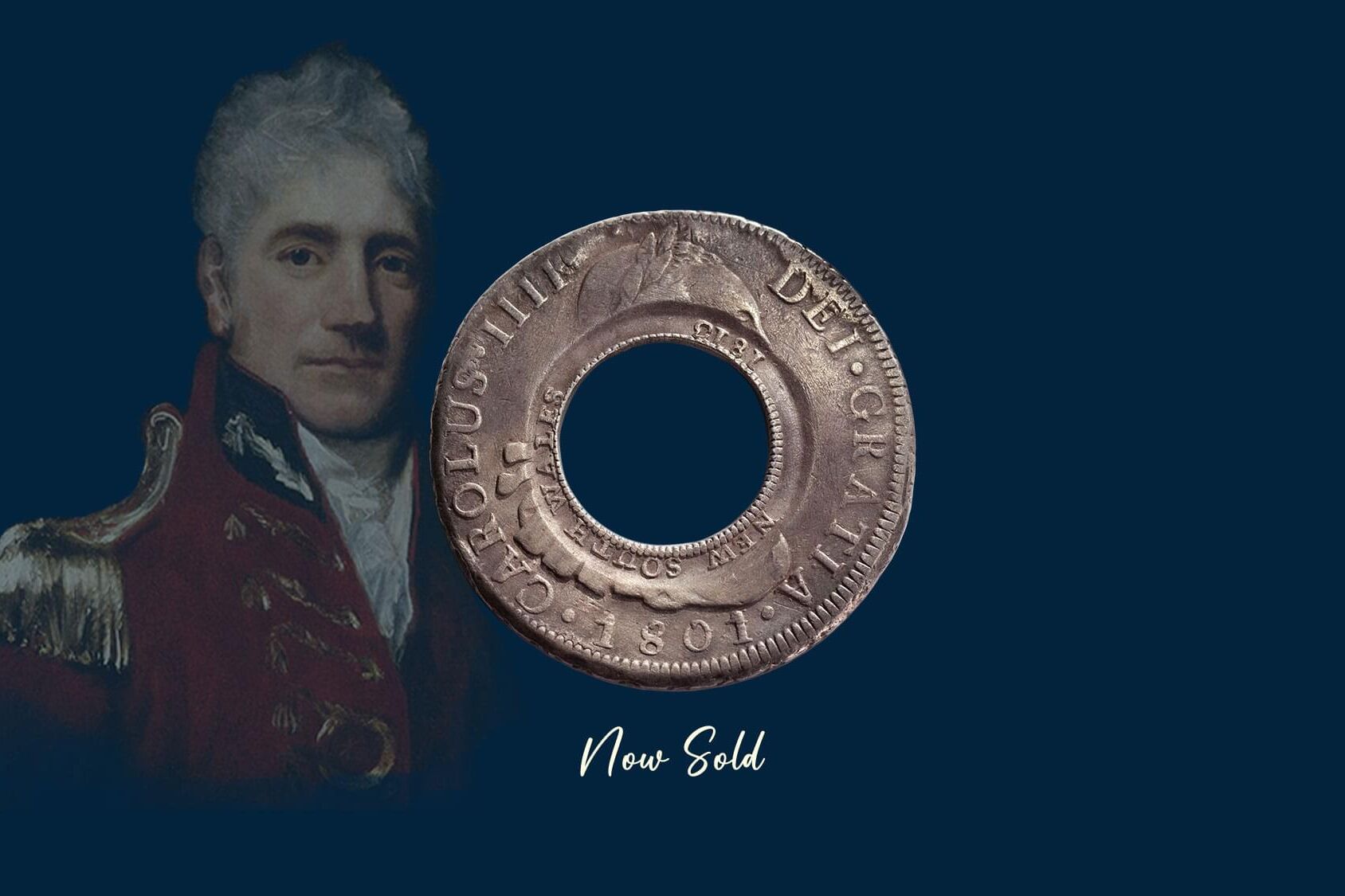

While enormous potential wealth was being dug out of the ground, there was no immediacy in transforming the gold into currency. Coined money was scarce and the colonial governments had no authority to strike currency. That meant gold had to be shipped to London to convert into sovereigns, involving substantial shipping costs and a round-trip time of about six to eight months.

The banks monopolised gold buying on the fields, forcing artificially low prices on the diggers who were powerless to achieve the higher London price. Transport from the fields was dangerous and expensive.

There was unanimous agreement amongst the five colonies, Victoria, Western Australia, Tasmania, South Australia and New South Wales, that a gold coinage had to be locally produced, that the six month turnaround of shipping gold off to London and receiving sovereigns in exchange was unworkable. A more immediate medium of exchange was required to transact commerce. As each colony was under different pressures however, they failed to agree on the form the exchange medium should take. And to its urgency.

In 1851, the New South Wales legislature debated the establishment of an Assay Office and a Mint, the final decision to follow protocols and request Royal approval for a Mint. In 1852, both the colonial Governments of South Australia, under Governor Henry Young, and that of Victoria, under Charles La Trobe, considered the establishment of an Assay Office, the former eventually pursuing the idea and producing the world famous Adelaide Pound.

The Gold Rush created a social and financial crisis to which colonial governments were forced to respond. The Gold Rush also created opportunities for profit, to which private individuals responded, the most noted of whom is William J. Taylor, his name attached to the famous Kangaroo Office Gold Coins.

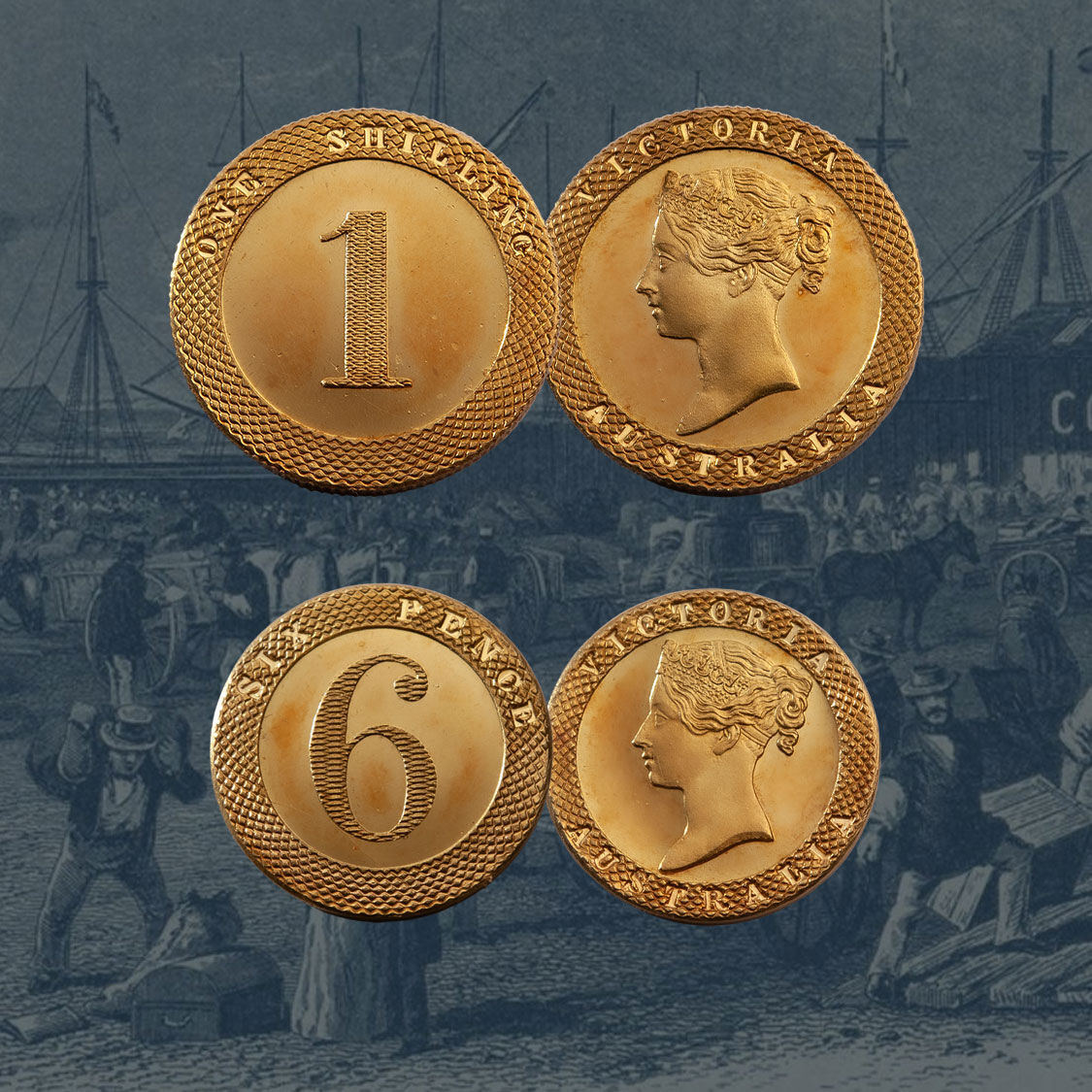

Kangaroo Office Gold Shilling

Kangaroo Office Gold Shilling

Kangaroo Office Gold Sixpence

Kangaroo Office Gold Sixpence

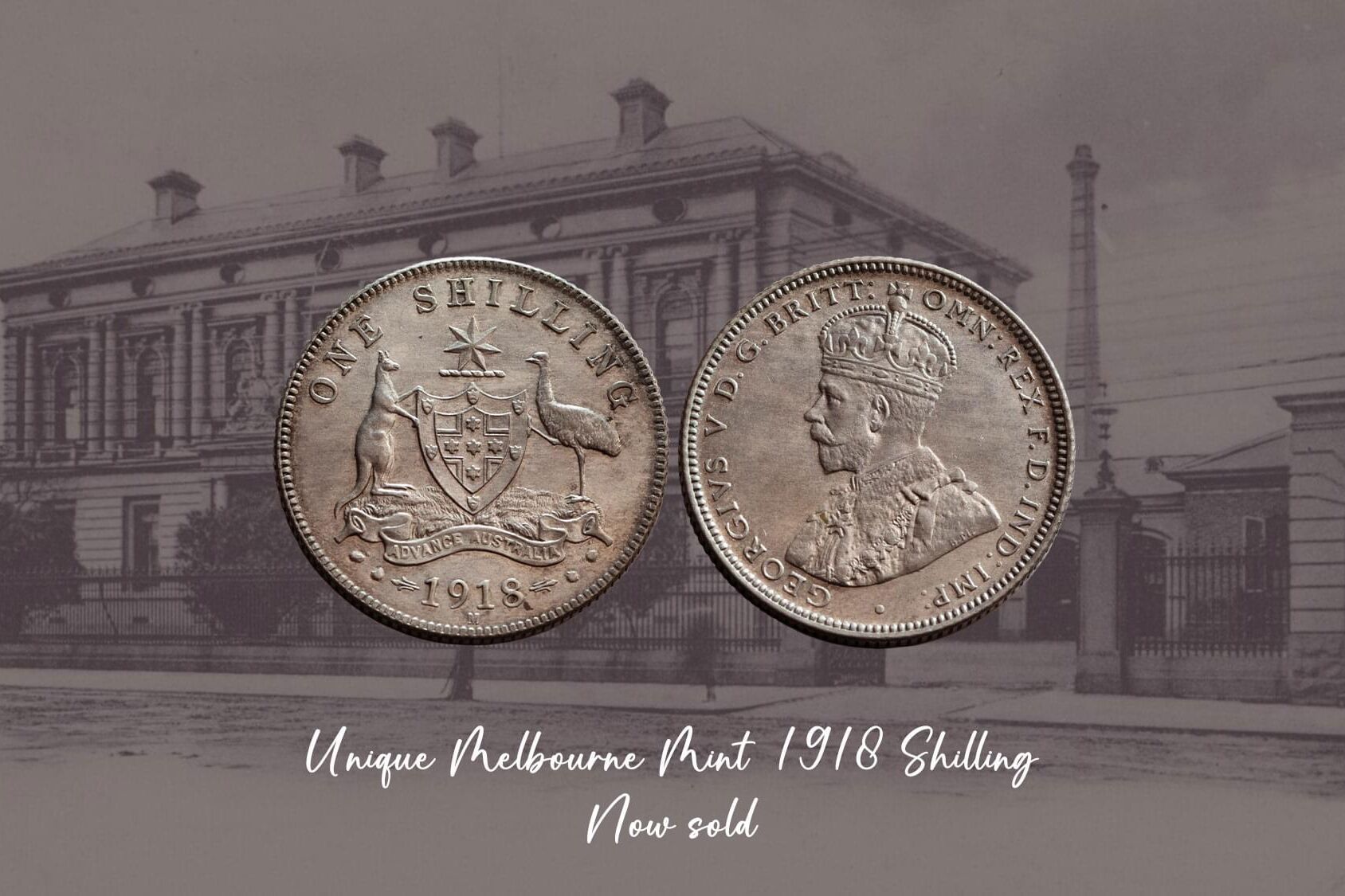

The pathway to an official Australian gold coinage spanned four years, commencing in 1851 with the discovery of gold deposits in New South Wales and Victoria. And finishing in 1855 with the opening of the nation's first mint, the Sydney Mint.

There were several significant events along the way.

In 1852, the South Australian Legislative Council passed the Bullion Act, legislation that facilitated the striking of the nation's first gold coin, the Adelaide Pound. It was a short term measure to provide a medium of exchange, the Act expiring on 28 January 1853. In the same year, the British Government approved the opening of a branch mint of the Royal Mint London in Sydney.

Approval was granted on the basis that the nation's first mint, the Sydney Mint, would be self sufficient and paid for by the colony. And that its sole purpose was to coin gold. Another two years passed before it was opened.

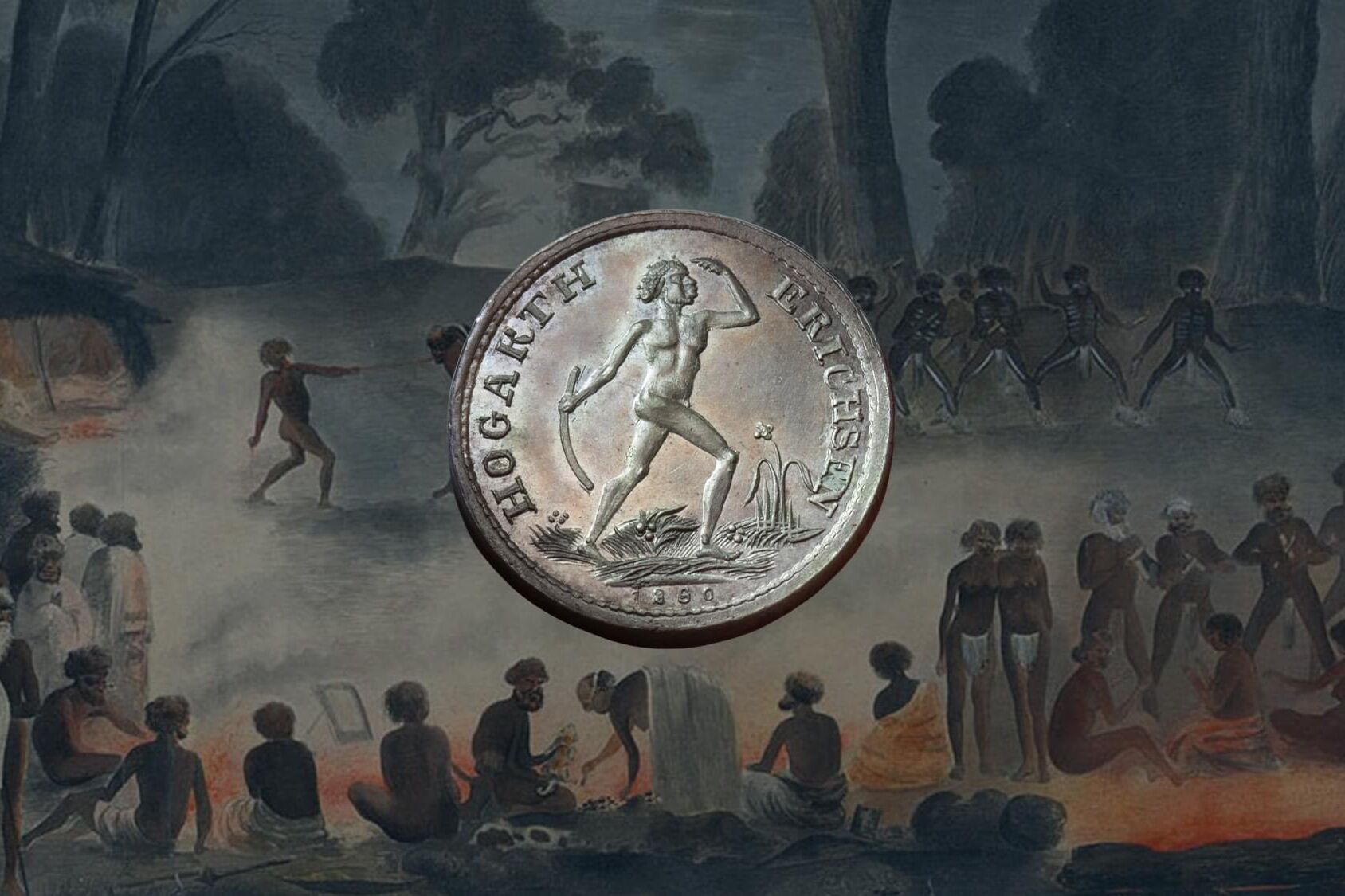

And in 1854, a group of London businessmen opened a private mint in Melbourne, the venture led by engraver and die sinker, William Taylor.

The plan was to take up the strategy of the banks and buy gold on the fields at reduced prices and convert it into a local currency.

The Gold Kangaroo Office Coins are the result of this enterprise.

Soon after the opening of the Adelaide Assay Office in 1852, and the striking of the Adelaide Pound - the nation's first gold coin - there was an attempt to establish a private mint in Melbourne. The mint was called the Kangaroo Office. Its prime goal was to buy gold at cheap prices direct from the fields and convert the precious metal into 'coins' of a fixed weight that would be released at their full value in London.

The plan was devised by English entrepreneur, William Joseph Taylor. By trade Taylor was an engraver and die sinker, active in the numismatic industry producing both coins and medals. He formed a syndicate to finance the operations with two colleagues, Hodgkin and Tyndall. The total investment was £13,000.

Taylor's mint was only one component of a broader-reaching enterprise that was based in London. The overall plan was to profit from all aspects of the Gold Rush and included a clipper ship - called the Kangaroo - that would bring migrants and goods from England to Melbourne and return with gold in its specially outfitted strongroom.

The Kangaroo sailed from London on 26 June 1853. On board, the pre-fabricated structure to house the mint and the shop. And the coining press, dies and two employees, Reginald Scaife, the Manager, and William Morgan Brown, his assistant. The ship arrived at Hobsons Bay, Melbourne on 26 October 1853.

The Kangaroo Office got off to a bad start as there were no facilities at the wharf for off-loading heavy equipment, such as the coining press. With no other option available, the press was dismantled, moved and reassembled, a process that took six months. The Kangaroo Office eventually commenced operations in May 1854, striking gold coins. To thwart currency laws, the designs were made to look more like weights than coins. Taylor himself cut the dies for a 2oz, 1oz, 1/2oz and ¼oz gold piece, each dated 1853.

The coins were exhibited at the Melbourne Exhibition of 1854 (17 October - 12 December) and were written up in the Argus Newspaper as "several tokens of pure Australian gold were exhibited by Mr. Khull, bullion broker. They were manufactured by Mr. Scaiffe and are to be exhibited at our Palace of Industry."(Sadly a price was never quoted.)

Apart from the logistical difficulties of setting up business, the financial viability of the Kangaroo Office came under an immediate cloud. By mid-1854 when the mint became operational the price of gold had moved up to £4/4/- an ounce, vastly different to the £2/15/- per ounce when the plan was hatched. And there was a glut of English sovereigns in circulation.

By the middle of 1854, Reginald Scaiffe, the Kangaroo Office Manager, had an overwhelming sense of failure for the shop had taken less than £1 in trading, he had a ten-year lease, could not find cheap labour. Nor cheap gold. And basically had no customers.

Despite the financial challenges of the operation Taylor was unconvinced that his days as a coin designer and manufacturer were at an end. In 1855 he produced dies for the striking of a sixpence and shilling in gold, silver and copper. This was his first attempt at producing a piece depicting a value rather than a weight. The coins were struck with a milled and plain edge, the former believed minted circa 1855, the latter circa 1860.

The sixpence and shilling featured the same broad engine-turned rim as the earlier minted gold coins. The obverse however featured a superb portrait of Queen Victoria with VICTORIA and AUSTRALIA embedded in the rim. The reverse featured the denomination in figures at the centre and in letters embedded in the rim above.

Taylor operated his Kangaroo Office for three years during which time he sustained substantial losses. With all hope of a profit gone, the dispirited promoters in London issued instructions for the Kangaroo Office to be closed. Now while it is true that Taylor never achieved his ambitions, the Kangaroo Office coins are revered by collectors right across the globe.

Shown above the obverse and reverse of the Kangaroo Office Gold Shilling Circa 1855

Shown above the obverse and reverse of the Kangaroo Office Gold Sixpence Circa 1860

Highlights of Coinworks Inventory

© Copyright: Coinworks