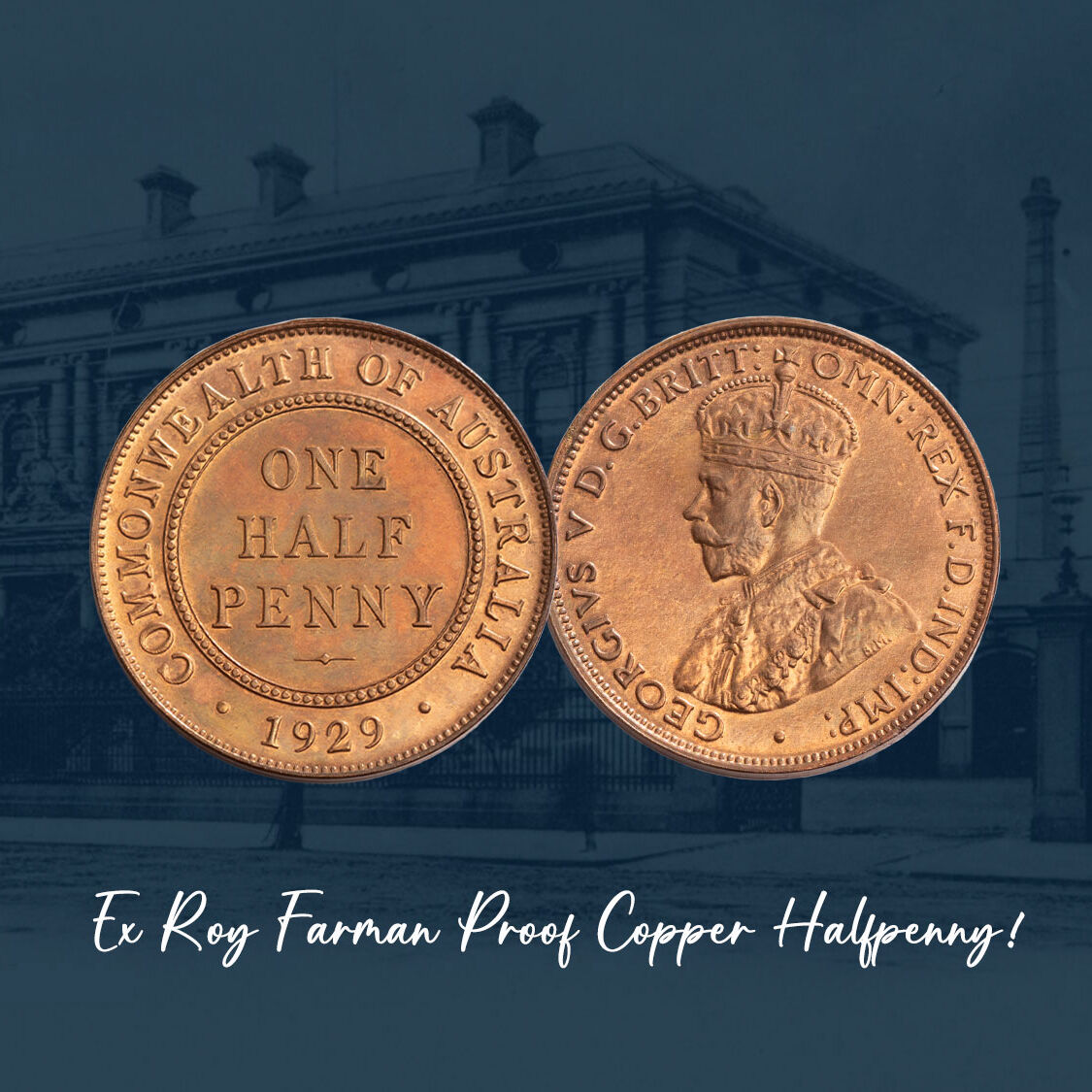

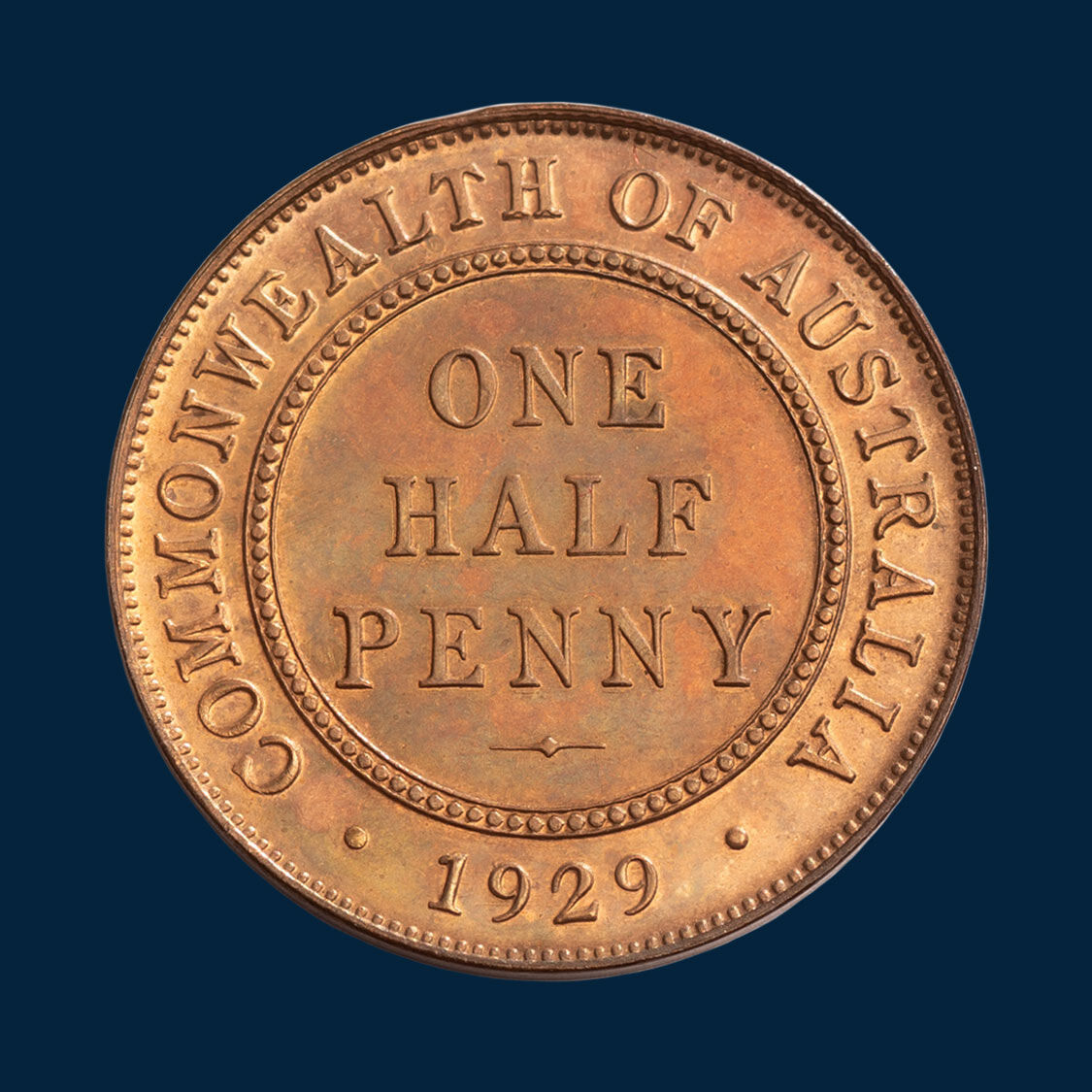

Click here for more details on this Product

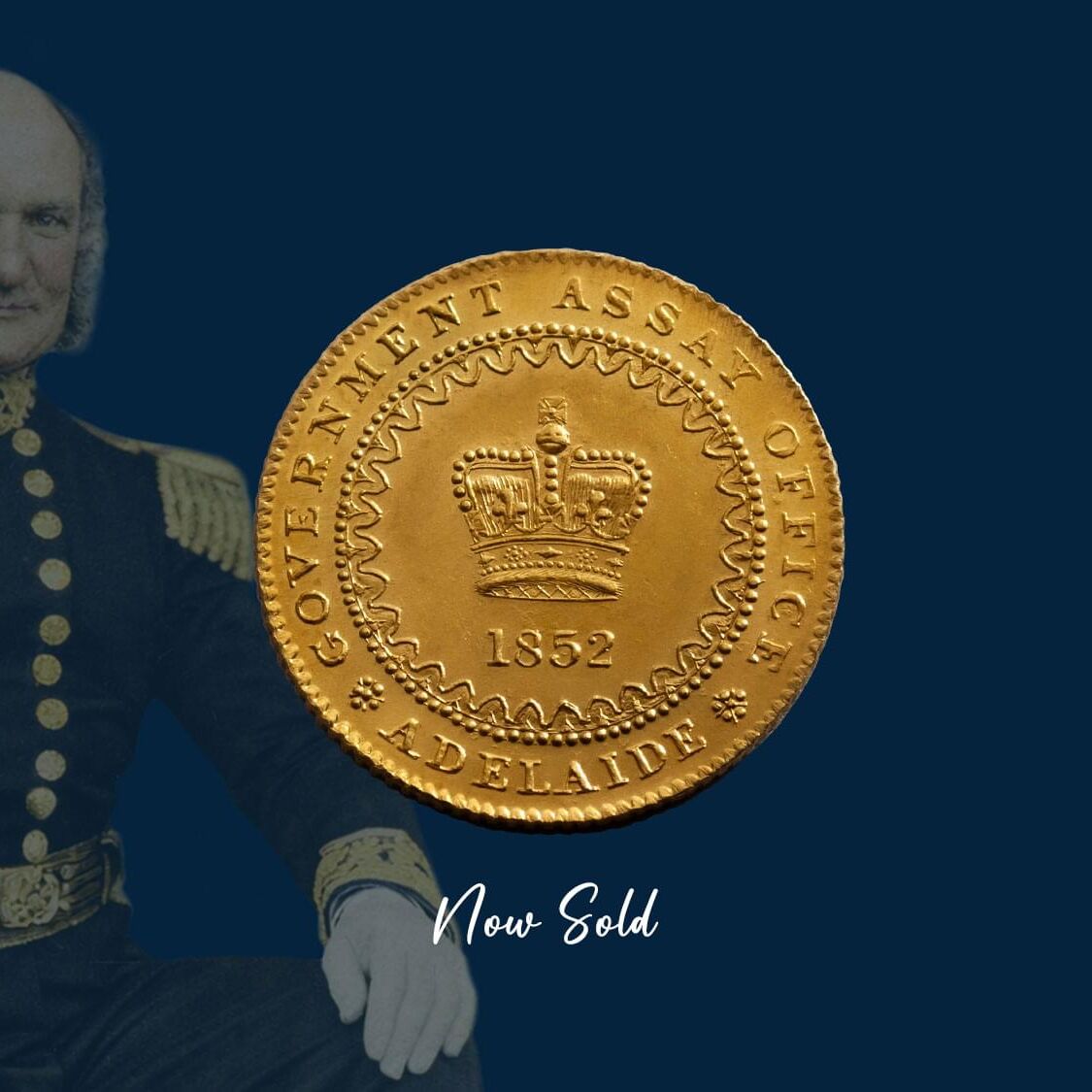

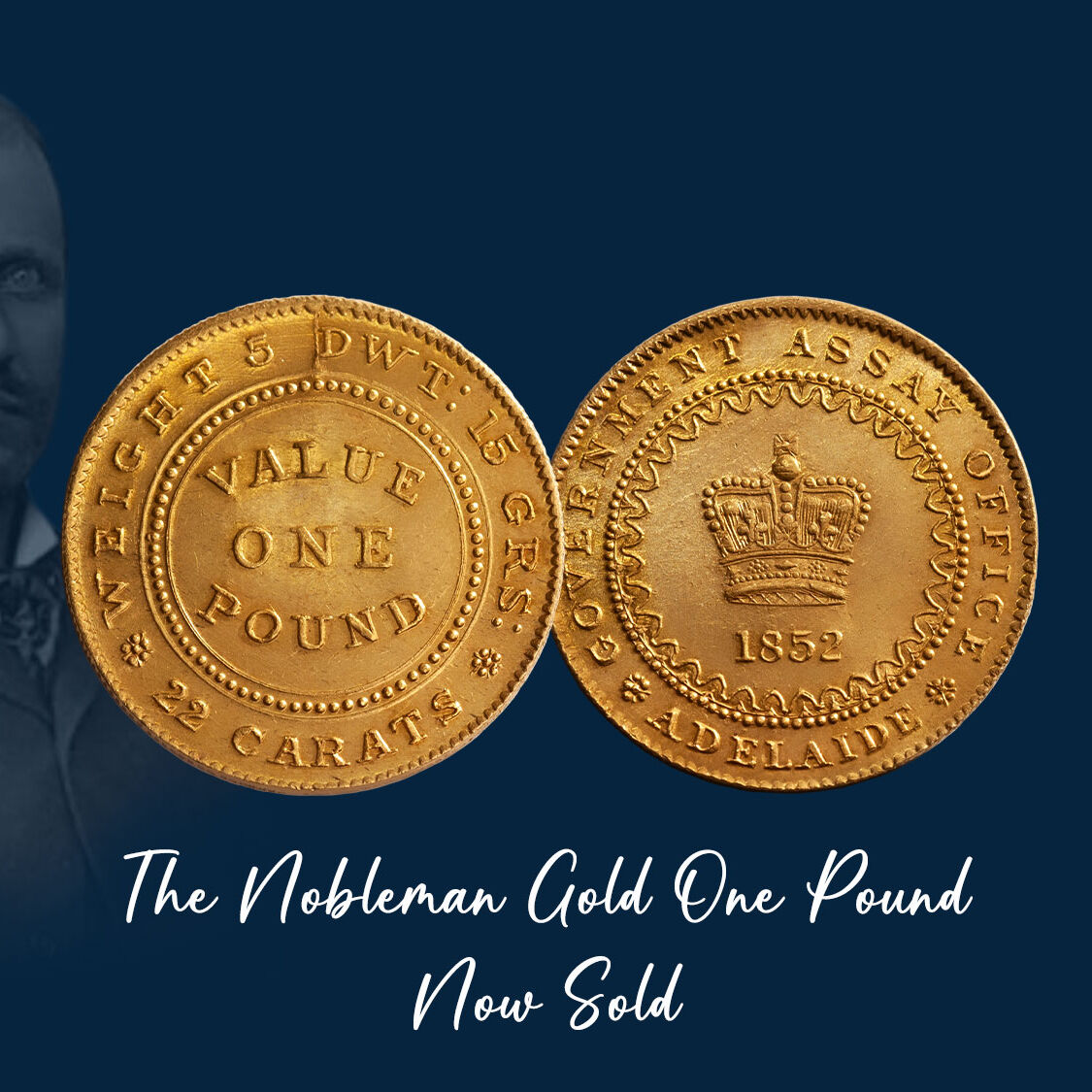

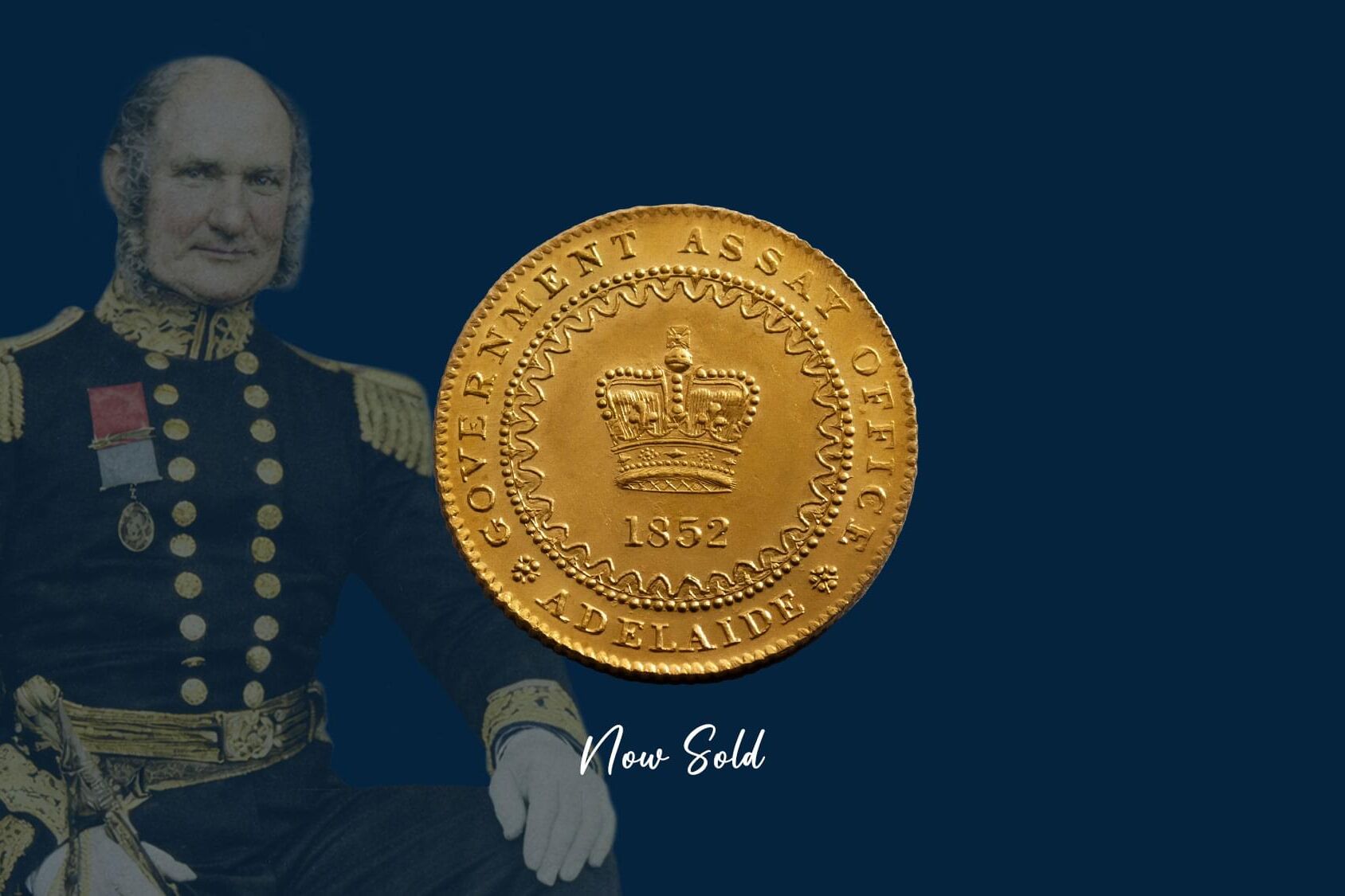

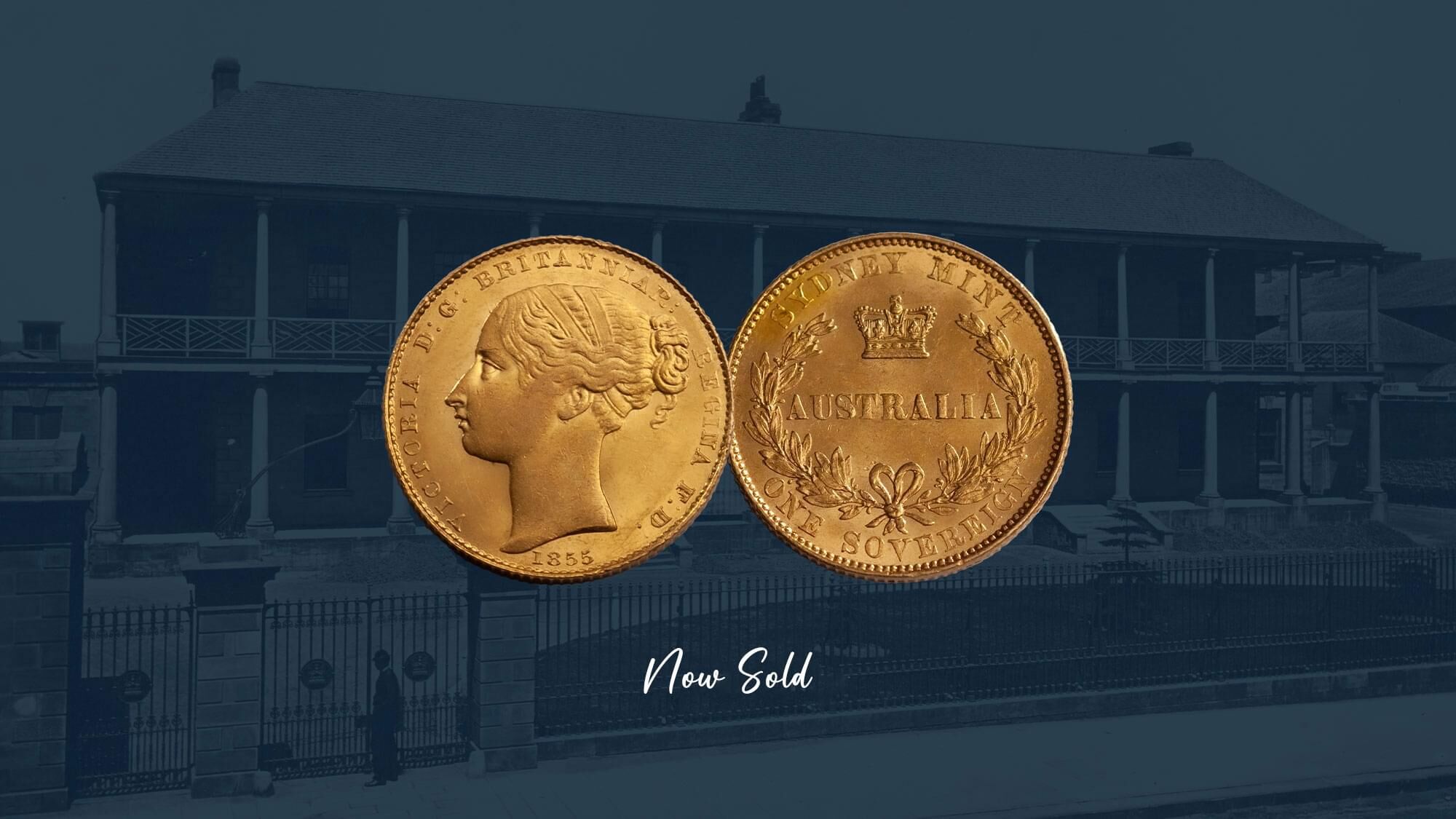

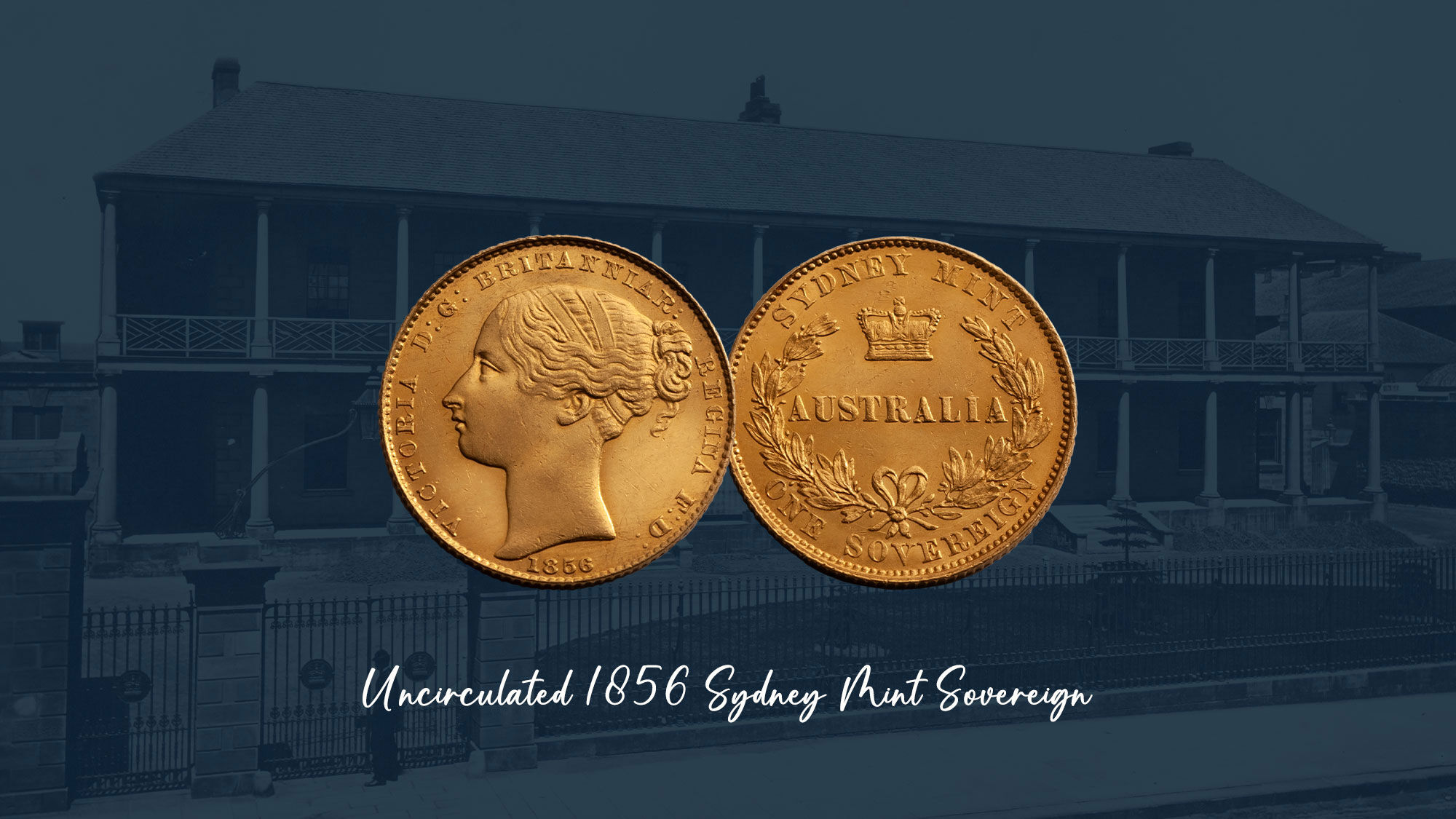

The Adelaide One Pound is the nation’s first gold coin, struck in 1852 at the South Australian Government Assay Office, Adelaide.

Local jeweler and engraver Joshua Payne created the dies for the nation's first gold coins.

The obverse declared the issuing authority, Government Assay Office Adelaide, encircling a crown and the date, 1852, the design used continuously throughout production. The reverse declared the fineness and weight encircling it's value.

With its fine design detail, the Adelaide Pound is compelling and a piece of significance, its status as the nation's first gold coin ensuring that it will never be forgotten.

And it is extremely rare with less than forty examples surviving from the first production run and perhaps two hundred and fifty from the second.

Either first or second run, the Adelaide Pound is a prized possession, an iconic gold coin revered by local and international buyers.

1852 Adelaide Pound Type II

1852 Adelaide Pound Type II

History records that disaster struck during the early stages of the minting of the 1852 Adelaide Pound. Die-maker and engraver Joshua Payne later confirmed that staff had struggled to find the correct pressure levels to exert on the dies to execute a strong overall design.

In the early stages of production, pressure was applied to the edges to ensure that the denticles and legend were strong. The downside to this decision is that excessive pressure applied to the edges cracked the reverse die, forcing an interruption to minting. The upside to this decision is that Adelaide Pounds struck during the first production run have almost picture-perfect edges and beautiful strong denticles.

Relaxing the pressure on the dies in the second production run, lengthened the die usage but created its own shortcomings. Once the pressure was reduced on the edges, the perfection that was achieved in the denticles and legend in the first run of coins was simply not achievable in the second run.

Adelaide Pounds from the second production run notoriously have weakness in the edges and weakness in the legend, most particularly in the Assay Office area. And this is noted in about nine out of every ten examples. But, the crown design will invariably be well executed with flattened areas mainly due to circulation. (Flattened areas may also reflect die usage and be due to a poor strike.)

Supremely fine detail in the crown.

Strength in the legend and edge.

This Type II 1852 Adelaide Pound has a beautiful balance of strong edge denticles, strong legend and a brilliantly struck crown. (See above.) It is the exception to those most frequently sighted and was formerly held by the owner of the famous Nobleman 1852 Adelaide Pound Type I.

Choice Uncirculated 1852 Adelaide Pound struck using the second reverse die featuring a scalloped inner border (Type II)

Price: $75,000

This 1852 Adelaide Pound is ascribed the higher quality ranking of Choice Uncirculated and is one of the best examples of the nation’s first gold coin.

The addition of the word ‘choice’ takes a coin to a quality level rarely seen when discussing circulating currency and one of the highest quality rankings available in numismatics.

To warrant that grading the coin has to be brilliantly preserved with lots of eye appeal. And the strike has to be powerful.

This Adelaide Pound has both.

The coin retains its original brilliance and is highly lustrous. The reverse in particular is magnificent. And the design has been brilliantly executed, the edges strong all the way around and the legend well defined, again all the way around (notorious areas of weakness in most Type II Adelaide Pounds). The crown has supremely-fine detail.

The Adelaide Pound is a coin that will always be in favour. It is ‘gold’ after all, one of our most popular collecting metals. The coin appeals to all age-groups, including the younger generation, and that augurs well for its future.

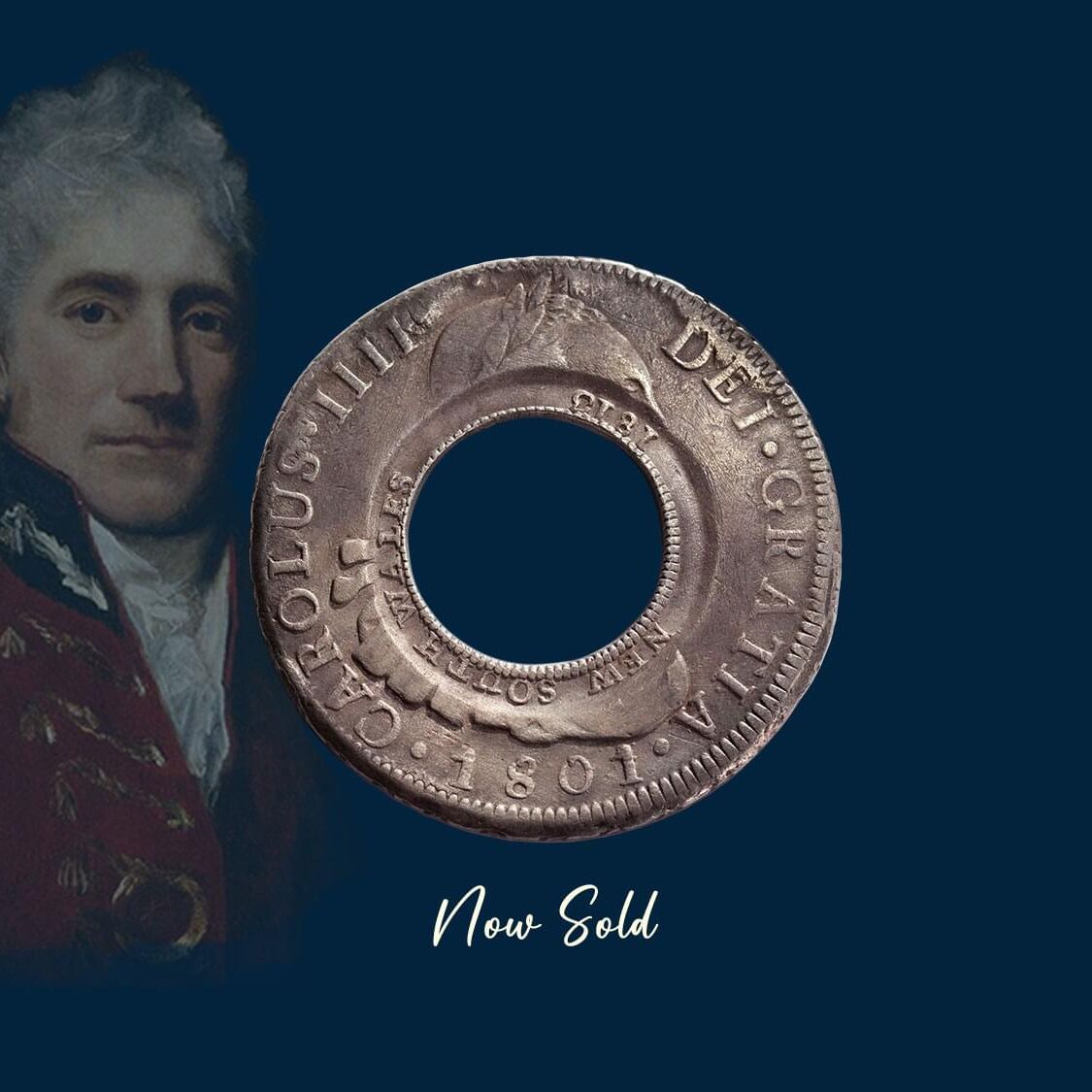

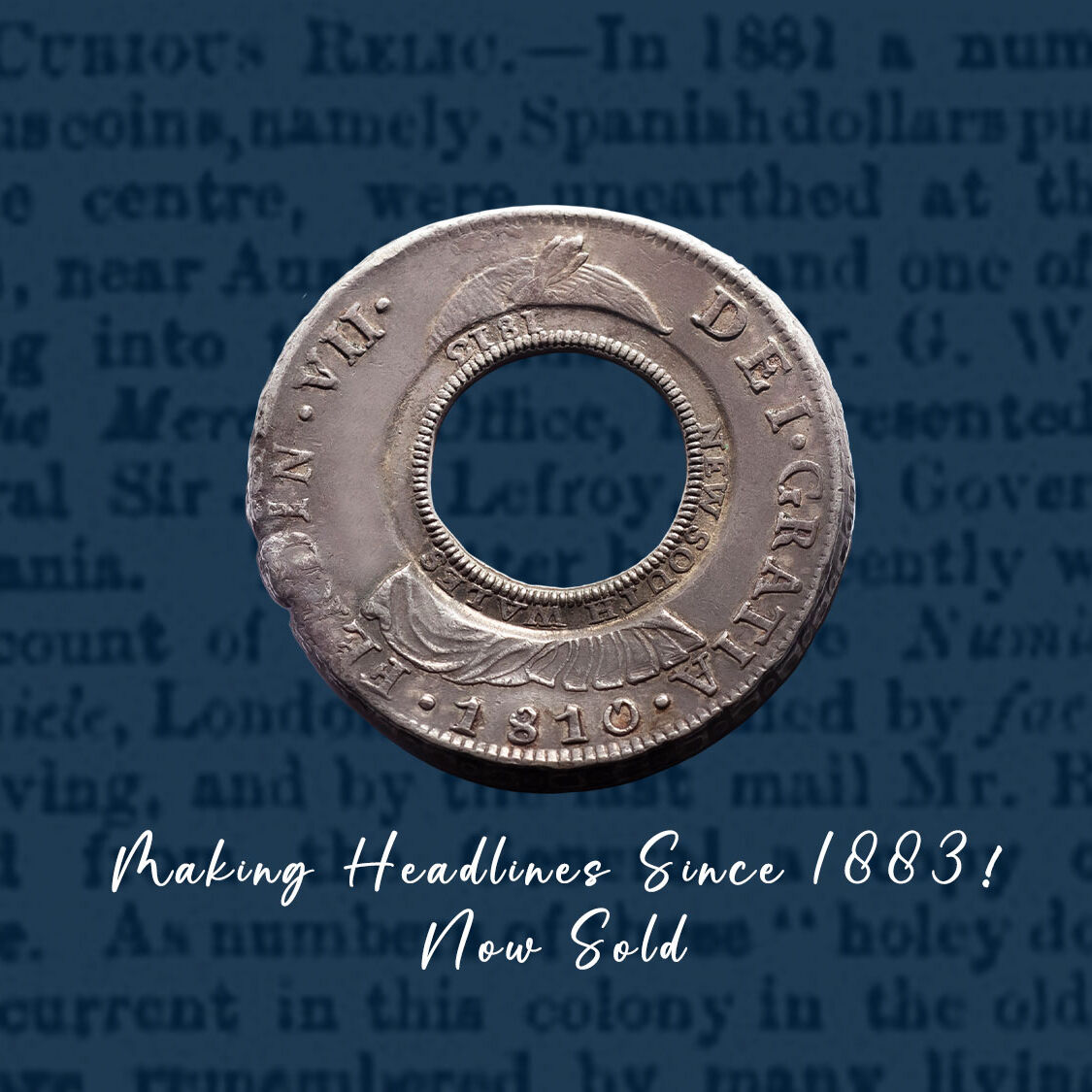

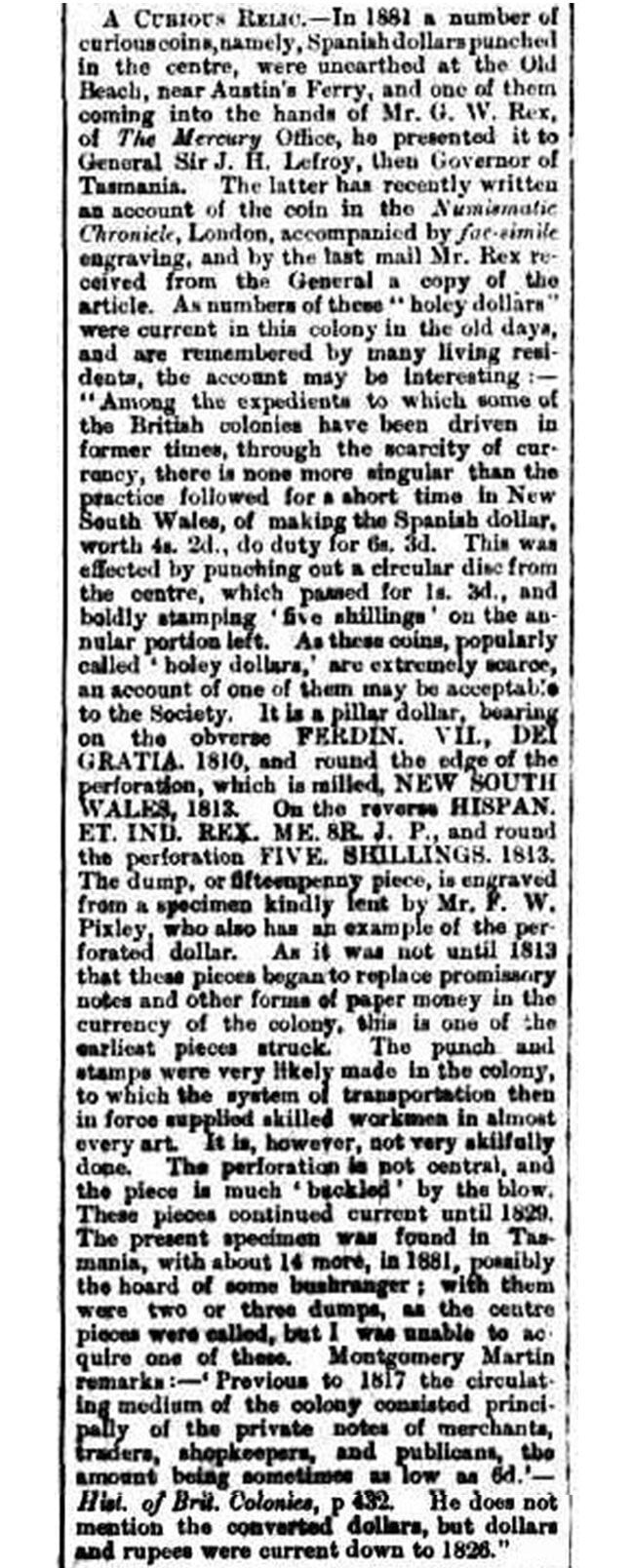

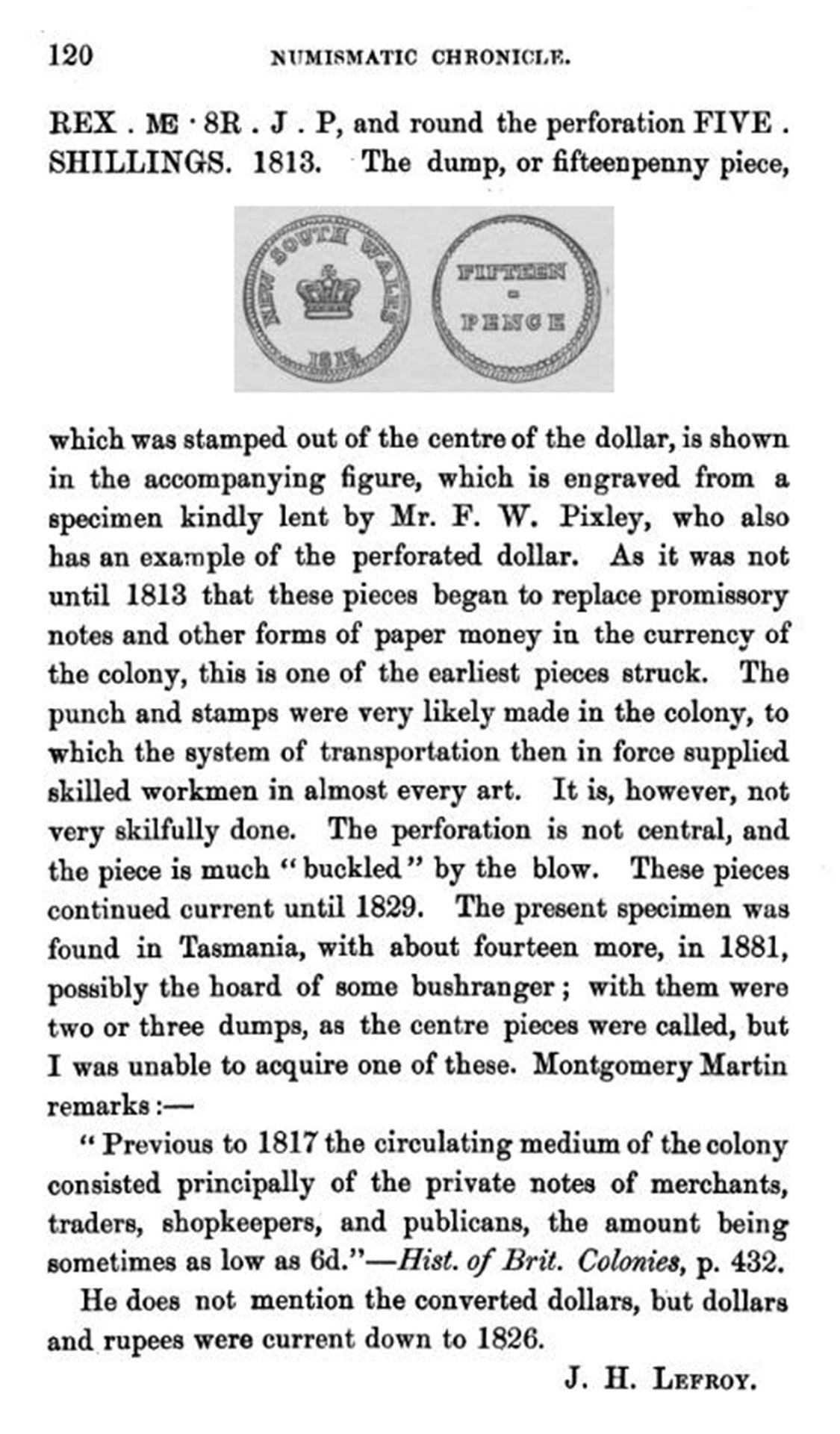

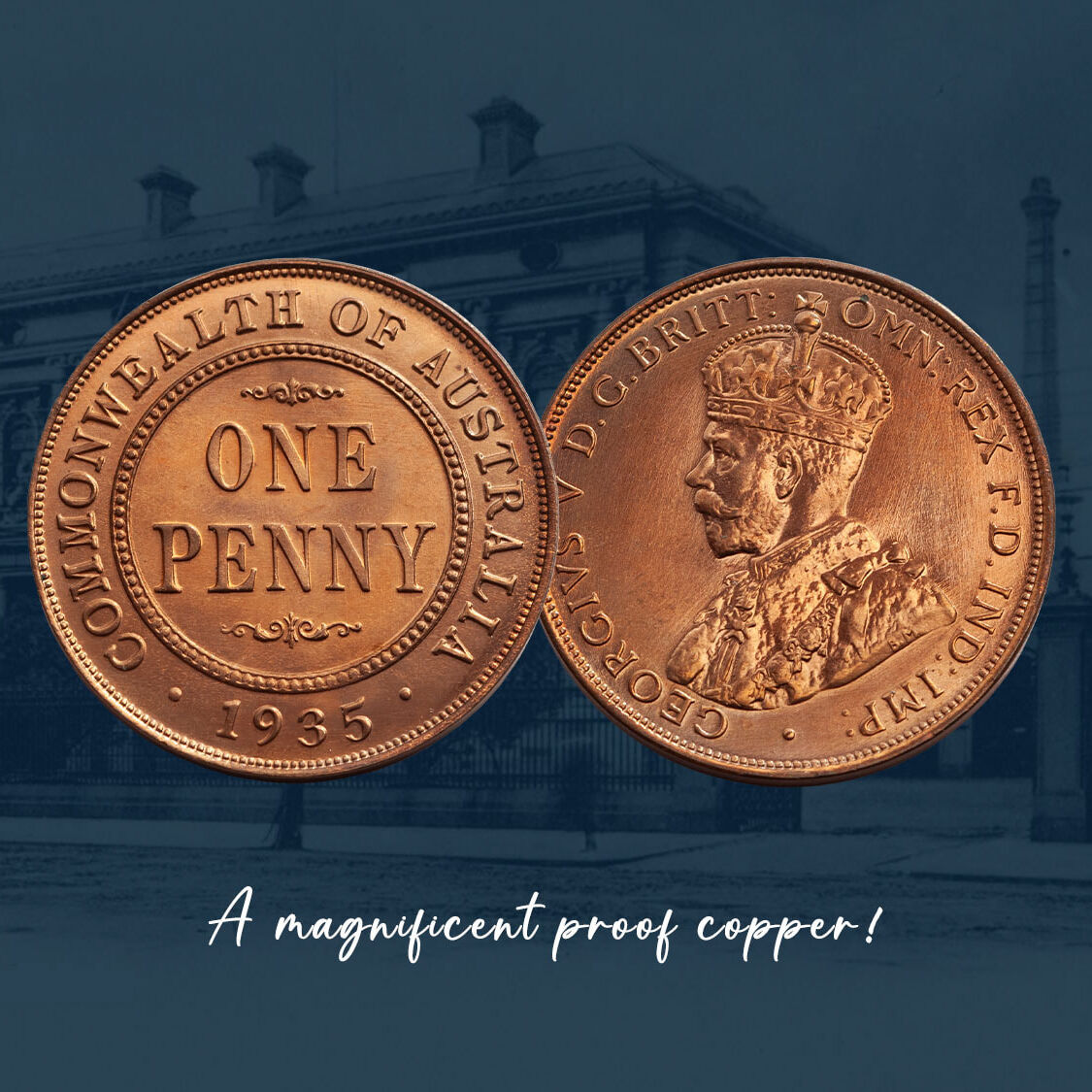

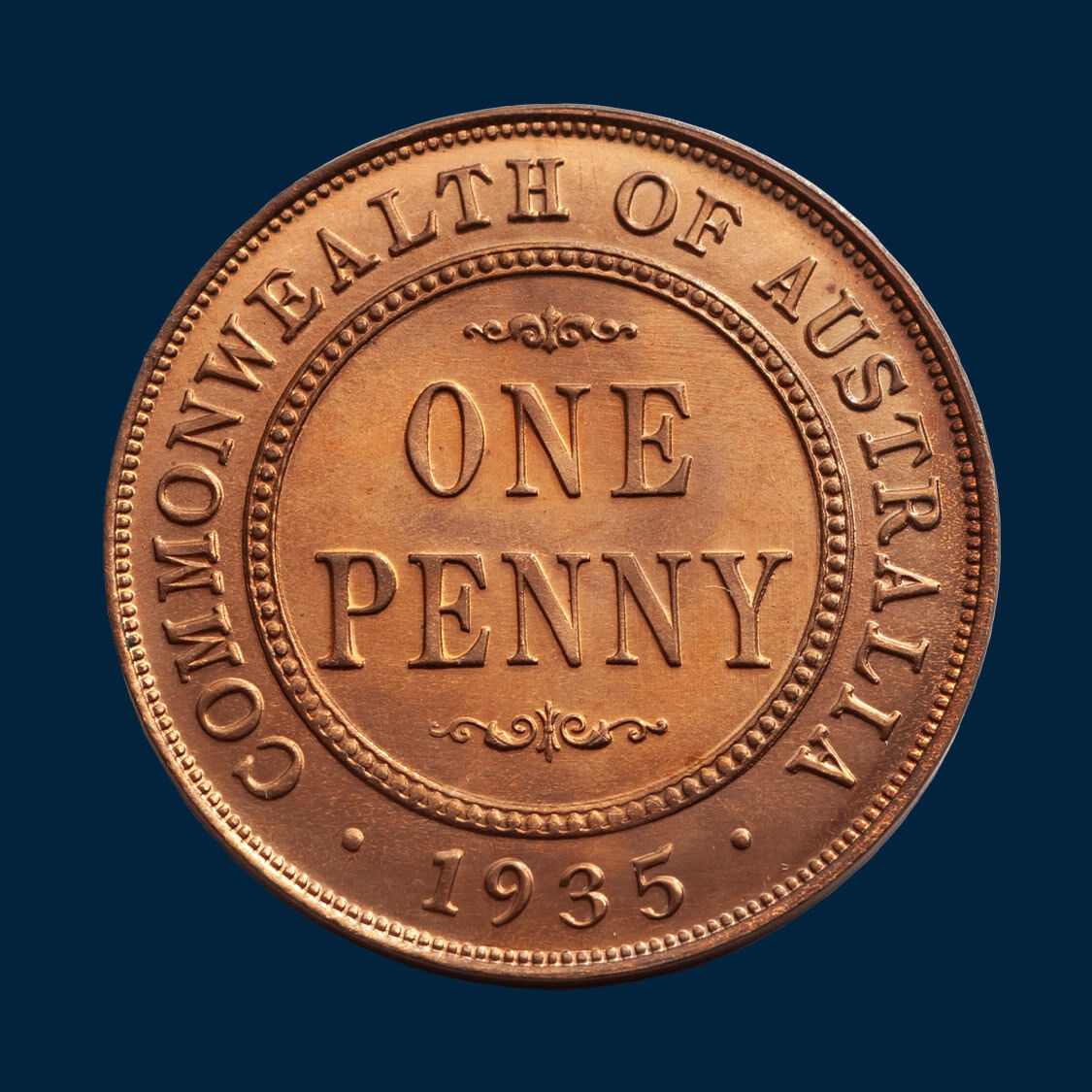

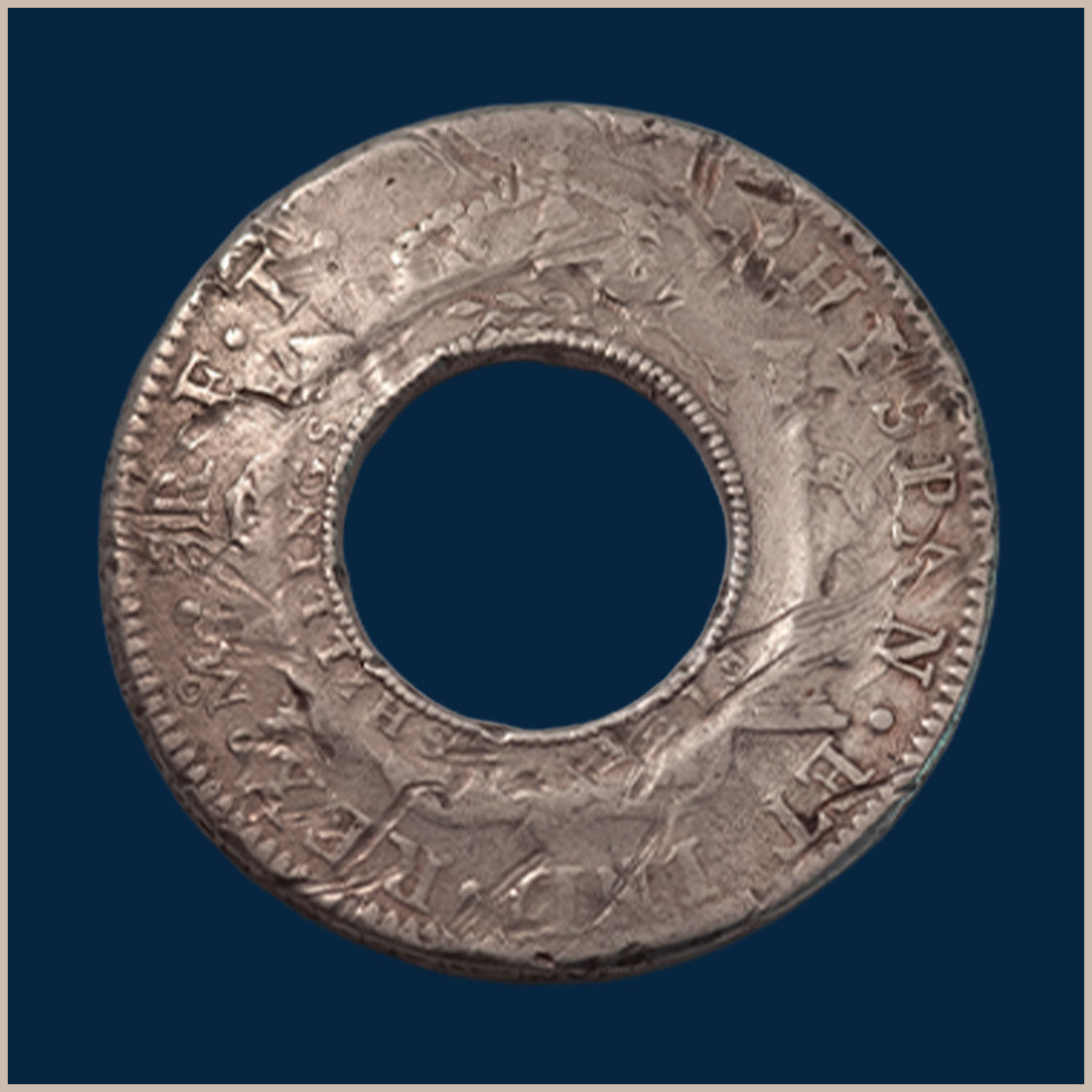

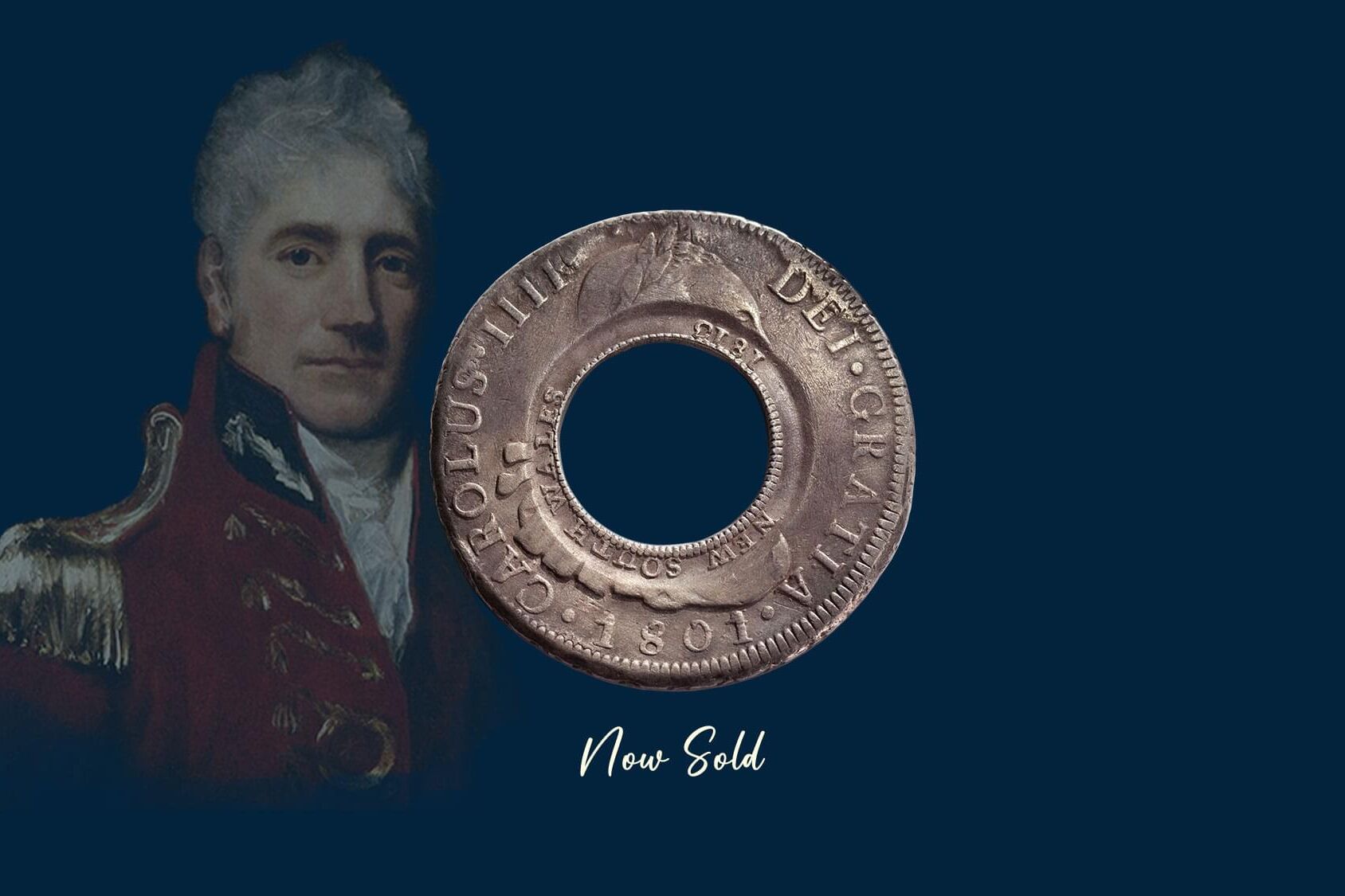

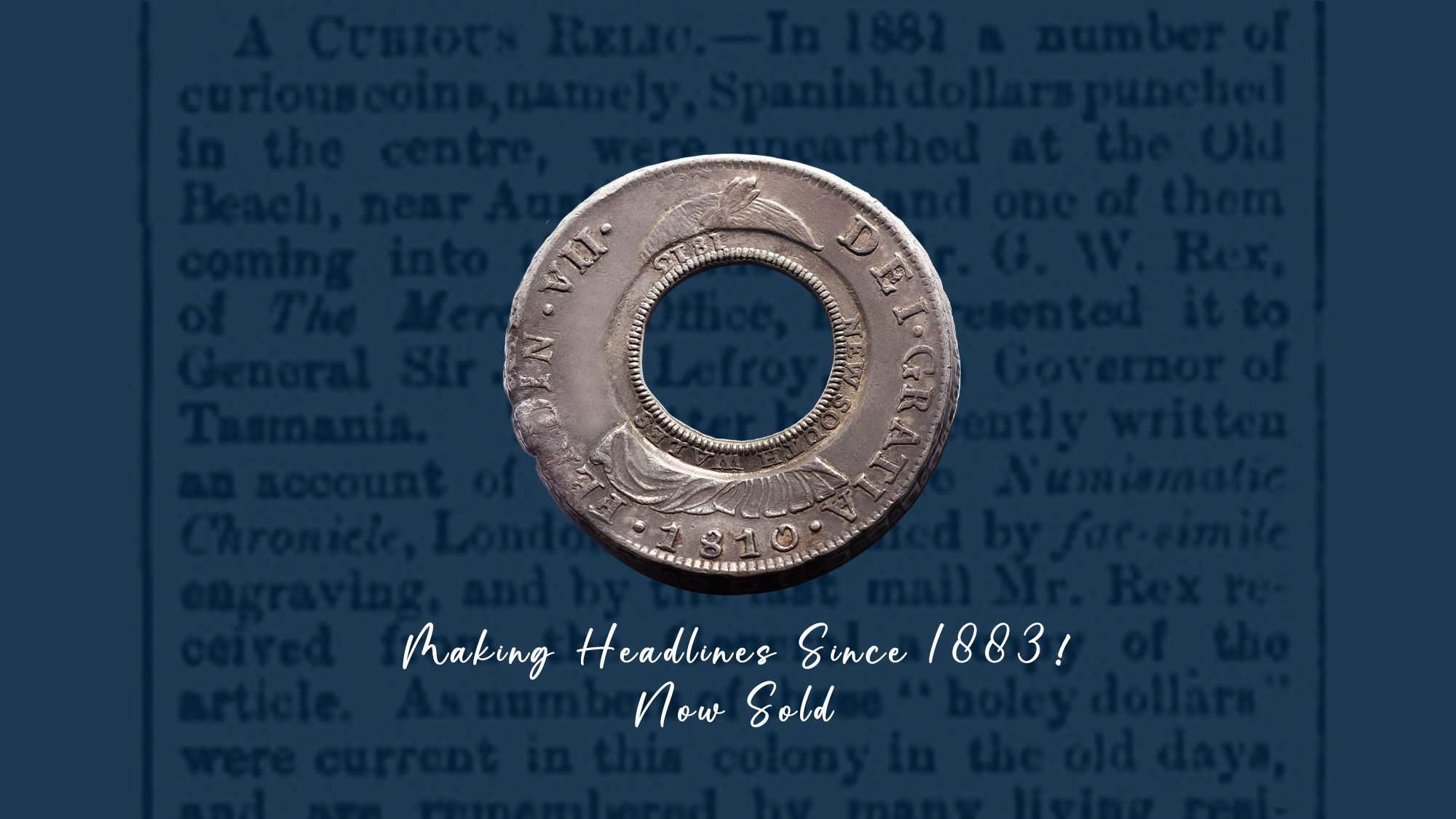

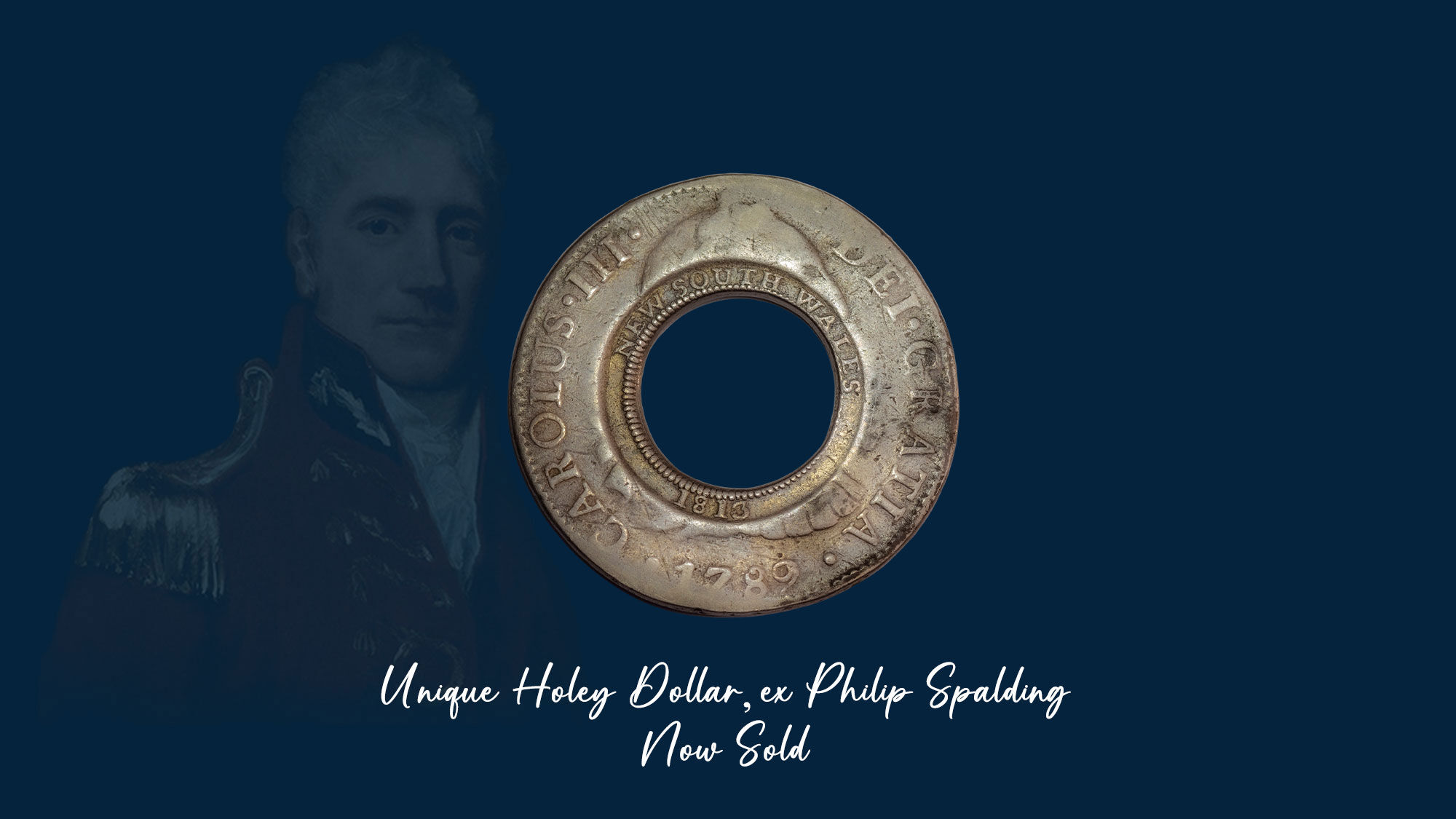

This 1813 Holey Dollar was created from a silver dollar that was minted at the Potosi Mint in Bolivia. 'Potosi' makes it a big deal! This is a mint that is very rarely seen.

Of the two hundred Holey Dollars available to collectors, only fifteen were converted from silver dollars struck at the Potosi Mint in Bolivia. And if you look closely at the fifteen, only five are known in the upper quality levels, of which this coin is one. (By comparison almost one hundred and fifty were created from silver dollars produced at the Mexico Mint, located in the silver-rich colony of Mexico.)

This Holey Dollar is high quality. And this Holey Dollar is extremely rare. Offered in Amsterdam in 1910, it is yet another top Holey Dollar that has returned to its country of origin from Europe over the last century.

Click here for more details on this Product

A Holey Dollar that is extremely rare quality-wise.

Macquarie's order for Spanish Silver Dollars was fulfilled by the East India Company in Madras, and was not date specific or quality specific. Macquarie simply wanted coins.

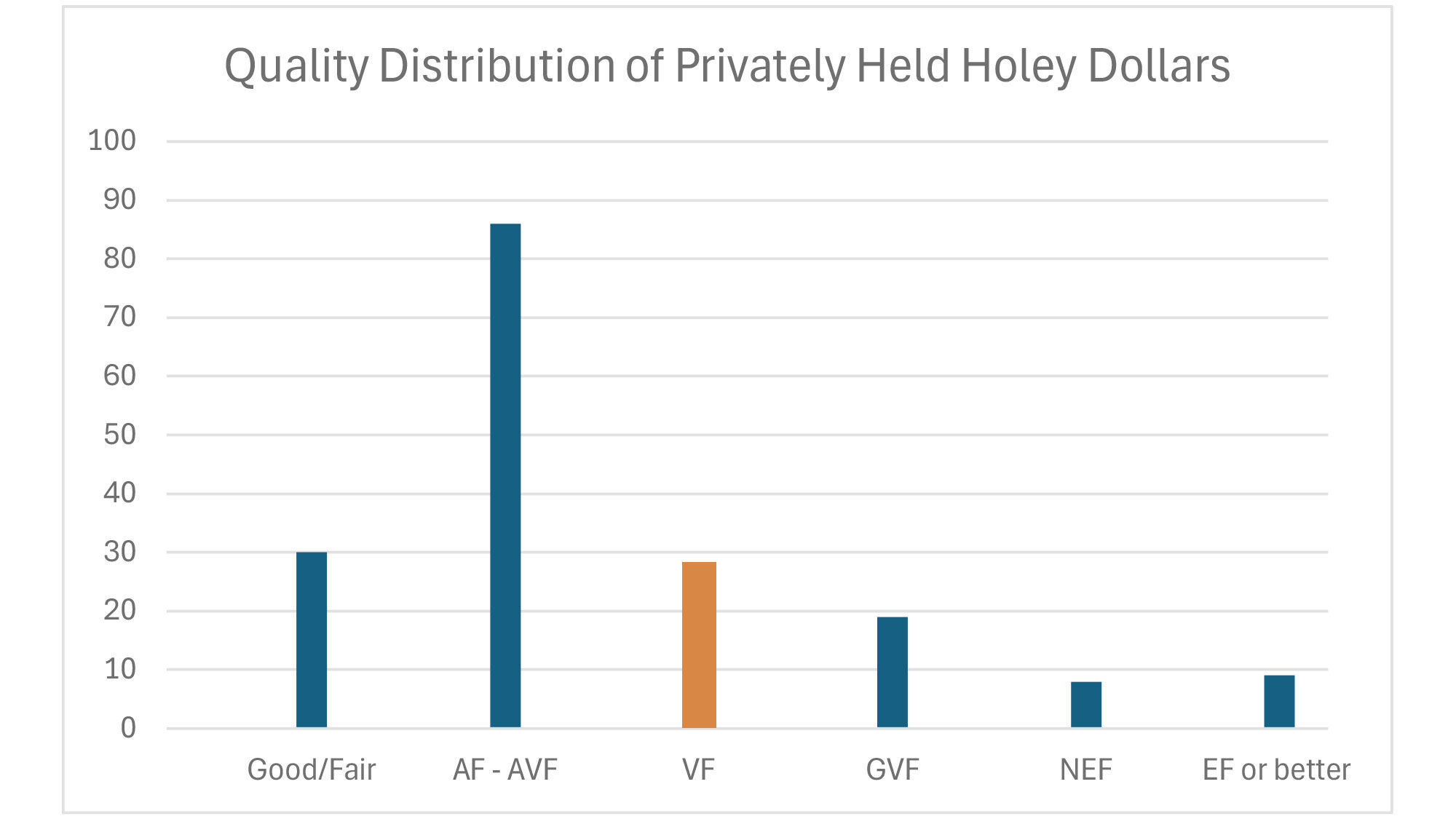

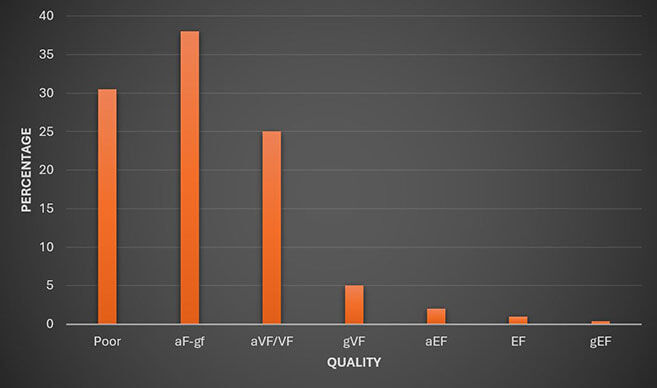

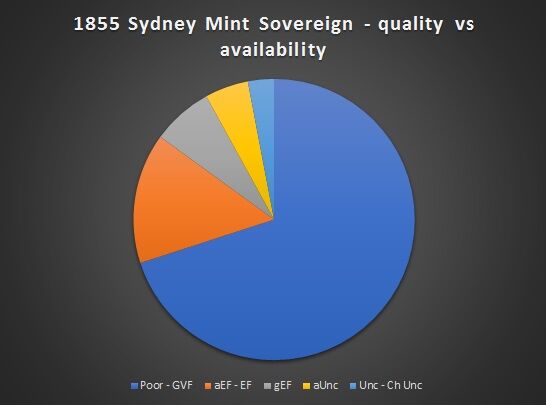

An analysis of surviving examples confirms that the majority of Holey Dollars are well worn. The analysis also confirms that a Holey Dollar at Very Fine is a well above average example (refer chart).

We like the price point at which this Holey Dollar is offered. In our view, the range of $100,000 to $200,000 offers excellent value for your investment dollars.

At this price level, a Holey Dollar will look good to the naked eye, relatively untouched. And the major design detail will still be relatively sharp.

We particularly notice with this coin, there are no harsh knocks, gouges or weaknesses in the metal (which so often occurred when Henshall hammered out the hole).

Good/Fair • Akin to a washer

AF - AVF • About Fine to About Very Fine

VF • Very Fine

GVF • Good Very Fine

NEF • Nearly Extremely Fine

EF or better • Extremely Fine to Uncirculated

Quality of silver dollar: Very Fine

Quality counter stamps: Good Very Fine

Counter stamp dies: II/4: B/4

Potosi Mint, identified by the PTS monogram in the legend on the reverse said to be the inspiration of the '$' sign

The defining quality of this Holey Dollar is that it was created from a Spanish Silver Dollar that was struck at the Potosi Mint. The Potosi Mint being the key here.

Macquarie's order for Spanish Silver Dollars was fulfilled by the East India Company in Madras, and was not date or quality specific. No did he care which mint they came from. The dollars were sourced from various mints around the world, each with a different identifying mark. The percentage of Holey Dollars converted from the mints in Mexico, Lima, Potosi and Madrid are noted here.

• Holey Dollars converted from Mexico Mint dollars - 81 per cent

• Holey Dollars converted from Lima Mint dollars - 10 per cent

• Holey Dollars converted from Potosi Mint dollars - 8 per cent.

• Holey Dollars converted from Madrid Mint dollars - 1 per cent

1813 Holey Dollar created from a Spanish Silver Dollar that had been struck at the Potosi Mint, Bolivia, in 1801 (Mira/Noble 1801/5, Spalding 99).

Price: $165,000

Design type: 5 (Charles IV legend and portrait)

Date of the silver dollar: 1801

Reigning monarch: Charles IV (1788 - 1808)

Portrait: Charles IV

Legend: Carolus (Charles) IIII

Mint and mint mark: Potosi Mint, identified by the PTS monogram in the legend on the reverse said to be the inspiration of the '$' sign.

Quality of silver dollar: Very Fine

Quality counter stamps: Good Very Fine

Counter stamp dies: II/4: B/4

More information on the 1813 Holey Dollar

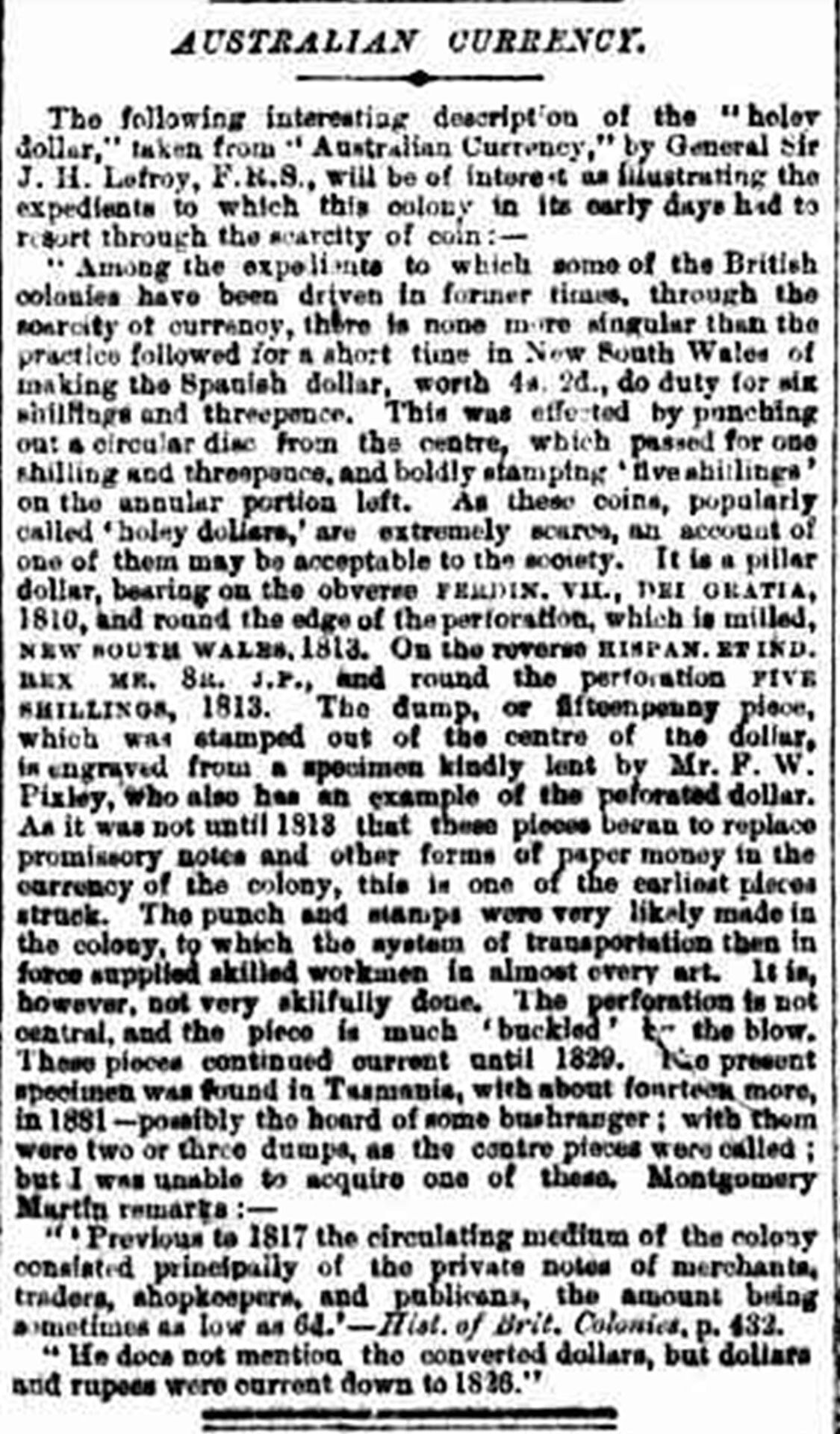

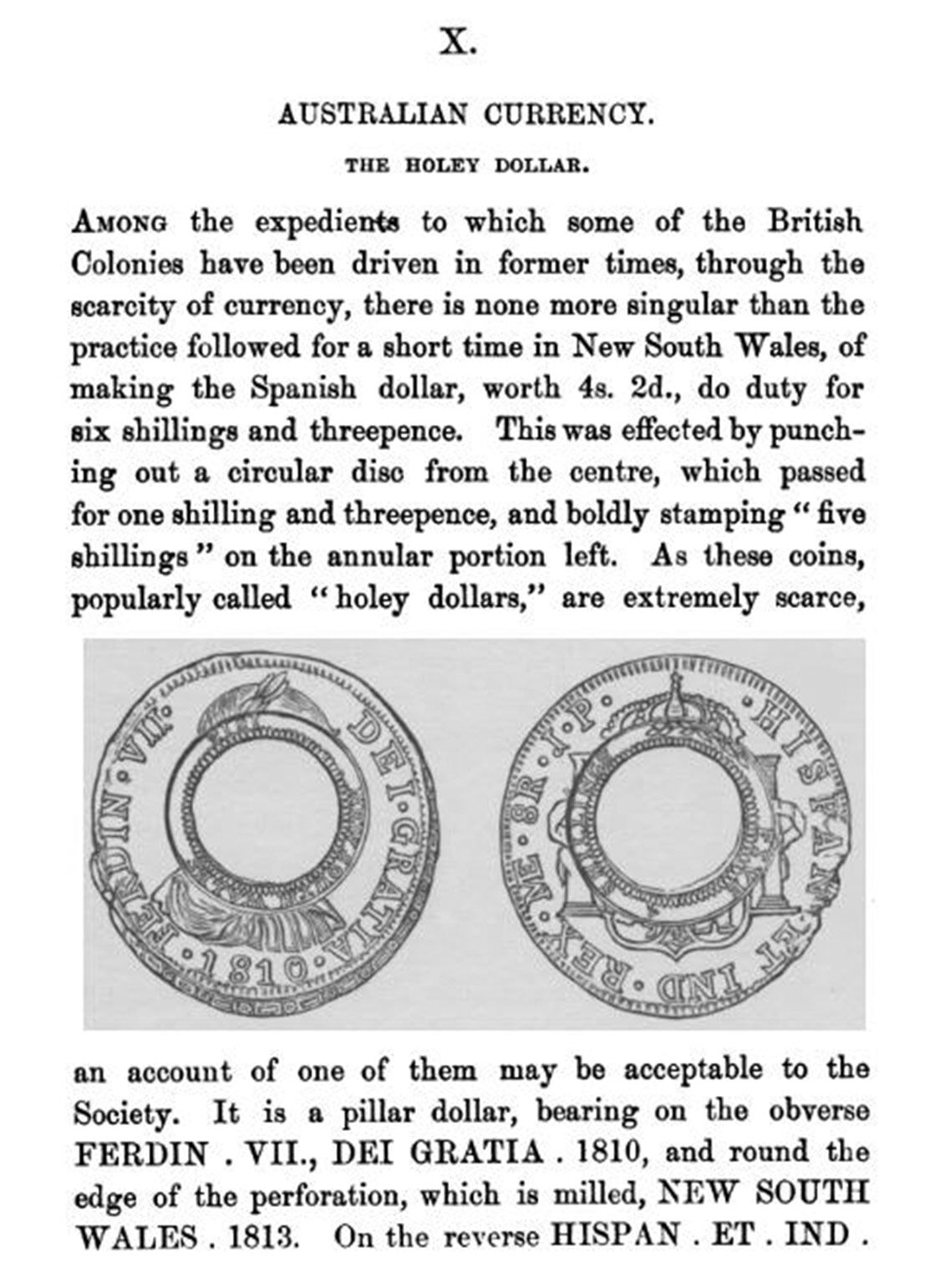

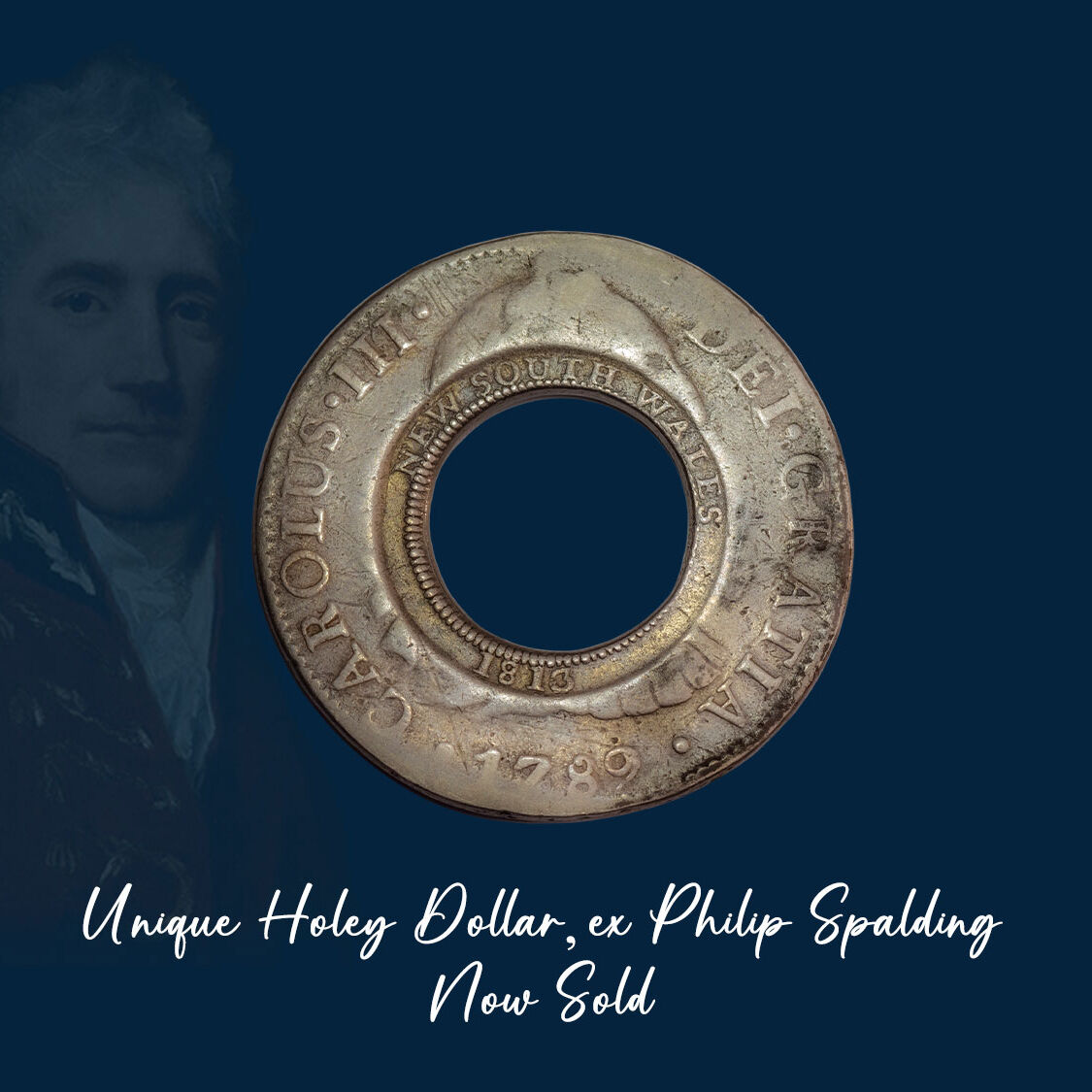

The Holey Dollar is the nation’s first coin, minted in 1813 by order of Governor Lachlan Macquarie. As Macquarie had no access to metal blanks to create his currency, he improvised and acquired 40,000 Spanish Silver Dollars as a substitute.

To make his new coinage unique to the colony, he employed emancipated convict William Henshall to cut a hole in each Spanish dollar. Each holed dollar was then over-stamped on both sides around the edge of the hole. On one side, the date 1813 and the issuing authority of New South Wales. And the other, the value of Five Shillings.

If you look at the entire process, the application of the counter stamps - the issuing authority of New South Wales, the date 1813 and the value of five shillings - is the point at which the 1813 Holey Dollar is created. Prior to that, it was just a Spanish dollar with a hole in it!

The 40,000 Spanish Silver Dollars came with different dates and different design details that reflected the reigning Spanish monarch. And they were sourced from various mints around the world, each mint with a different identifying mark. As the Spanish Dollar was an internationally traded coin, most of them came to Macquarie well used. (We know that because the majority of Holey Dollars are well worn.)

As the Holey Dollar was crafted from a Spanish Silver Dollar (and not a metal blank), assessing its value gives consideration to the original dollar. Its quality. And its rarity, for some are indeed rarer than others.

Consideration must also be given to the extent of circulation once the dollar was converted to an 1813 Holey Dollar by looking at the wear to the counterstamps.

Valuing a Holey Dollar is therefore a multi-faceted process that takes into account seven elements. The date, the monarch and the legend of the original silver dollar. The mint at which the dollar was issued. The quality of that dollar. Now we turn to the counter stamps applied by Henshall. Are they random or precise? And are they worn?

The brief summary above is intended to explain how and why vast price differences can occur with Holey Dollars.

Owning a Holey Dollar is about indulging in an experience, a fusion of history and prestige. And its about savouring the moment.

It has been the inspiration and aspiration of many. Think Macquarie Bank and its logo! Museums, the world over. Historians, collectors, investors, both local and international.

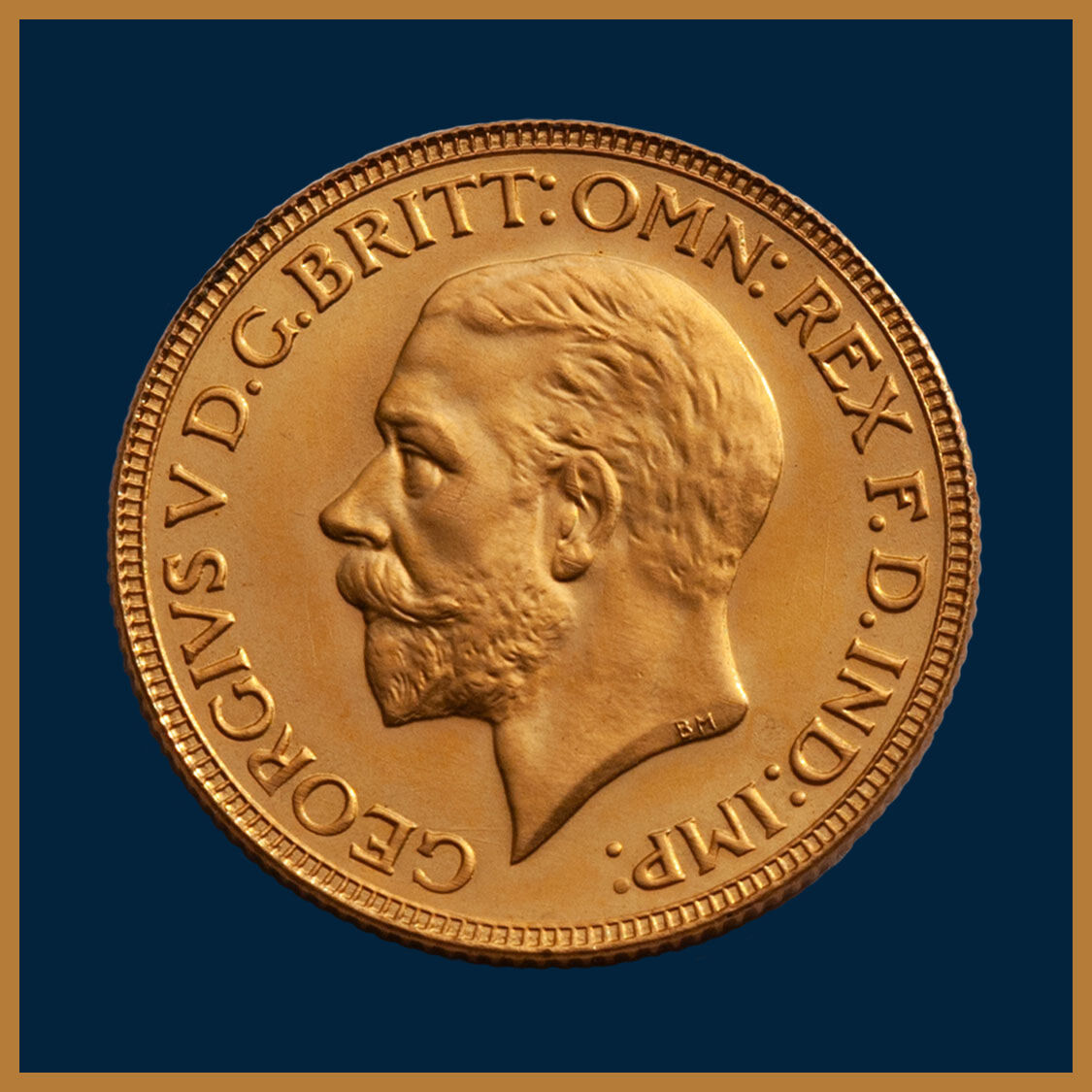

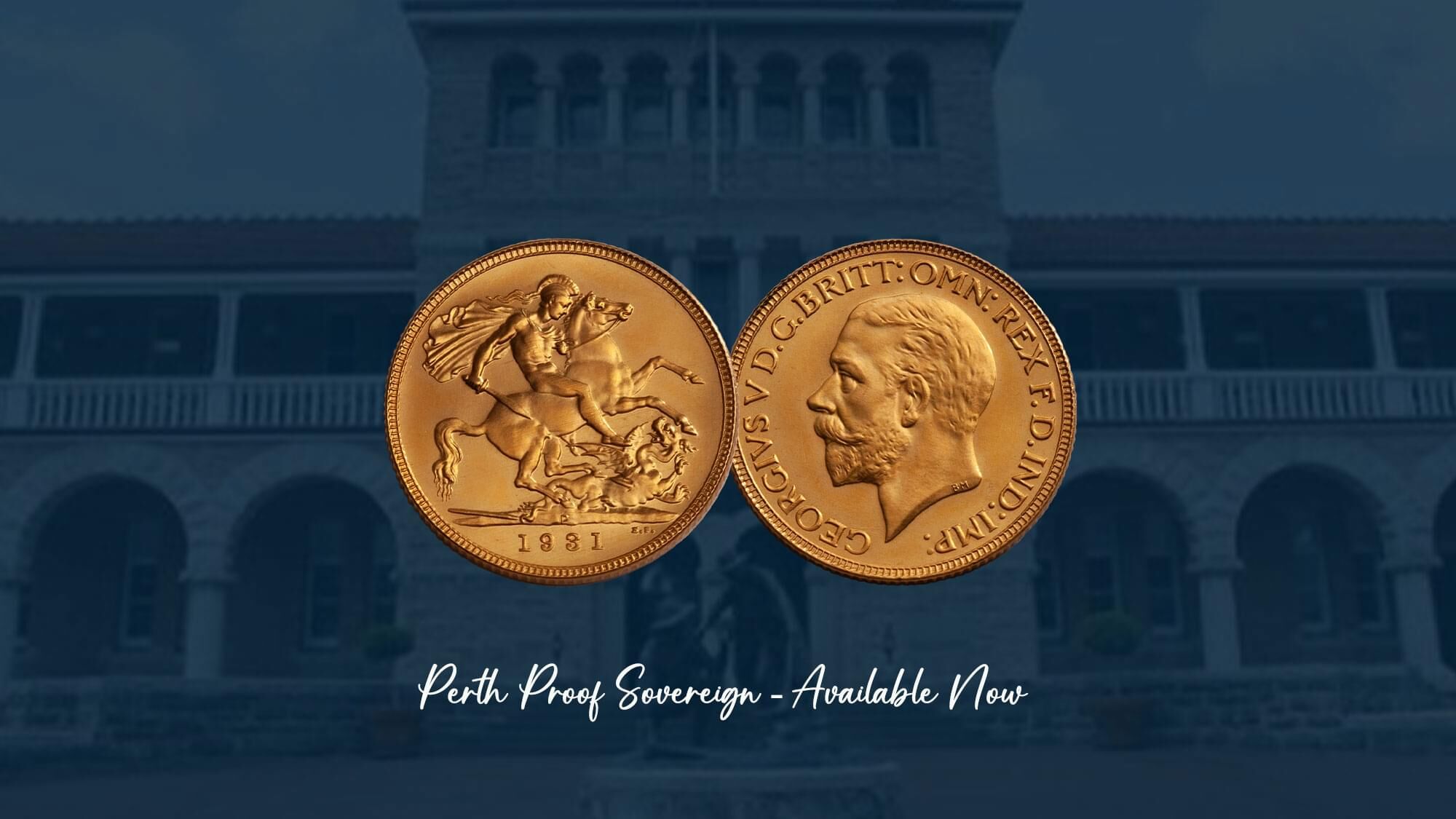

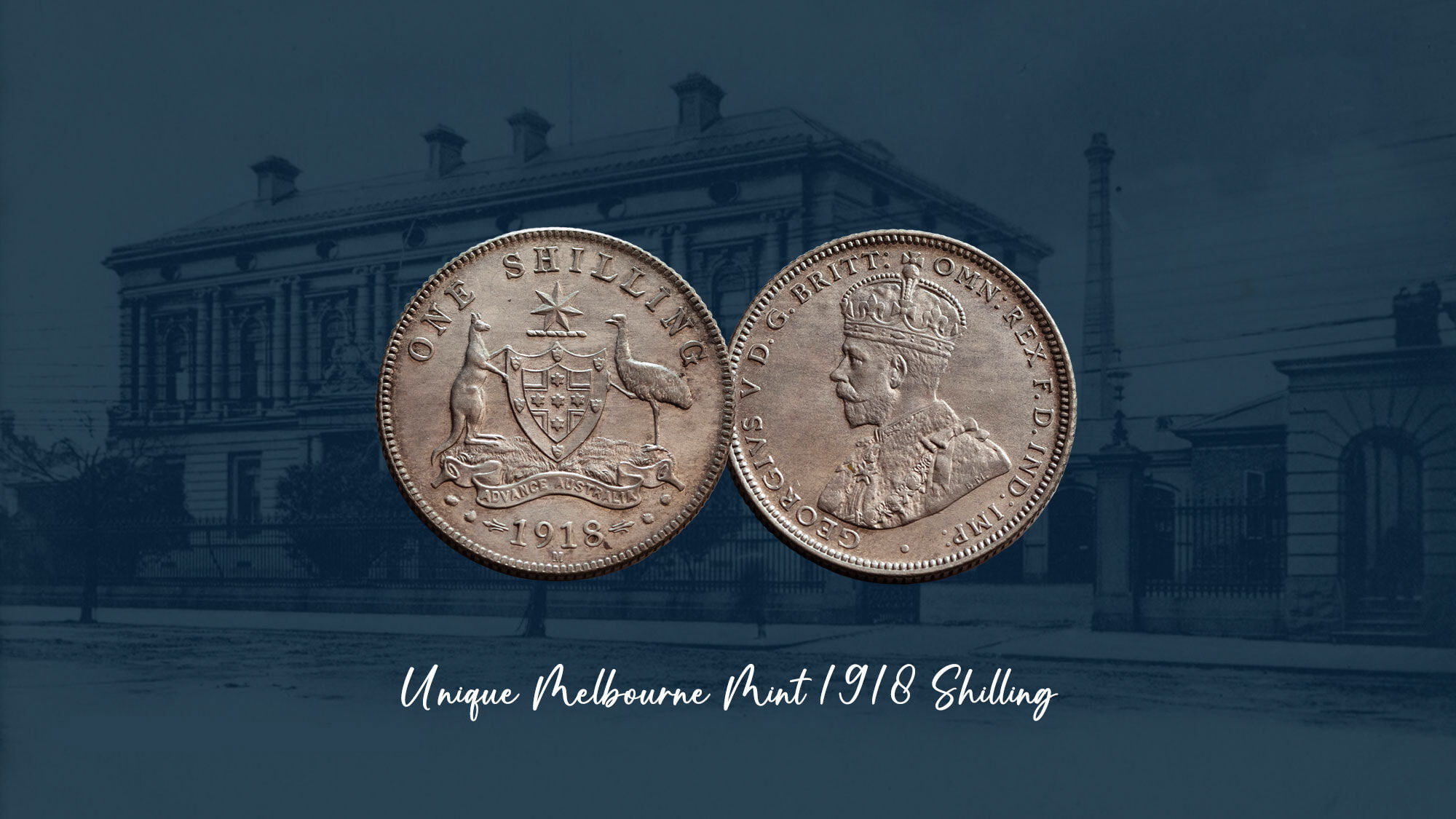

This Edward VII 1910 Proof Sovereign has a level of excellence and exclusivity that inspires widespread admiration. The coin is a celebration of the Melbourne Mint’s achievements in crafting perfection in gold. And it is unique. It represents the very best in its class.

We estimate that one thousand collectors can own a 1930 Penny. Perhaps nineteen collectors can own a veiled head proof sovereign. But only two collectors can ever own an Edward VII proof sovereign, this coin one of the two. The importance of this offer cannot be overstated.

Excerpts from our report on the Melbourne Mint proofs (in the view more section) confirm its unique status and the extreme rarity of Edward VII proofs.

Click here for more details on this Product

When the Royal Mint London or the British Museum requested a sovereign or half sovereign from an Australian Mint, they were never sent a circulation strike. They were sent a specially crafted presentation piece.

Nor would a circulation strike be presented to the monarch, gifted to a dignitary or sent to an influential collector. And a circulation strike would not be displayed at a Colonial Exhibition. Again, an individually crafted presentation piece would be specially created for the occasion.

The technical term for such a piece is 'Coin of Record'.

A Coin of Record is an artistic interpretation of coinage, a strikingly beautiful coin beyond ordinary currency. Individually crafted to standards far exceeding that required of a circulating coin, minted with a proof or specimen finish and created using special coining techniques. Whereas production of circulating coinage was dictated by Government, Coins of Record were struck at the discretion of the mint master.

Coins of Record were not produced every year and, as they were individually crafted, the process was time consuming and the mintages minuscule. For gold proofs, generally ten pieces or less. There were several occasions when only a single coin was struck.

Coins of Record of Australia's sovereigns and half sovereigns are visually stunning, distinguished by brilliant golden-mirror surfaces. And it is their beauty and their ultra-exclusivity that drives demand.

The market for Australia's gold Coins of Record was effectively established in London, in 1903, and continues to this very day right across the globe.

Recent international auction results confirm their status as a globally traded commodity, the frosted proofs of the Melbourne MInt in particular, keenly sought after by American collectors.

The Coins of Record of Australia's proof sovereigns and proof half sovereigns are the crown jewels of coinage, adding glamour and exceptionality to any collection!

The Melbourne Mint opened in 1872 as a branch of the Royal Mint London, its main function to produce gold sovereigns and half sovereigns. Its gold coin production ceased in 1931.

Three monarchs reigned between 1872 and 1931, Queen Victoria, King Edward VII and George V.

The Melbourne Mint struck Coins of Record sporadically. Of the record pieces that were produced, those of Edward VII are the least available for collectors. (Confirmed in our chart below.)

John G. Murdoch was an influential British collector. He developed a strong business relationship with the Melbourne Mint and was one of the few collectors that was regularly supplied Coins of Record from 1884 until 1901, through the Young Head, Jubilee and Veiled era of Queen Victoria.

The market for Australia’s proof gold coins is international and it is dynamic. Without the involvement of John G. Murdoch, Australia's gold Coins of Record may never have seen the light of day, permanently stored in Government archives and out of reach of collectors.

Murdoch single-handedly created a market by taking Australian gold proofs into the buy/sell environment of collectors. And he struck a perfect balance with the market (then and today) with the quantities he held.

The coins moved onto the international stage when Murdoch's collection was liquidated via Sotheby, Wilkinson & Hodge in London in 1903 following his passing in 1902.

Murdoch's death in 1902 had a dramatic impact on production of Coins of Record at the Melbourne Mint.

Technically, it fell off a cliff.

Only one Melbourne Mint 1902 Proof Sovereign is known. Formerly held by the South Africa Mint (a temporary branch of the Royal Mint, 1923 - 1941) it is now held by a private collector.

No 1902 Proof Half Sovereigns are known.

And one example of the 1910 Proof Sovereign is privately held, formerly owned by Ross Pratley and Barrie Winsor, both leading gold coin specialists. (This coin)

The proofs of Edward VII are characterised by extreme scarcity. Proofs were only struck in two years and of each, only one example is known.

The proofs of Edward VII are further characterised by extreme beauty.

The Melbourne Mint reached its zenith in proof gold coining during the era of Edward VII, the depth of design of both the 1902 and 1910 Proof Sovereigns is magnificent, sculpted, three dimensional. The fields are like golden mirrors.

Unique 1910 Edward VII Proof Sovereign struck as a Coin of Record at the Melbourne Mint.

Superb FDC

Price: $135,000

This Edward VII 1910 Proof Sovereign has a level of excellence and exclusivity that inspires widespread admiration.

The coin is a celebration of the Melbourne Mint’s achievements in crafting perfection in gold. And it is unique. It represents the very best in its class.

The proofs of Edward VII are characterised by extreme scarcity. Proofs were only struck in two years and of each, only one example is known.

The proofs of Edward VII are further characterised by extreme beauty. The Melbourne Mint reached its zenith in proof gold coining during the era of Edward VII, the depth of design of both the 1902 and 1910 Proof Sovereigns is magnificent, sculpted, three dimensional. The fields are like golden mirrors.

We estimate that one thousand collectors can own a 1930 Penny. Perhaps nineteen collectors can own a veiled head proof sovereign. But only two collectors can ever own an Edward VII proof sovereign, this coin one of the two.

The importance of this offer cannot be overstated.

Owning a Holey Dollar is about indulging in an experience, a fusion of history and prestige. And its about savouring the moment. It has been the inspiration and aspiration of many. Think Macquarie Bank and its logo! Museums, the world over. Historians, collectors, investors, both local and international.

This offer is all about seizing the opportunity and matching a Holey Dollar to suit your budget.

In a presentation befitting the coin, each Holey Dollar will be presented in a bespoke case made from Australian timbers, designed and crafted by Anton Gerner. And an individual catalogue will be prepared for each coin, with photographs and detailed information.

The five Holey Dollars have now sold. Contact us if you would like to receive advice of upcoming Holey Dollar inventory.

Click here for more details on this Product

This offer is unprecedented. Five Holey Dollars offered for sale, across a broad range of prices.

• The Holey Dollar is priced below $50,000.

• The second and third Holey Dollars are priced at $105,000 and $165,000, the latter a rare Potosi Mint Holey Dollar.

• The fourth coin is a high quality Good Very Fine with fabulous eye appeal and is priced at $225,000.

• And the fifth and final Holey Dollar is an elite piece. The best in its class, it has been exhibited twice in Australia. A rare type of Holey Dollar, with only a few known and this, the finest, priced at $450,000.

The 1813 Holey Dollar is a cultural and financial icon. Its appeal extends far beyond numismatics, driven by its immense historical significance and tangible connection to a foundational moment in Australian history ... when our first coinage was created.

And with less than two hundred available to collectors, the Holey Dollar has prestige value and investment value.

We have tapped into an extensive network to put this offer together, our aim to cater to the widest possible collector audience by offering five Holey Dollars at vastly different price points.

To this end we have worked closely with now retired numismatist, Barrie Winsor. Its no secret in the industry that Barrie Winsor has been a guiding light to many coin professionals. And a mentor to prominent collectors such as Philip Spalding and Tom Hadley of Quartermaster fame, both relying on Winsor to source material.

It has been a pleasure rekindling our numismatic relationship with Barrie, working together to present this extraordinary offer.

Both of us share a passion for Holey Dollars and an even stronger passion for the industry.

Well priced.

Price: $35,000

SOLD

Great eye appeal.

Price: $105,000

SOLD

Rare Potosi Mint.

Price: $165,000

SOLD

Impressive.

Price: $225,000

SOLD

Best in its class!

Price: $450,000

SOLD

The Holey Dollar is the nation’s first coin, minted in 1813 by order of Governor Lachlan Macquarie. As Macquarie had no access to metal blanks to create his currency, he improvised and acquired 40,000 Spanish Silver Dollars as a substitute.

To make his new coinage unique to the colony, he employed emancipated convict William Henshall to cut a hole in each Spanish dollar. Each holed dollar was then over-stamped on both sides around the edge of the hole. On one side, the date 1813 and the issuing authority of New South Wales. And the other, the value of Five Shillings.

If you look at the entire process, it is the application of the counter stamps that is the point at which the 1813 Holey Dollar is created. Prior to that, it was just a Spanish dollar with a hole in it!

The 40,000 Spanish Silver Dollars came with different dates and different design details that reflected the reigning Spanish monarch. And they were sourced from various mints around the world, each mint with a different identifying mark. As the Spanish Dollar was an internationally traded coin, most of them came to Macquarie well used. (We know that because the majority of Holey Dollars are well worn.)

As the Holey Dollar was crafted from a Spanish Silver Dollar (and not a metal blank), assessing its value has to give consideration to the original dollar. Its quality. And its rarity. Consideration must also be given to the extent of circulation once the dollar was converted to an 1813 Holey Dollar.

Valuing a Holey Dollar is therefore a multi-faceted process that takes into account seven elements. The date, the monarch and the legend of the original silver dollar. The mint at which the dollar was issued. The quality of that dollar. Now we turn to the counter stamps applied by Henshall. Are they random or precise? And are they worn?

The brief summary above is intended to explain how and why vast price differences can occur with Holey Dollars. Why one can be priced at $35,000 and the other at $425,000.

Owning a Holey Dollar is about indulging in an experience, a fusion of history and prestige. And its about savouring the moment. It has been the inspiration and aspiration of many. Think Macquarie Bank and its logo! Museums, the world over. Historians, collectors, investors, both local and international.

This offer is all about seizing the opportunity and matching a Holey Dollar to suit your budget.

1813 Holey Dollar created from a Spanish Silver Dollar that had been struck at the Mexico Mint in 1803 (Mira/Noble 1803/7).

Price: $35,000

SOLD

A Holey Dollar that has seen harsh treatment but still retains the important design details of the date, legend, mint mark. The counter stamps are also clear, the 'H' for Henshall distinct. Ex Max Stern & Co (1971), then to Philip Spalding.

Design type: 5 (Charles IV legend and portrait)

Date of the silver dollar: 1805

Reigning monarch: Charles IV (1788 - 1808)

Portrait: Charles IV

Legend: Carolus (Charles) IIII

Mint and mint mark: Mexico Mint identified by the 'M' with a small circle above it in the legend on the reverse

Quality of silver dollar : Fine

Quality counter stamps: About Very Fine

Counter stamp dies: II/4: B/4

1813 Holey Dollar created from a Spanish Silver Dollar that had been struck at the Mexico Mint in 1799 (Mira/Noble 1799/4).

Price: $105,000

SOLD

Formerly owned by Ron Stewart and Philip Spalding with strong design detail. Outstanding counter stamps the fleur de lis and 'H' for Henshall distinct.

Design type: 5 (Charles IV legend and portrait)

Date of the silver dollar: 1799

Reigning monarch: Charles IV (1788 - 1808)

Portrait: Charles IV

Legend: Carolus (Charles) IIII

Mint and mint mark: Mexico Mint identified by the 'M' with a small circle above it in the legend on the reverse

Quality of silver dollar: About Very Fine

Quality counter stamps: About Extremely Fine

Counter stamp dies: I/2: A/5

1813 Holey Dollar created from a Spanish Silver Dollar that had been struck at the Potosi Mint, Bolivia, in 1801 (Mira/Noble 1801/5).

Price: $165,000

SOLD

This Holey Dollar is defined by the rare Potosi Mint. Of the two hundred Holey Dollars held by collectors, sixteen only were created from silver dollars issued at the Potosi Mint. The Schulman name is an extra bonus for this coin, ex Jacques Schulman Sale, Amsterdam, 23 May 1910 (lot 2117).

Design type: 5 (Charles IV legend and portrait)

Date of the silver dollar: 1801

Reigning monarch: Charles IV (1788 - 1808)

Portrait: Charles IV

Legend: Carolus (Charles) IIII

Mint and mint mark: Potosi Mint, idwentified by the PTS monogram in the legend on the reverse said to be the inspiration of the '$' sign.

Quality of silver dollar: Very Fine

Quality counter stamps: Good Very Fine

Counter stamp dies: II/4: B/4

1813 Holey Dollar created from a Spanish Silver Dollar that had been struck at the Mexico Mint in 1804 (Reference Mira/Noble: 1804/8).

Price: $225,000

SOLD

A high quality Holey Dollar with exceptional eye appeal. As great force had to be exerted on the Spanish Silver Dollar to punch out the central hole. many Holey Dollars are found slightly dished and distorted. With this Holey Dollar, the silver dollar flan is flat and has not been distorted by the cutting process. This is simply a fabulous Holey Dollar, the even shape allowing the design details to be displayed to the max.

Design type: 5 (Charles IV legend and portrait)

Date of the silver dollar: 1804

Reigning monarch: Charles IV (1788 - 1808)

Portrait: Charles IV

Legend: Carolus (Charles) IIII

Mint and mint mark: Mexico Mint identified by the 'M' with a small circle above it in the legend on the reverse

Quality of silver dollar: Good Very Fine

Quality counter stamps: About Extremely Fine

Counter stamp dies: II/4: B/3

The extremely rare Charles III on Charles IV Holey Dollar created from a Spanish Silver Dollar that had been struck at the Mexico Mint in 1790 featuring the portrait of the deceased Charles III and the legend of his son, Carolus IV

Price: $450,000

SOLD

This Holey Dollar is a piece of significance and has been exhibited twice, at the Macquarie Bank in 2013 and the Royal Australian Mint in 2019. Ex Spink London privately from Andre de Clermont in 1989 and now held in a private collection in Perth.

To ensure that the colonial mints could continue their coinage production uninterrupted following the death of King Charles III, a Royal decree granted the mints the right to amend the legend to Carolus IV to acknowledge the new monarch but continue striking coins with the portrait of the deceased king.

This coin is the finest of eight privately held examples depicting the portrait of Charles III and the legend Carolus IV.

Design type: 4 (Charles III on Charles IV Holey Dollar)

Date of the silver dollar: 1790

Reigning monarch: Charles IV (1788 - 1808)

Portrait: Charles III

Legend: Carolus (Charles) IV

Quality of silver dollar : Nearly Extremely Fine

Quality counter stamps: Extremely Fine

Counter stamp dies: I/11: B/7

There is everything to like, and nothing to dislike, about this 1852 Adelaide Pound. Including the price. The coin is highly lustrous on both obverse and reverse and the prime design details of the crown and the legend, Government Assay Office Adelaide, are well defined. So too is the date '1852'. We also note that the fields and the edges are not marred by heavy knocks or gouges. A miracle given the factory environment in which it was struck. This Adelaide Pound is graded Good Extremely Fine, with just whisper touches to the high points. And is priced accordingly. Held in the one collection for the last twenty-six years, this 1852 Adelaide Pound is available now.

Click here for more details on this Product

The Adelaide One Pound is the nation’s first gold coin, struck in 1852 at the South Australian Government Assay Office, Adelaide.

Local jeweler and engraver Joshua Payne created the dies for the nation's first gold coins. The obverse declared the issuing authority, Government Assay Office Adelaide, encircling a crown and the date, 1852, the design used continuously throughout production. The reverse declared the fineness and weight encircling it's value.

With its fine design detail, the Adelaide Pound is compelling and a piece of significance, its status as the nation's first gold coin ensuring that it will never be forgotten.

And it is extremely rare with less than forty examples surviving from the first production run and perhaps two hundred and fifty from the second. Either first or second run, the Adelaide Pound is a prized possession, an iconic gold coin revered by local and international buyers.

1852 Adelaide Pound Type II

Obverse

1852 Adelaide Pound Type II

Reverse

The first production run of Adelaide Pounds was short and eventful. A cracking of the reverse die during the striking of the first fifty coins halted production.

The impaired die, featuring a beaded inner circle, was replaced and production resumed, staff electing to use a die with a different design to that used in the first run. The second die featured a scalloped inner border. The move to use differently designed dies was profound for it clearly differentiates those coins struck in the first and second run.

In the second production run, pressure was relaxed on the edges to lengthen the die usage and re-focused on the central area of the design. The reduction in pressure on the edges meant that the edge perfection achieved in the first run of coins was simply not achievable. Most Adelaide Pounds from the second run therefore show some form of weakness in the edges, particularly in the Government Assay Office area. Occasionally the weakness is exhibited all the way round. Due to the re-focus of pressure away from the edges and to the centre of the coin, the crown design is almost always well executed with flattened areas simply due to wear.

The official recorded mintage of the nation’s first gold coin is 24,648, a relatively small number given the amount of gold deposited at the Assay Office. Very few out of the mintage actually circulated, with many of them ending up in the melting pot. Assaying of the one pound samples sent to London determined that the intrinsic value of the gold contained in each piece exceeded its nominal value. The coin therefore became the target of profiteers and were exported to London and melted down.

The Adelaide Gold One Pound, struck in the first production run, is known as the Type I Adelaide Pound and fewer than forty examples survive from the first production run in varying degrees of quality.

The Adelaide Gold One Pound, struck in the second production run, is known as the Type II Adelaide Pound. It is an iconic gold coin with perhaps two hundred and fifty available to collectors.

The clear advantage of the Type II over the Type I is its affordability.

The 1852 Government Assay Office Adelaide Gold One Pound Type II, struck with the scalloped inner circle reverse die, edge with wide milling

Good Extremely Fine with lustrous surfaces on both obverse and reverse

Price: $30,000

There is everything to like, and nothing to dislike, about this 1852 Adelaide Pound. Including the price.

The coin is highly lustrous on both obverse and reverse and the prime design details of the crown and the legend are well defined. We also note that the fields and the edges are not marred by heavy knocks or gouges. A miracle given the factory environment in which it was struck.

This Adelaide Pound is graded Good Extremely Fine, with just whisper touches to the high points. And is priced accordingly.

Held in the one collection for the last twenty-six years, this Adelaide Pound is available now.

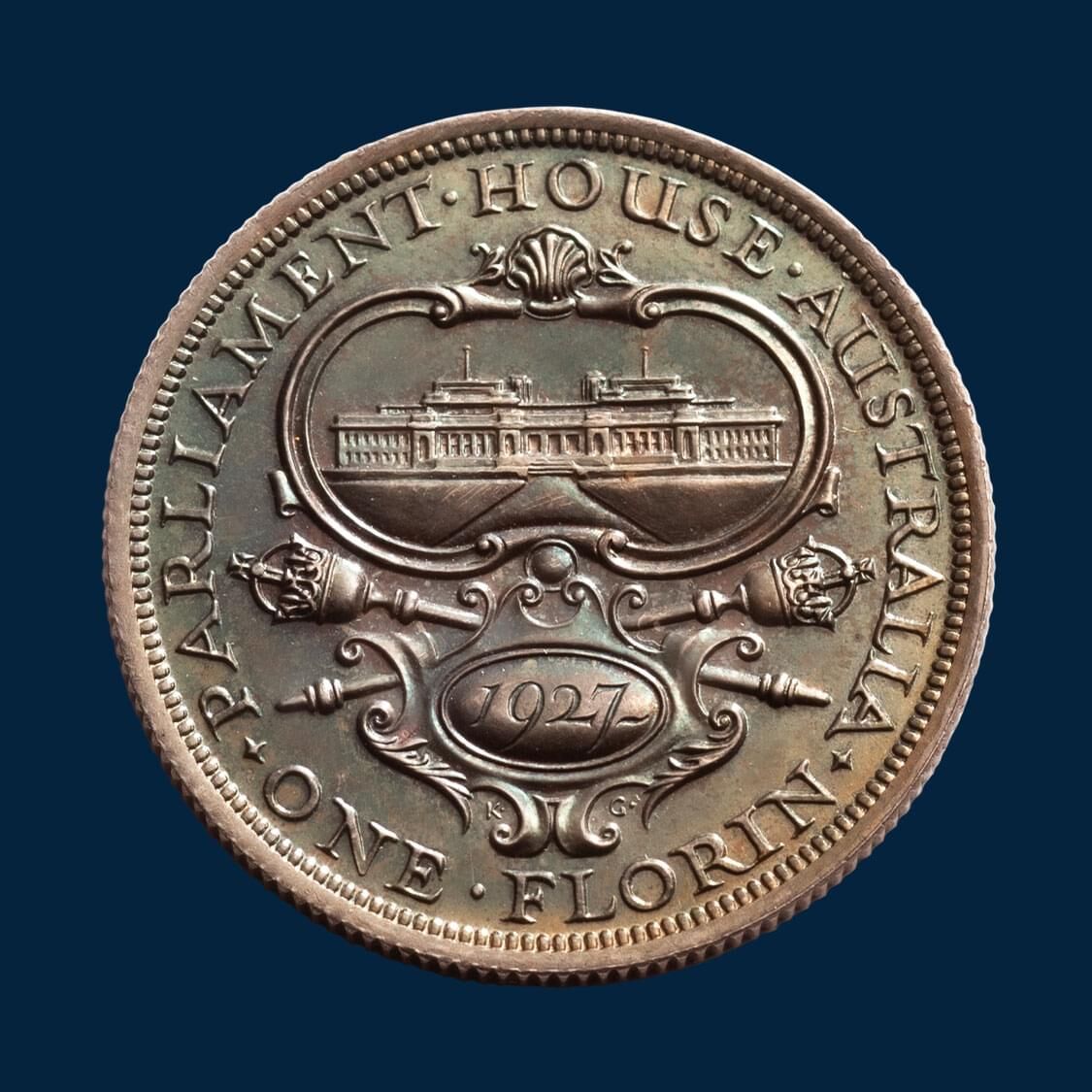

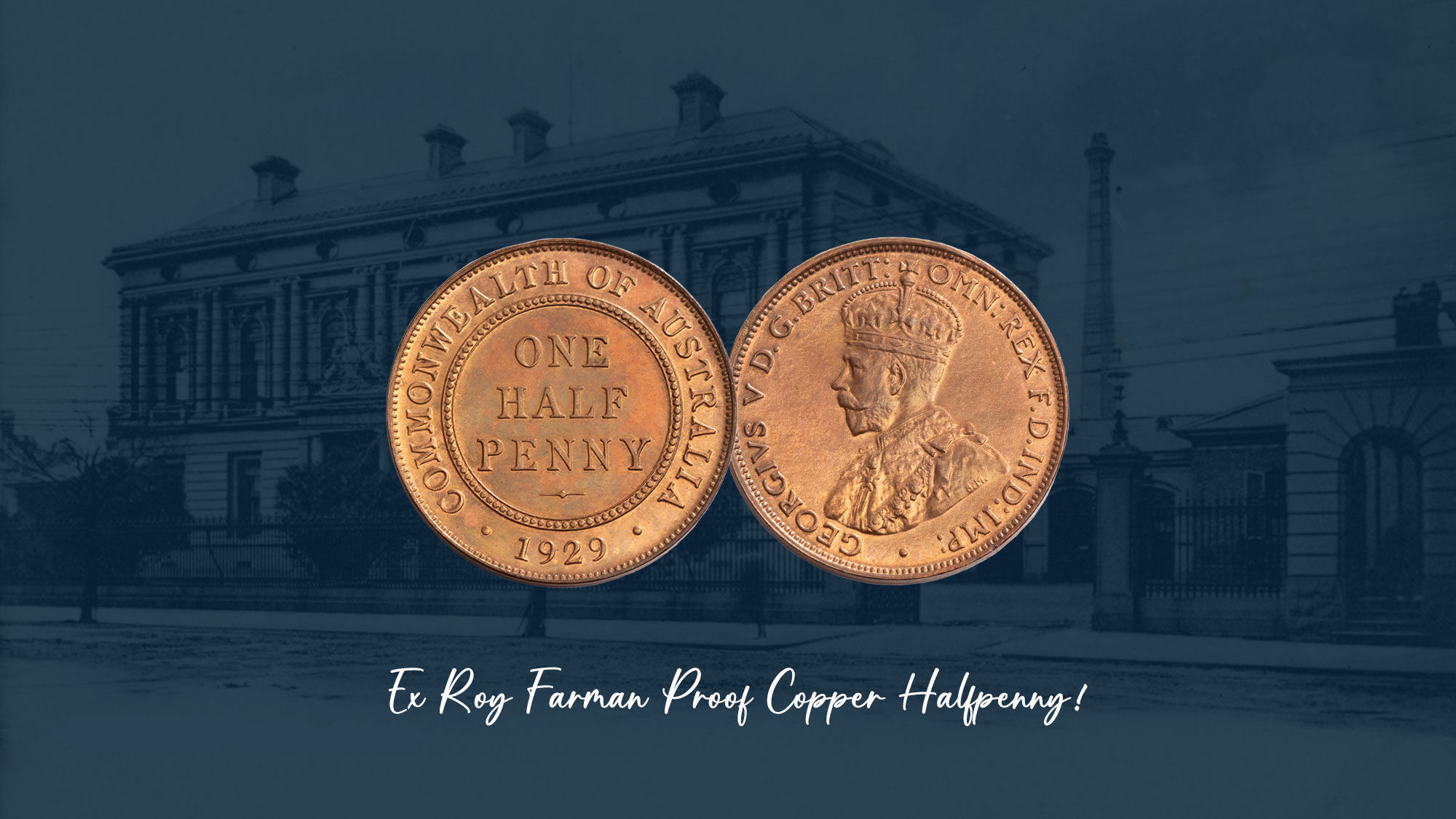

This 1927 Proof Canberra Florin is distinguished by a strong strike, brilliant mirror fields and magnificent emerald-green toning. Ex Barrie Winsor, February 2000, when it was sold to Marcus Plunkett to form part of the Treasures Collection. The coin is exceptional and is one of the few proof Canberra florins available today that is offered with a detailed provenance. And if you think the reverse looks great, wait until you see the obverse. The portrait of King George V almost leaps out of the coin!

Click here for more details on this Product

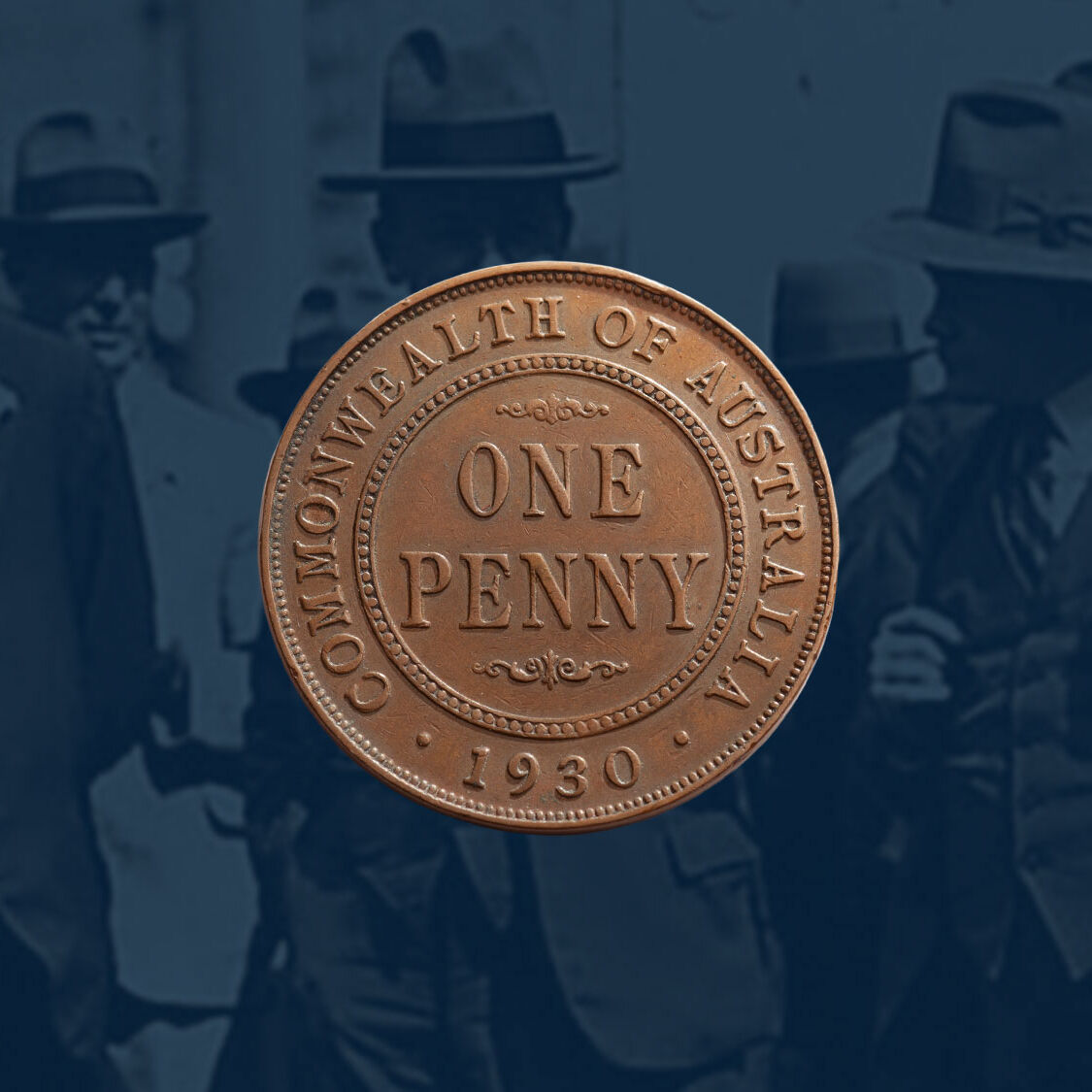

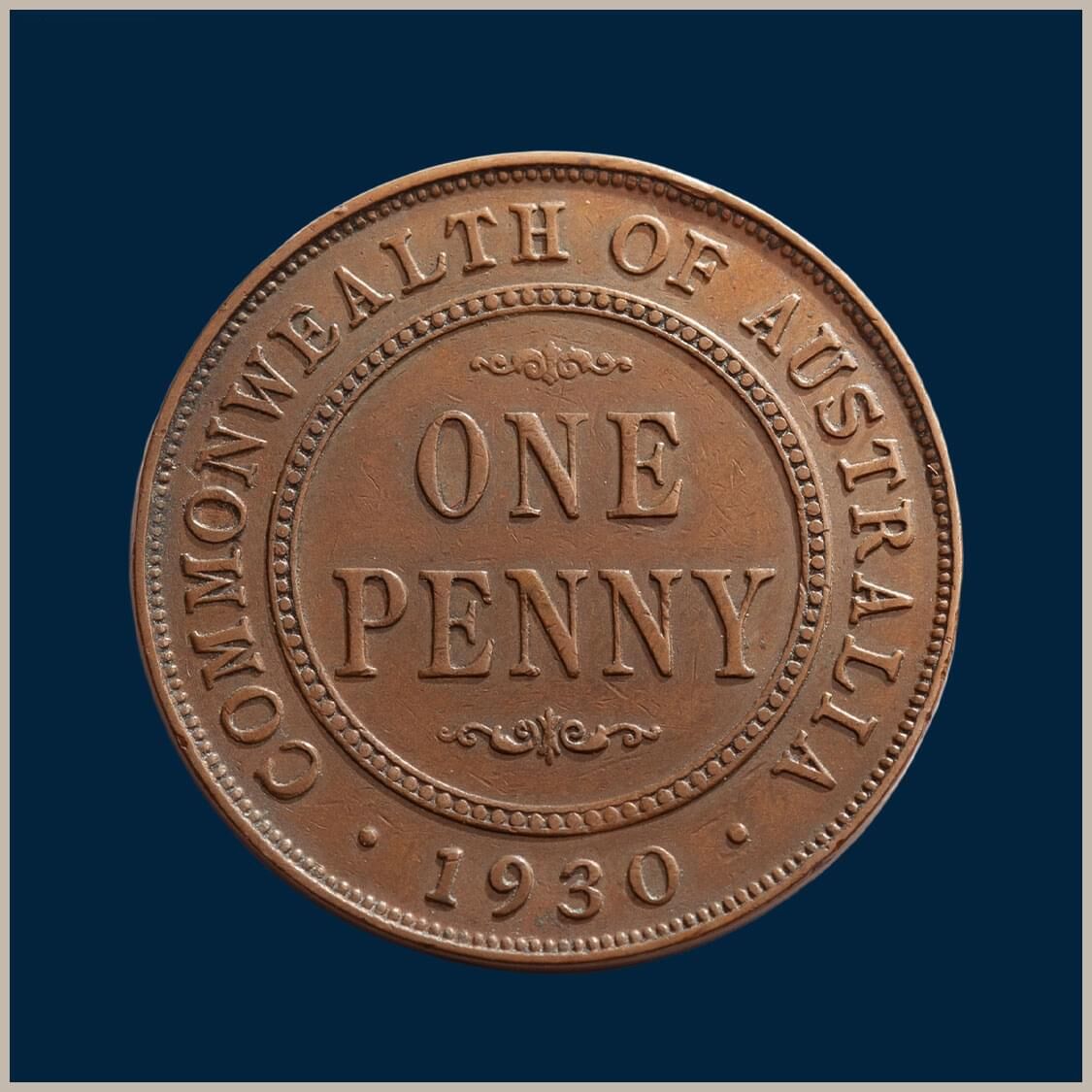

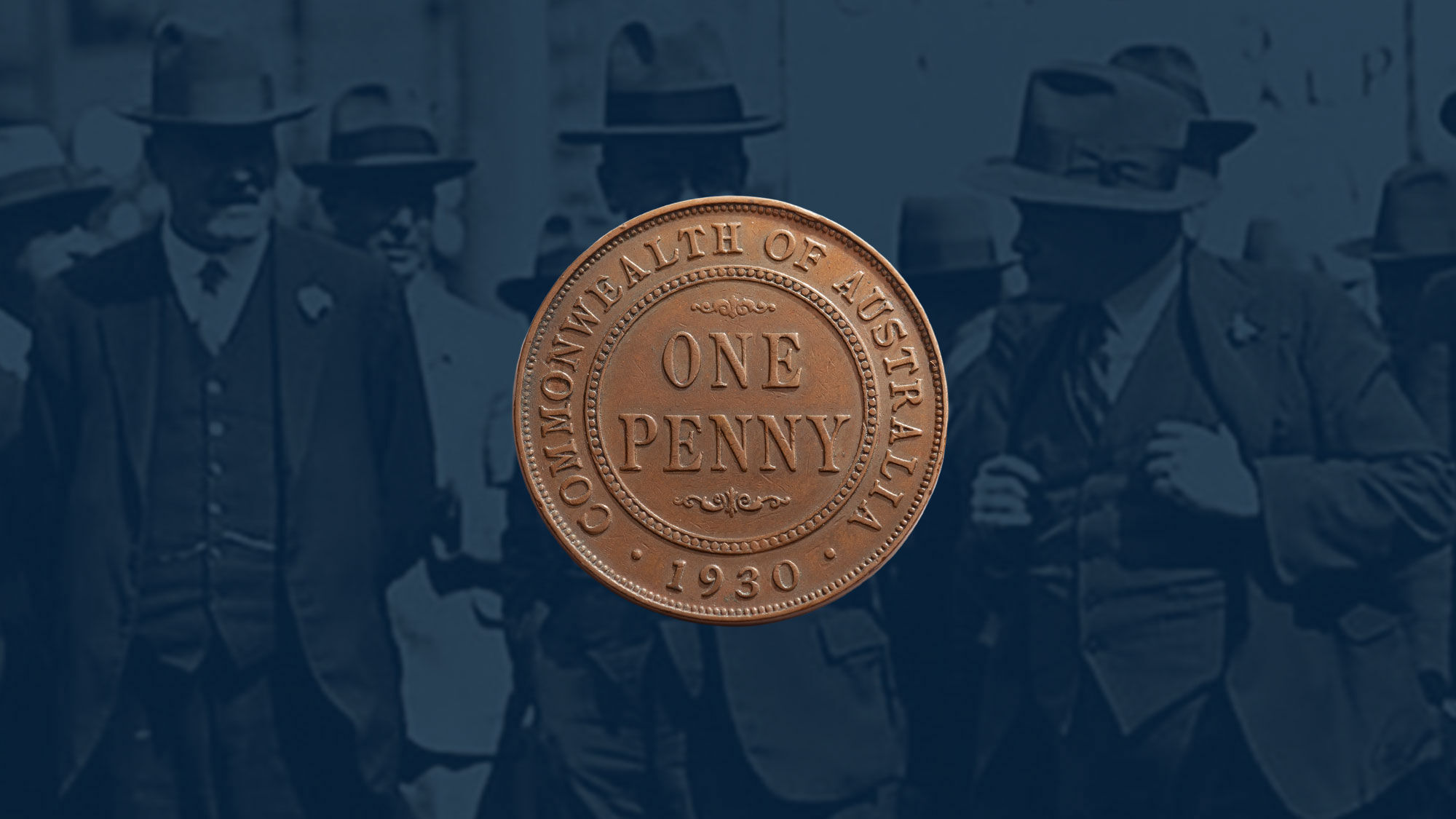

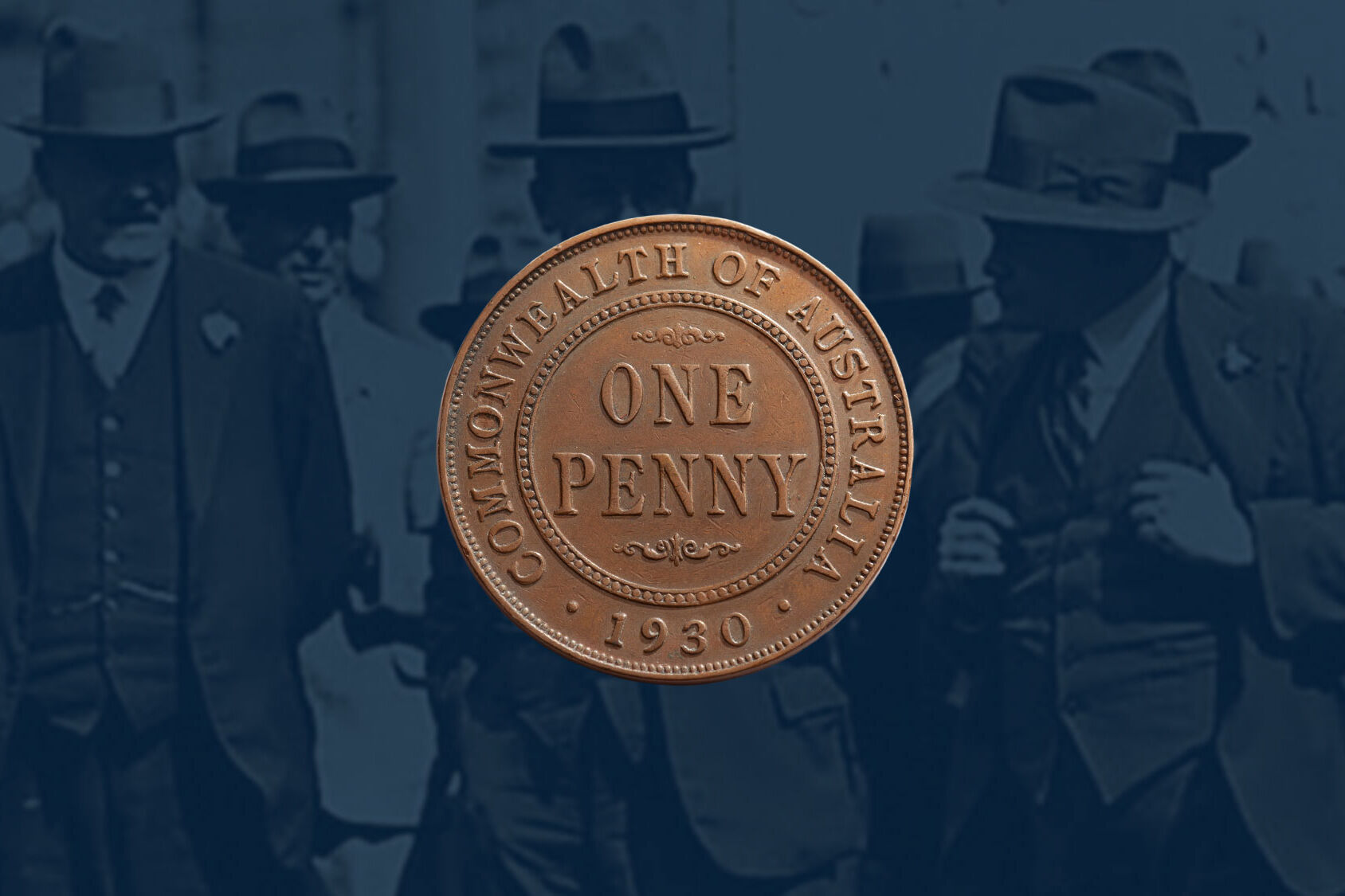

If we asked collectors to name the top five most popular and recognised Australian rare coins, without doubt the 1930 Penny would be at the top of the list.

But, the 1927 Proof Canberra Florin would, in all likelihood, be at position number two.

It is a coin that resonates with all Australians and for many collectors it's not a matter of 'if' I will buy a Proof Canberra Florin, it's 'when' I will buy one.

1. The coin has genuine rarity

While Melbourne Mint records show a mintage of 400, it is generally accepted that the issue did not sell-out, the proposed mintage too optimistic for the size of the collector market at the time. And non-collectors baulking at having to pay a premium over face value to acquire the 'proof'! The unsold coins were melted down, the mintage believed to be as small as 150.

The proofs were gifted to politicians and sold to the public without a case thereby introducing the possibility of mishandling.

So for the buyer that makes quality a priority, the waiting time for a really nice 1927 Proof Canberra Florin can be a minimum of two years. Perhaps even longer.

2. The coin is historically important

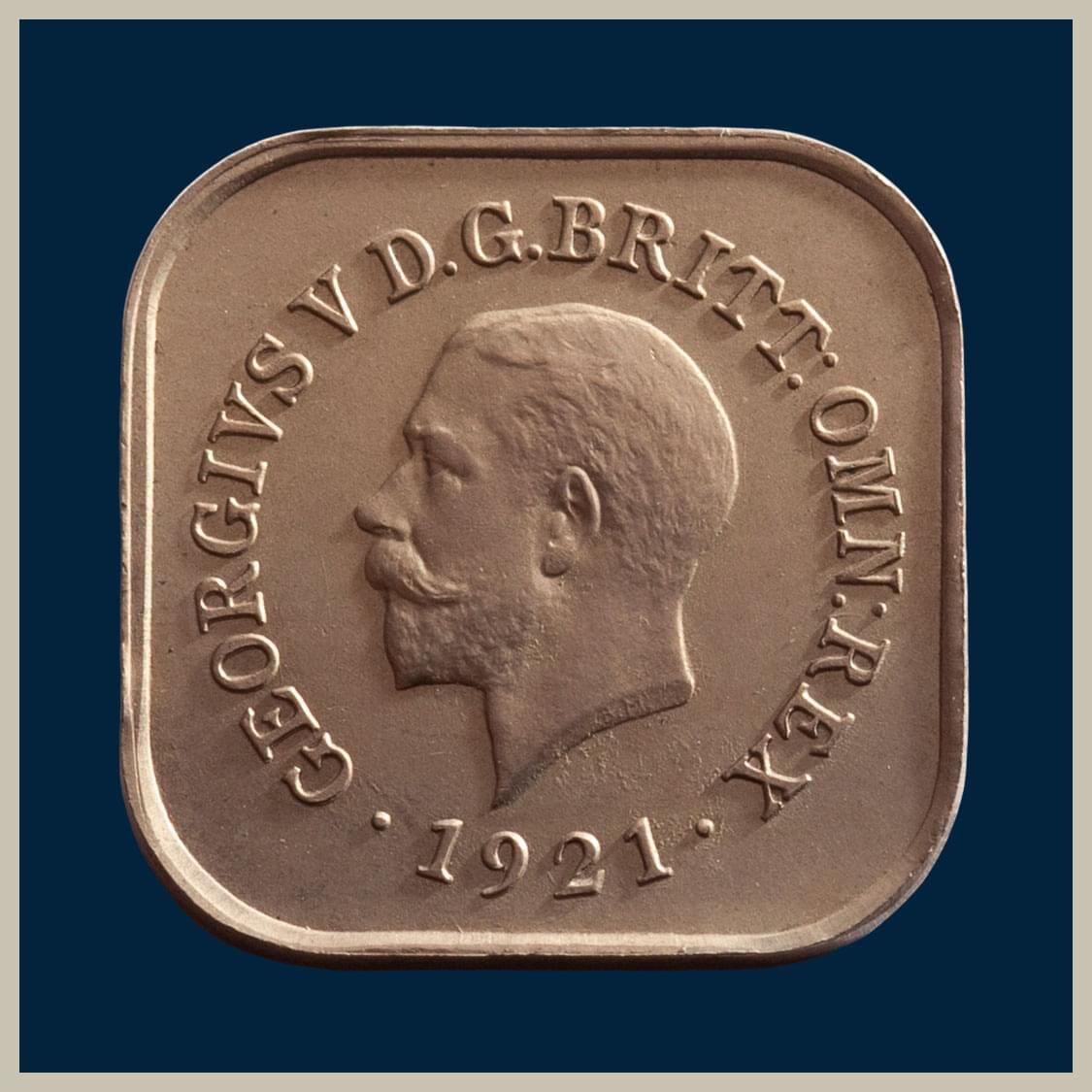

The Proof Canberra is Australia's first commemorative coin, minted for one of the most significant events in Australia’s journey to nationhood. The opening of the nation’s first Parliamentary buildings in the national capital in 1927. The coin is distinguished by a unique obverse featuring an enlarged bust of King George V, designed by Sir Edgar Mackennal.

3. The coin has a design that resonates with all Australians

In an article published in the CAB Magazine, February 2007, author and respected numismatist Vince Verheyen declared the 1927 Proof Canberra Florin "arguably Australia's most attractive predecimal silver coin". We can only agree. The reverse of 'Old Parliament House' was designed by George Kruger-Gray.

4. The coin has value and, over the long term, appreciating value

An analysis of auction realisations over the past forty years, confirms the 1927 Proof Canberra Florin is extremely scarce. On average one pristine example is offered every few years. We also note the coin has enjoyed solid price growth. In the 1980s, a Proof 1927 Canberra Florin was selling for approximately $1000 - $1500 at auction. In the 1990s the coin was fetching betwen $4000 - $6000. Two decades later, top quality Proof Canberra Florins are commanding prices in excess of $20,000.

1927 Proof Canberra Florin

1927 Proof Canberra Florin

This Proof Canberra Florin is worth owning!

Using the naked eye, move the coin through the light, allowing it to reflect off the fields. Both obverse and reverse fields are brilliant, highly reflective. It is as though you are looking at a mirror.

• The emerald-green toning is magnificent!

• The edges are intact and solid.

• Under a magnifying glass we note, the striations, between the 'ONE' in the legend and the oval containing the date 1927. They are strong.

• Vertical striations on the obverse are similarly distinct and strong.

• Heavy striations equates to well brushed dies. Well brushed dies equates to a razor sharp, three dimensional coin design. And the three parliamentary steps are present!

• The fields are impressive. Amazing for a coin struck nearly a century ago. Our comment here is that the coin's former owners have always respected and cherished its quality for its state of preservation is remarkable.

1927 Proof Canberra Florin minted for one of the most significant events in Australia’s journey to nationhood, the opening of the first Parliamentary buildings in the national capital, Canberra.

Price: $25,000

This 1927 Proof Canberra Florin is distinguished by a strong strike, brilliant mirror fields and magnificent emerald-green toning. Ex Barrie Winsor February 2000 when it was sold to Marcus Plunkett to form part of the Treasures Collection.

The coin is extraordinary and is one of the few Canberra florins available today that is offered with a detailed provenance.

Exhibited at the Melbourne Mint, Williams Street Melbourne, 29 November 2011 in the launch of the Treasures Collection.

This is an impressive 1930 Penny. We note it’s been almost a year since we last offered one of this calibre. And at this price. The coin is elegant. The coin has finesse and is for the collector that has been sitting back waiting for the ‘right’ 1930 Penny to come along. It is an exciting 1930 Penny, for the exceptional quality traits it possesses. The reverse is graded Very Fine, the coin having crisp upper and lower scrolls, well-defined inner beading, strong legend and strong date. The obverse is graded Nearly Very Fine with an almost full central diamond and six plump pearls. We also note the years of usage have treated it very, very kindly. It is an original, intact, well struck 1930 Penny with glossy fields and minimal signs of usage. The past fifty-plus years in the business have taught us that you do not see 1930 Pennies like this every day. Or every month. Or every year for that matter!

Click here for more details on this Product

There are three basic steps involved when examining a 1930 Penny.

The first step is to look at the coin in the flesh using just the naked eye. A truly great coin will always look good to the unaided eye. And this coin is very impressive!

On the reverse, the upper and lower scrolls are strong and well defined. The inner beading which is invariably weakly struck between the 4 o'clock and 6 o'clock area is also well defined. The legend 'COMMONWEALTH OF AUSTRALIA' and date '1930' are powerful. Moving the obverse through the light you see the complete lower band of the crown. You also observe the strong design details of the monarch's robes. We also comment the handsome chocolate brown toning on both obverse and reverse and the edges which are solid.

The second step is to take up a magnifying glass and examine the coin in detail. The eye glass re-confirms what we have seen to the naked eye and much, much more. We have graded this coin Nearly Very Fine on the obverse which indicates that there are nearly four sides of the central diamond and six crisp pearls. The oval to the left of the central diamond is almost intact. The reverse is graded Very Fine. The coin has minimal marks in the fields and no unsightly gouges.

The final step is to re-visit the coin with the naked eye. Just to make sure that you have taken everything in. Start with the edges and work your way in, the inner beading, upper and lower scrolls, fields. And on the obverse, start with the edges, then the portrait and the fields.

The final assessment of this 1930 Penny confirms that it is a great coin and passes our three-point assessment with flying colours.

A simply fabulous 1930 Penny, with a very impressive reverse

A simply fabulous 1930 Penny with an equally impressive obverse

There are many reasons why collectors love the 1930 Penny and one of the prime reasons is its financial reliability.

It is a solid coin. And this genuinely counts. In fact, we would go one step further and say that over the long term the 1930 Penny has probably been one of our most consistent and trustworthy numismatic performers.

The second reason is that the 1930 Penny is as Australian as you can get. Struck during the Great Depression, the 1930 Penny is the nation’s glamour coin and is unrivalled for popularity, enjoying a constant stream of demand unmatched by any other numismatic rarity.

The third reason is that the 1930 Penny is sought after at all quality levels and all dollar levels. It is in many respects an industry phenomenon, for in a market that is quality focused the 1930 Penny is keenly sought irrespective of its quality ranking. And growth over the mid to long term has been significant across all quality levels. Well circulated (Fine) 1930 Pennies were selling for £50 in the 1950s. A decade later, by decimal changeover, the coins were fetching £255 ($510). By 1988, Australia's Bicentenary, a Fine 1930 Penny had reached $6000. The turn of the century saw 1930 Penny prices move to a minimum of $13,000. Twenty years later prices have more than doubled. And with a 100th anniversary just five years away, the push to acquire Australia’s favourite Penny is really on.

Commonwealth of Australia 1930 Penny, a superb example of Australia's most sought after copper rarity with an almost full central diamond and six plump pearls.

Nearly Very Fine / Very Fine

$40,000

Strong upper and lower scrolls, prominent '1930' date, even chestnut toning, inner beading between 4 and 6 o'çlock strong. The coin stands up to scrutiny under the glass revealing an almost full central diamond and six clear and plump pearls.

The past fifty-plus years in the business has taught us that you do not see 1930 Pennies like this every day. Or every month. Or every year for that matter!

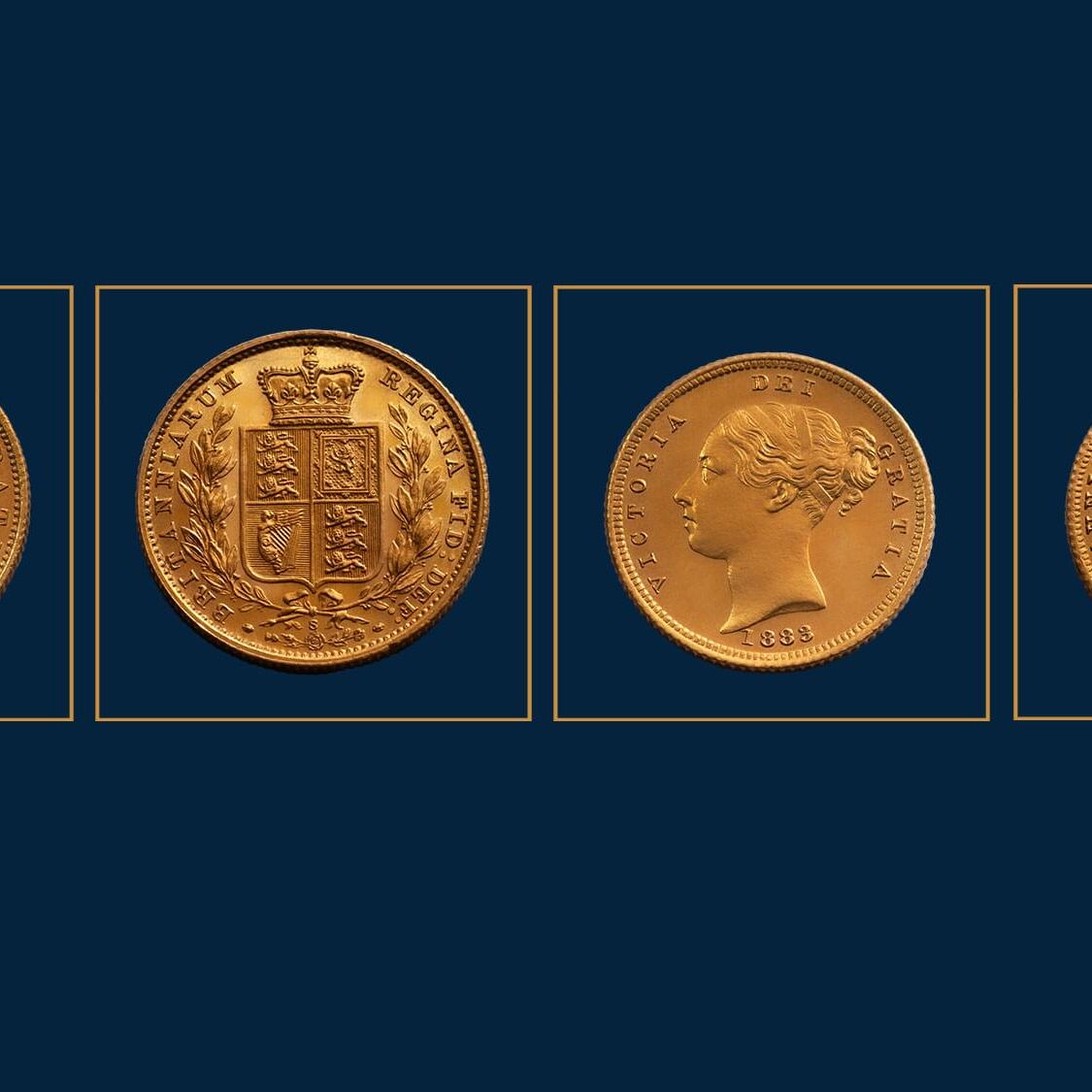

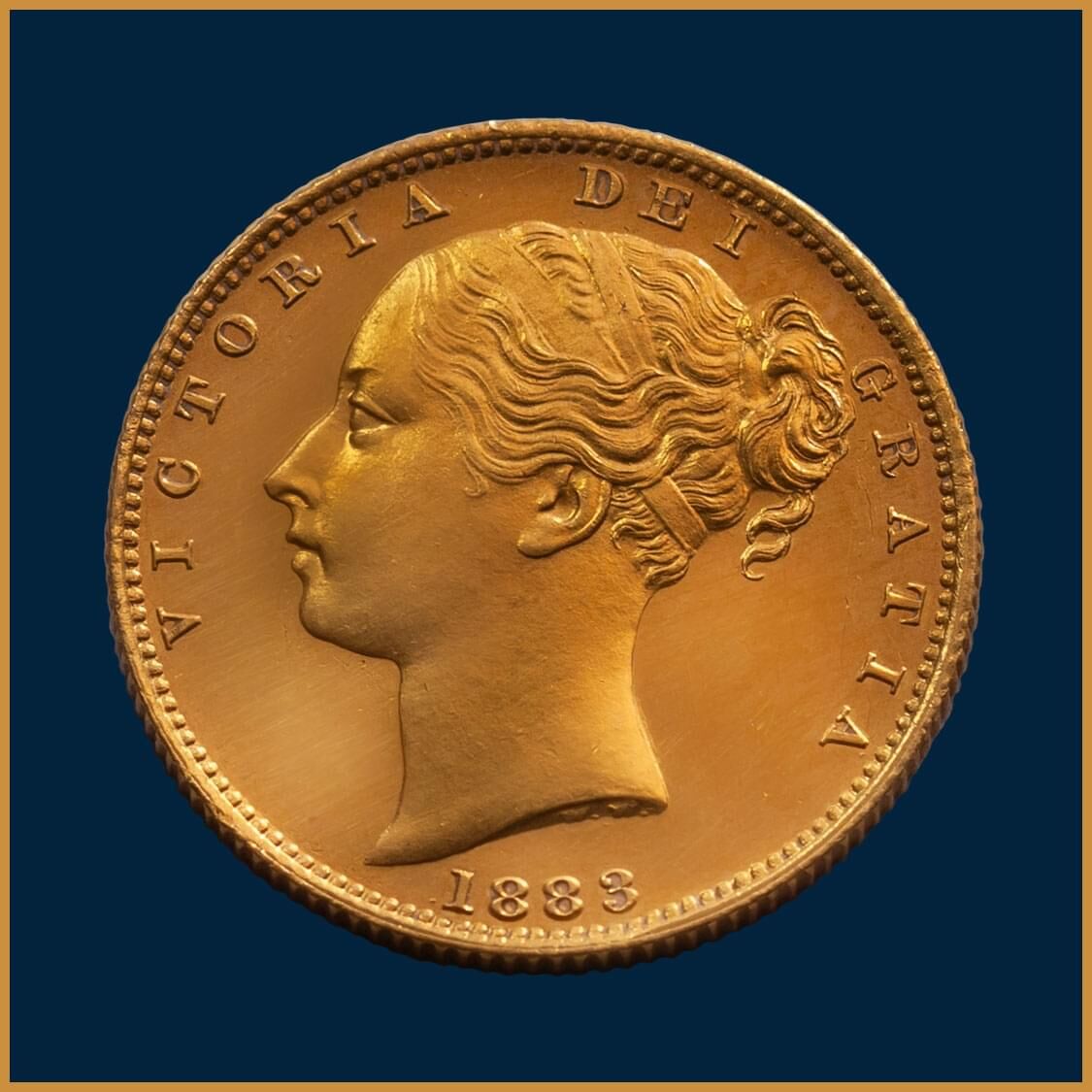

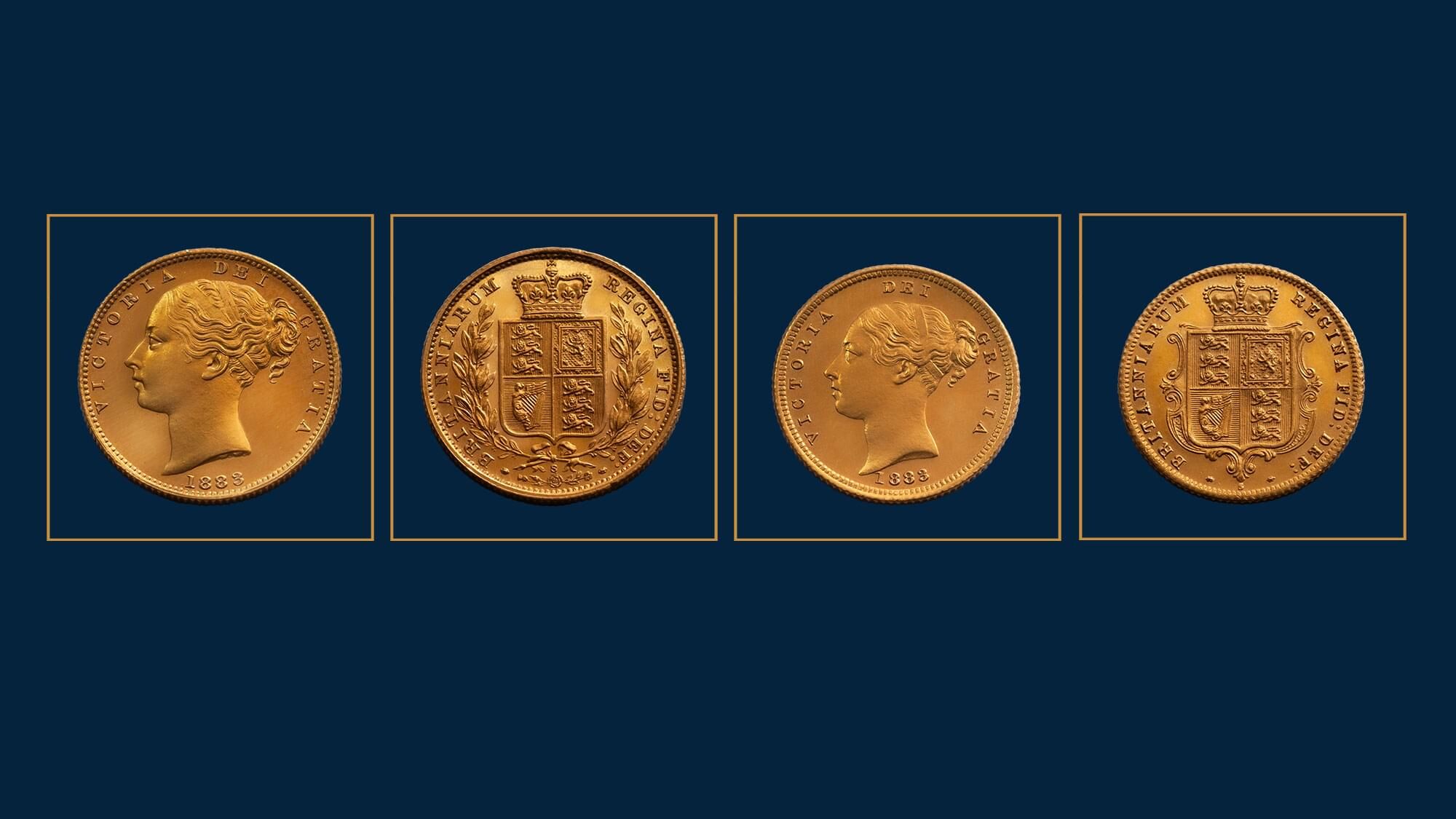

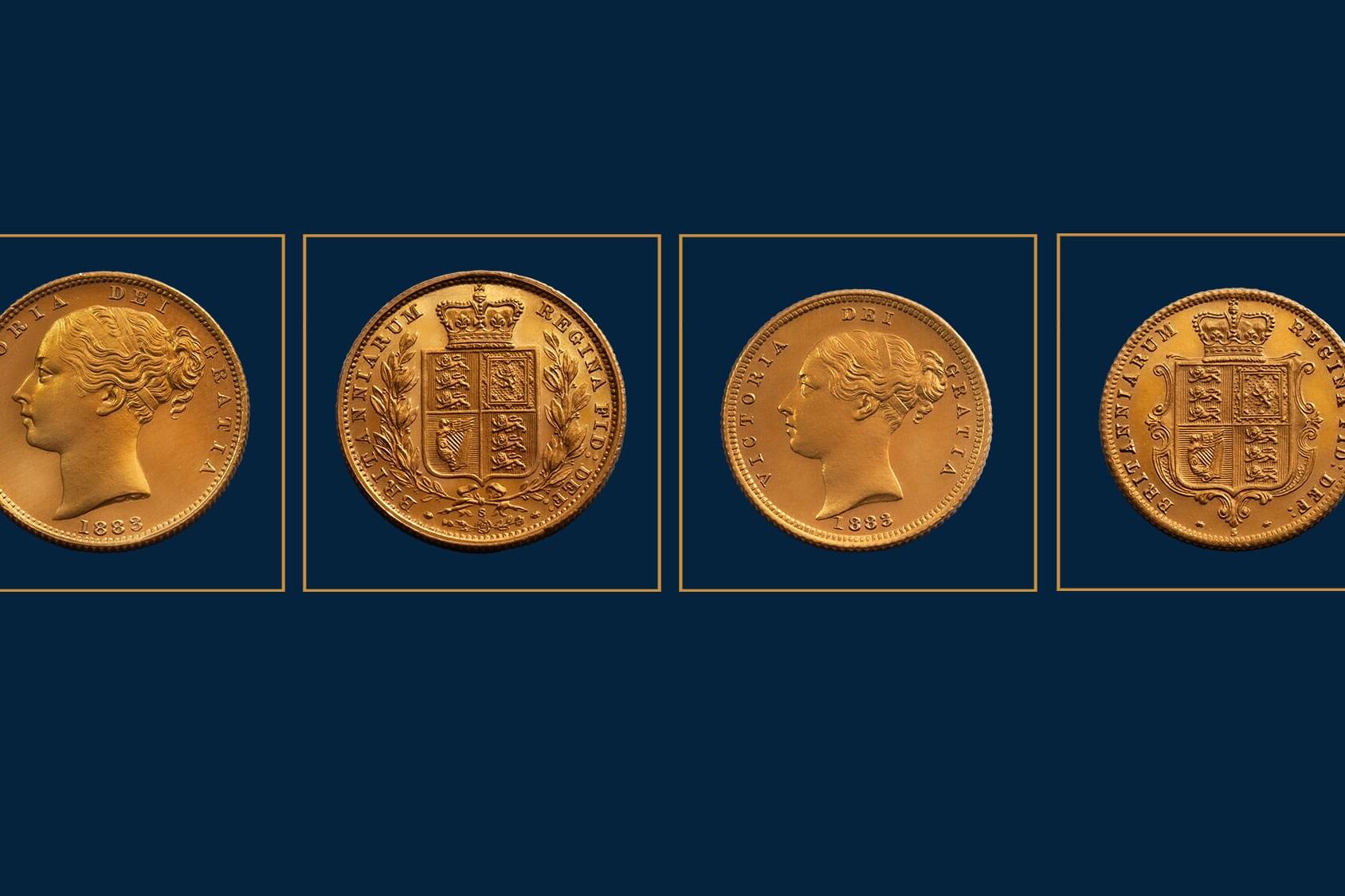

We are just putting the finishing touches to a report on the Sydney Mint proofs. Our study highlights their extreme scarcity. With pairs the ultimate in rarity. This unique Sydney Mint 1883 Proof Sovereign and 1883 Proof Half Sovereign pair will be available in 2026. Reservations and/or early enquiries are welcome.

Click here for more details on this Product

1883 Proof

Half Sovereign

1883 Proof

Sovereign

1883 Proof

Sovereign

1883 Proof

Half Sovereign

1883 Proof Sovereign and 1883 Proof Half Sovereign struck as Coins of Record at the Sydney Mint

Sydney Mint proofs are inordinately rare and this pair unique.

Available in November.

Reservations and/or enquiries welcome.

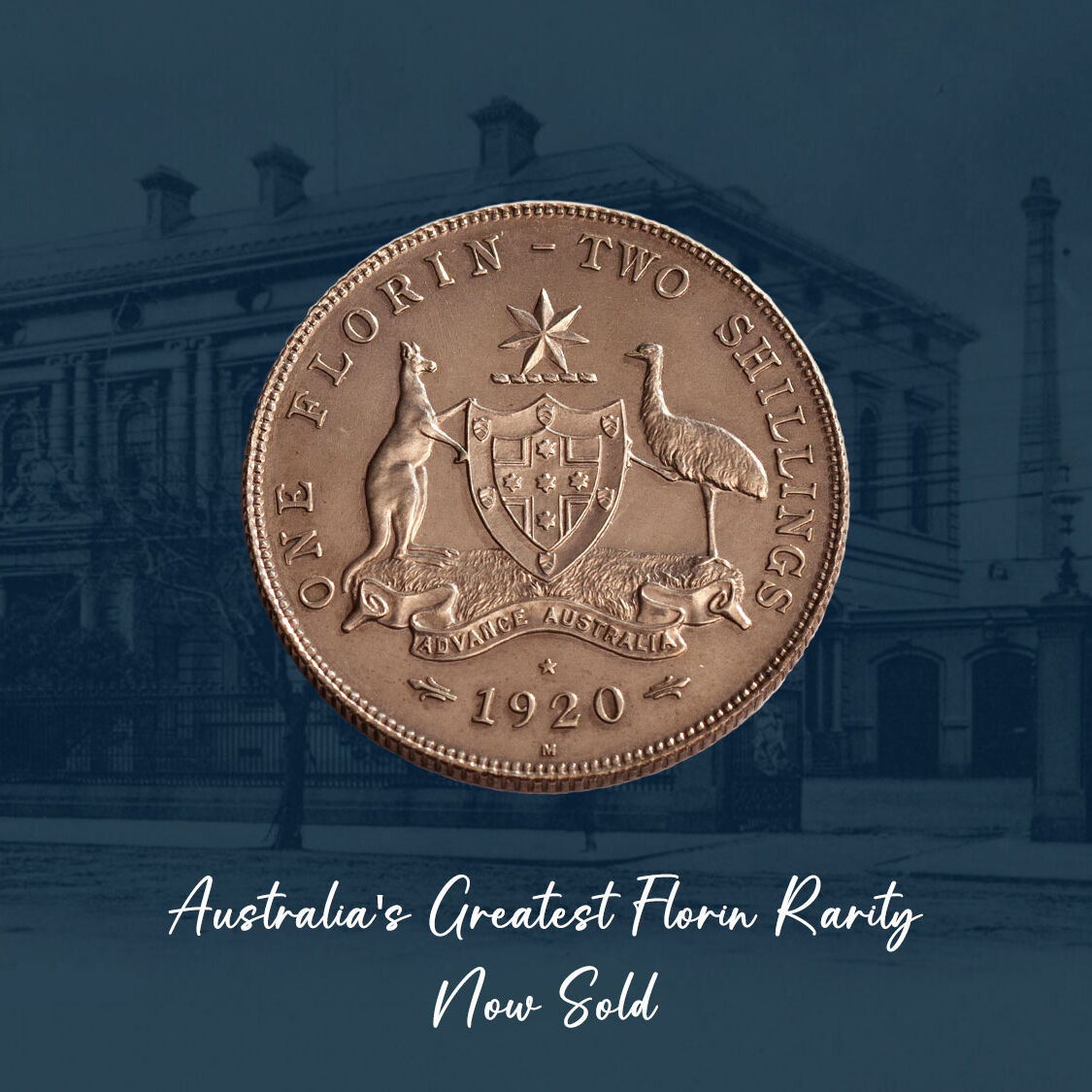

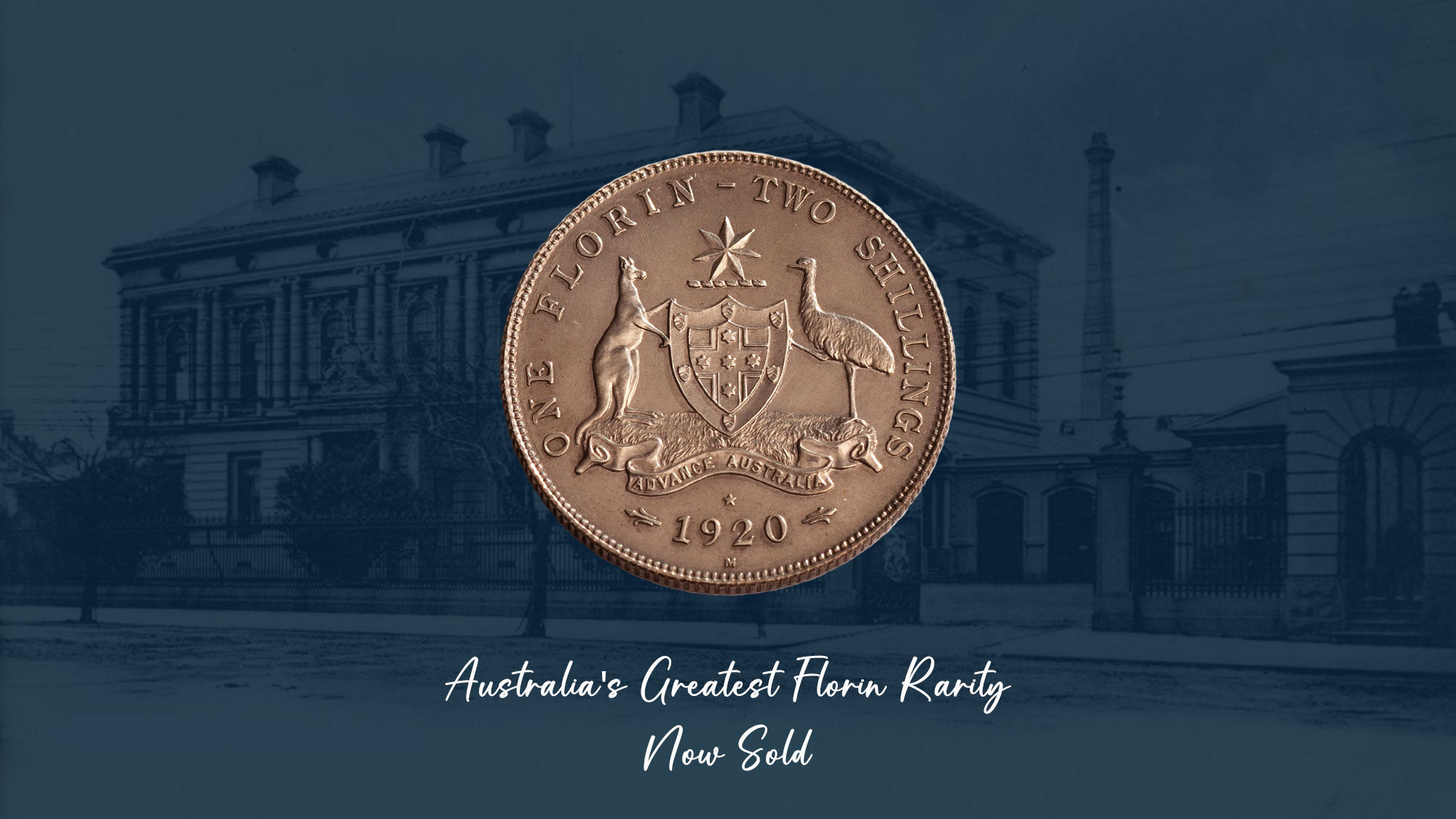

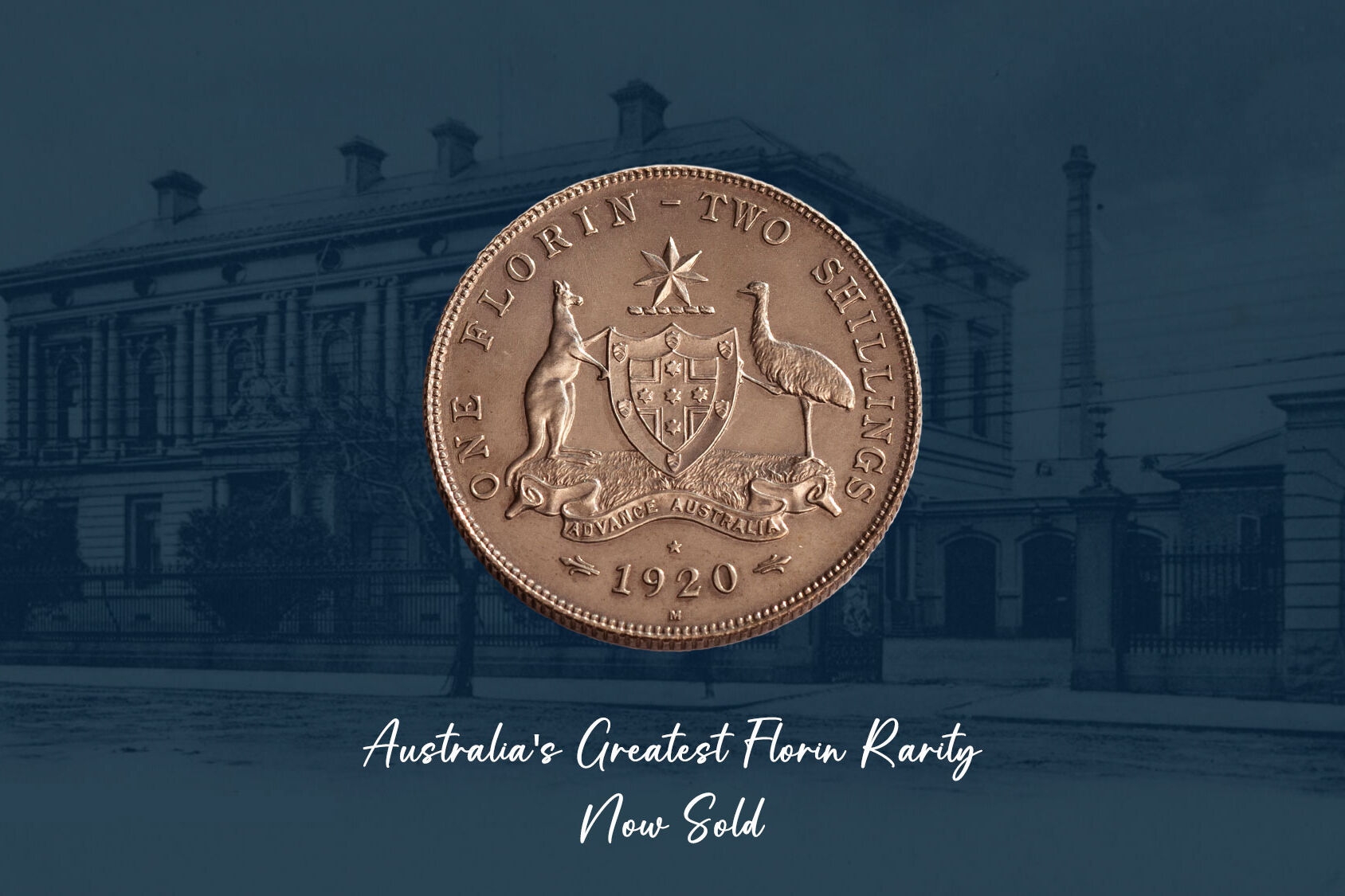

Sale number 24, conducted by Spink Auctions (Australia) in March 1988 was one of the company's most important auctions; a bicentennial celebration of all that was great in the Australian rare coin industry. The breadth and depth of excessively rare, high quality coins was compelling and overwhelming and was an event that is unlikely to be repeated. The auction made history! Out of the glittering array of esteemed rarities, a 1920 Star Florin was chosen to appear on the front cover of the catalogue. This is perhaps the simplest and easiest way of conveying the importance of the 1920 Star Florin to the industry. The coin is Australia's greatest florin rarity - the rarest florin struck for circulation. One of only seven produced at the Melbourne Mint as part of a specially controlled circulation strike, three of which are held by private collectors. And this example, one of the three ex Morton & Eden London, with superb detail and impressive satin surfaces.

Click here for more details on this Product

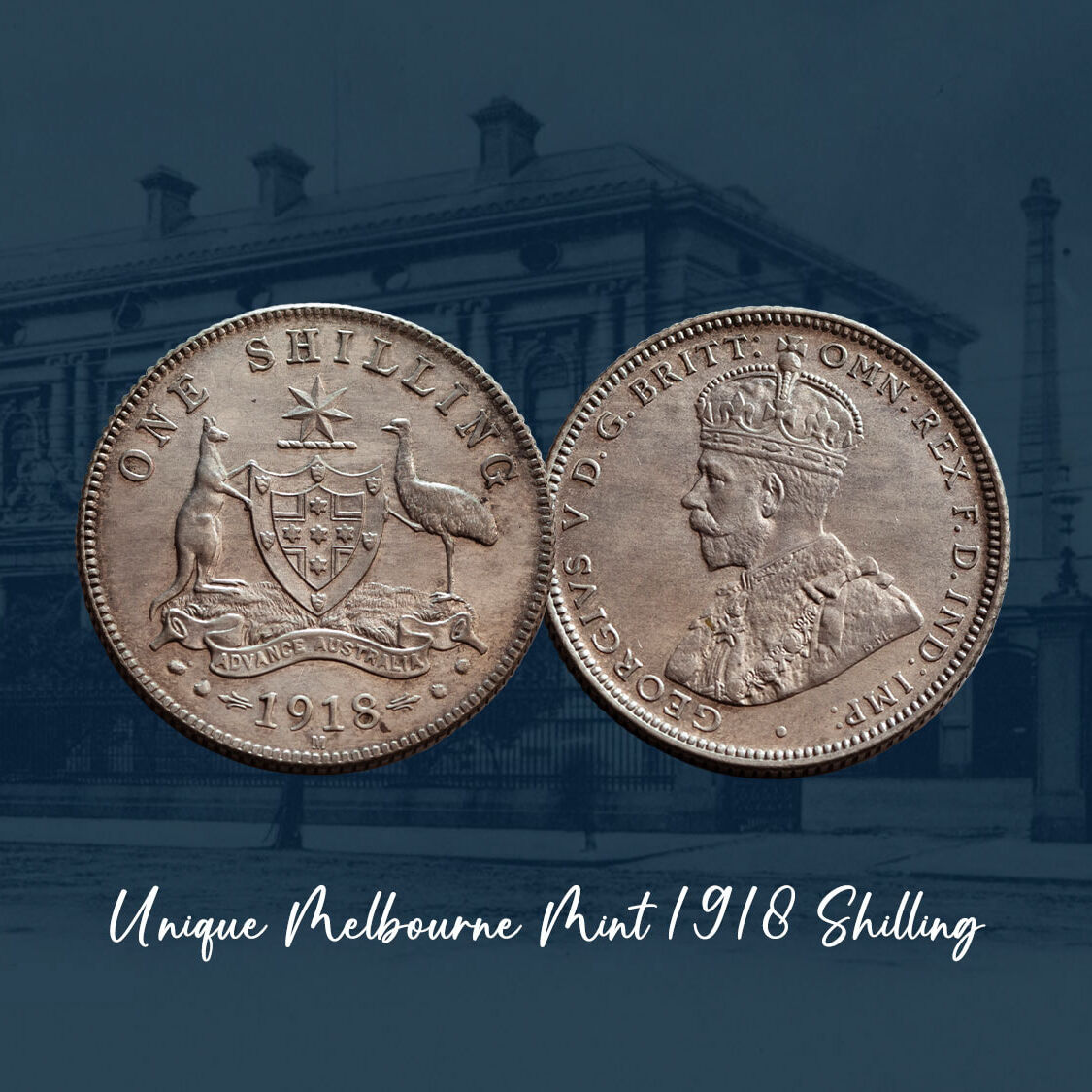

Rarity and circumstance have made the 1920 Star Florin one of Australia's greatest coin rarities.

In 1920, no florins were struck for general circulation. Seven florins were however produced at the Melbourne Mint as part of a specially controlled circulation strike and each coin featured a star above the date.

Distribution of these prized pieces was heavily restricted. Influential collector Albert Le Souef, (a Deputy Master of the Melbourne Mint between 1921 and 1926), obtained one of the seven. Three examples were retained by the mint with three heading to London, the Royal Mint the main recipient.

Aside from the Le Souef's coin, a further two have since emerged in the private sector. This coin acquired out of London and the other, sold on behalf of the Melbourne Mint museum through an Australian auction house as part of a fundraising exercise, late in 1988.

As to why no circulation florins were struck in 1920. Wildly fluctuating silver prices posed a serious issue for Governments, such as Australia, that were striking their coins in sterling silver.

The possibility that the intrinsic value of a coin would exceed its face value was a real one. The Government pondered a debasement of its coinage to lower the costs.

As to why the star appeared above the date. The dies were re-worked just in case the Government changed its mind and decided to strike a mintage of circulating florins with a reduced silver content, the star to signify the debasement.

History records that only seven circulating florins were struck in 1920, this coin one of the seven.

It is Australia's greatest florin rarity - the rarest florin struck for circulation.

Melbourne Mint

1920 Star Florin

Melbourne Mint

1920 Star Florin

The 1920 florins, showing the star above the date, were prepared as a result of a sudden rise in the price of silver that caused Great Britain and many other countries to reassess the silver content of their respective currencies.

Britain abandoned around 800 years of tradition when it reduced the finesse of its Sterling silver (92.5% pure) coins to an alloy of 50%. Canada also moved from the 92.5% standard down to 80% while British West Africa dropped silver issues completely in 1920 in favour of nickel and nickel brass coins.

Australia considered a similar move but in a gesture which cynical taxpayers of today would find very refreshing, the government wanted the public to be completely aware that the new coins would contain less silver.

According to the former numismatic curator of the Museum of Victoria, John Sharples, the normal order for 1920 dies for the silver coins had been placed in July 1919. At that time the intrinsic worth of the silver was less than the face value of the respective denominations and so no special instructions were issued in respect to the dies being prepared by the Royal Mint in London.

However by March 1920 the situation had changed drastically. According to John it was decided to prepare new dies which featured smaller date figures to differentiate the debased coins from the earlier issues.

Judging from correspondence that came back from London, it would appear that the mint had already started work on the dies or was too busy with other projects. A suggestion came back that a star above the date would not only be more noticeable but could be produced more easily and quickly than reworking the date.

This change was accepted by Melbourne and working dies for 1920 and punches for 1921 were ordered with the star. By August 1920, the Melbourne Mint had received thirty pairs of working dies for the florin and shilling denomination.

By the time everything was in place the silver crisis had passed. The silver price dropped, and neither the reduction or a circulation version of the 1920 florin eventuated.

No 1920 dated florins were issued for circulation. Three other denominations were struck for circulation in 1920, the shilling, sixpence and threepence. None carried the star. On some of the 1920 shillings (and even the sixpences) a small indentation above the date can be seen in high-grade coins, where the star has been removed on the die.

Strangely enough, the 1921 shilling still carried the star, although the silver crisis had long passed.

The excessively rare Melbourne Mint 1920 Star Florin, FDC

Ex Morton & Eden London 2007

Price: $95,000

Sale number 24, conducted by Spink Auctions (Australia) in March 1988 was one of the company's most important auctions; a bicentennial celebration of all that was great in the Australian rare coin industry.

The breadth and depth of excessively rare, high quality coins was compelling and overwhelming and was an event that is unlikely ever to be repeated. The auction made history!

Out of the glittering array of esteemed rarities, a 1920 Star Florin was chosen to appear on the front cover of the catalogue.

This is perhaps the simplest and easiest way of conveying the importance of the 1920 Star Florin to the industry.

The coin is Australia's greatest florin rarity - the rarest florin struck for circulation. One of only seven struck at the Melbourne Mint, three of which are held by private collectors, and this example with superb detail and fabulous satin surfaces.

If further accolades are required. The Numismatic Association of Australia (NAA) issued their inaugural journal in July 1985, a publication that continues to this very day. The first edition featured the 1920 Star Florin on the front cover!

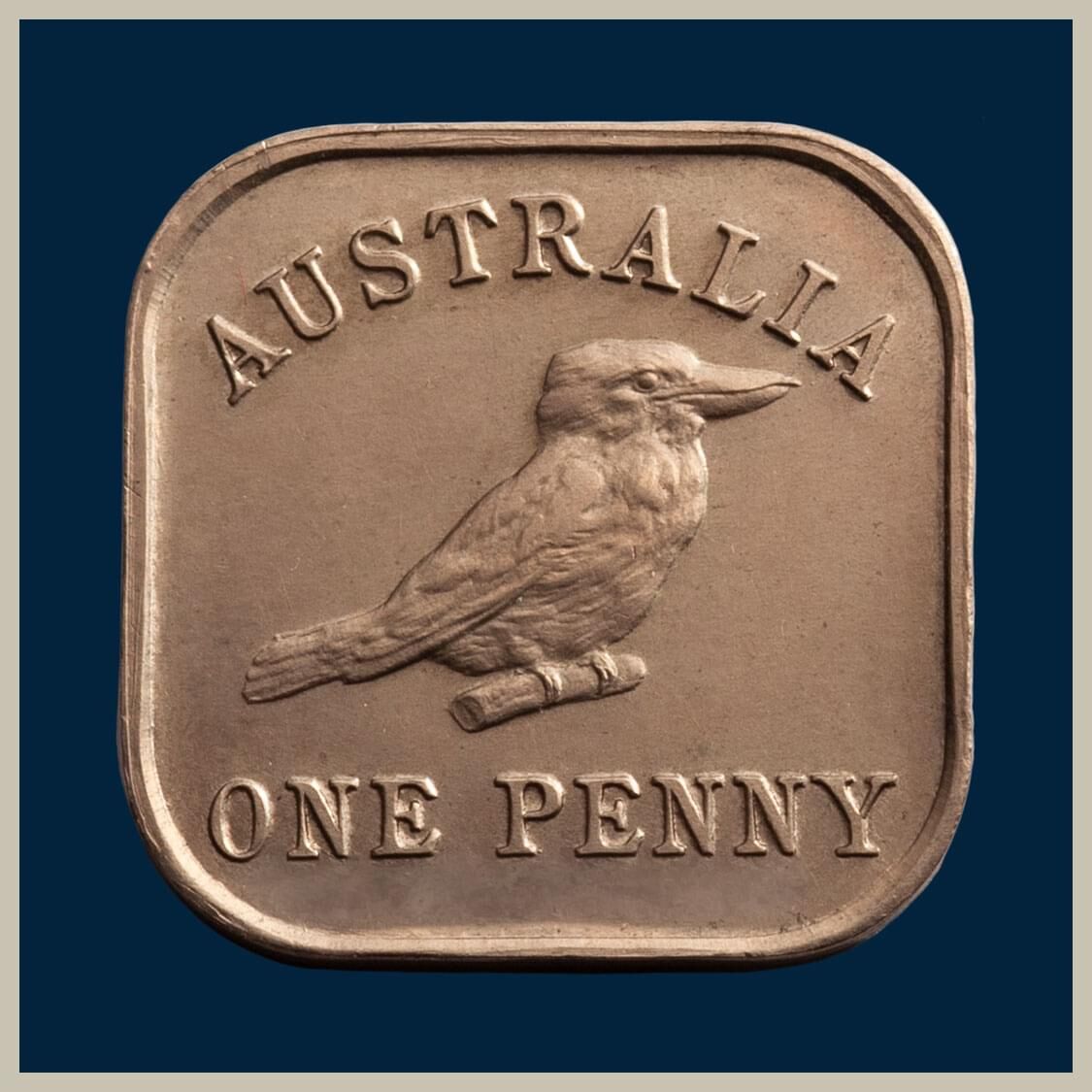

When you look at this 1813 Dump in your hand, the fields are like glass and very reflective. The design details are super-fine and clearly visible to the naked eye. And that’s a sign of a high-quality coin. This is a superior quality example of the nation’s first coin, technically ranked in the top five per cent. Over and above its quality ranking this coin has attributes that are highly prized, traits that you simply don't see in every Dump. For a start there is the 'H’ for Henshall on the reverse, the mark left by the nation’s first mint master that guaranteed his fame. On the obverse, there also is evidence of the original Spanish Dollar design from which it was created. Intact edge milling, the minting authority's ploy to prevent clipping of slivers of silver from the edges. And the elusive dot above the ‘3’ in the date 1813. A Dump that offers the lot.

Click here for more details on this Product

The buyer that pursues a top quality Dump will find the task extremely challenging. It can be years before a premium quality example comes onto the market and decades before the very best becomes available. And that statement is said in the knowledge that there are perhaps 800 Dumps, across all quality levels, available to private collectors.

The Dump with a value of fifteen pence circulated widely in the colony, the extreme wear on most Dumps evidence that they saw considerable use. The Holey Dollar being a higher valued piece, at five shillings, had a narrower band of circulation.

So, while the Dump may seem the diminutive partner of the Holey Dollar, the reality is top quality Dumps have authority. They are extremely rare, in fact far rarer than their holed counterpart in the same quality level. Official Bank of New South Wales records show that in 1820 the bank held 16,680 Holey Dollars and only 5900 Dumps. Considering that 39,910 of each were released into circulation, the figures reflect the greater circulation of the smaller denomination Dump.

Top quality Dumps are extremely rare and highly valued.

Documentation as to the method of manufacture of the Holey Dollar and Dump has never been found. It is however safe to assume that whatever machinery was employed, it was hand operated as the first steam engine did not become operational in the colony until 1815.

Likely production options were the screw press, drop hammer or hand-held punch with the drop hammer method onto a pre-heated plug generally regarded as the most likely.

There is no doubt that heat was involved in the creation of the Dump. When the disc fell out of the centre of the Spanish Dollar, it still bore the original dollar design of a four quadrant shield, housing a lion and castle in each quadrant. And the shield's cross-bars. High temperatures obliterated the original Spanish Dollar design from most examples.

Those Dumps that retain the original dollar design elements are highly prized.

The high temperatures also caused an expansion of the metal disc that fell out of the dollar. The very reason why the Dump is always larger than the hole in the Holey Dollar.

The haphazard, obliquely grooved edge milling found on the dumps indicates that a 'fiddle method' was the final step in the production process whereby a roll of Dumps was rotated under pressure against a grooved cylinder.

While no one knows the method of manufacture, history records that convicted forger and emancipist, William Henshall, was hired to create the nation's first currency, effectively our first Mint Master. He declared his involvement in the creation of the Dump - and the Holey Dollar - by inserting his initial, an 'H' for Henshall, on some - but not all - of the reverse dies of the Dump. And some - but not all - of the Holey Dollar counter stamp dies.

Amazing to think that a convicted forger created the first 'mint mark' on Australia's first coinage!

1813 Dump

struck using the A/1 dies

1813 Dump

struck using the A/1 dies

This is a classic example of the 1813 Dump.

1. The 1813 Dump circulated widely in the colony, the extreme wear on most Dumps evidence of its extensive use. The average quality Dump is graded at Fine to Good Fine, with this coin at least four grades higher at Nearly Extremely Fine / Extremely Fine. (See chart below)

2. Struck with the A/1 dies, the crown is classically well-centred and well struck, the design definition strong.

3. William Henshall inserted an 'H' into some (but not all) of the dies used during its striking. The 'H' is strong and three dimensional.

4. The denticles around the edge of the coin are evident, almost half way around. Complete denticles, all the way round, is a phenomenon that is rarely seen on the 1813 Dump.

5. The oblique milling around the edge is fully evident. (The edge milling was used as deterrent against clipping whereby the unscrupulous shaved off slivers of silver, reducing the silver content of the Dump. And making a small profit on the side.)

6. While the Holey Dollar clearly shows that it is one coin struck from another, in a less obvious way so too can the Dump. The design detail of the original Spanish Dollar from which this Dump was created is evident on the obverse. We refer to it as the under-type and it is not always present. Its existence re-affirms the origins of the Dump and is highly prized.

7. This Dump shows a 'dot' above the '3' in the date '1813'. This is almost certainly due to a pit in the die and only occurs in those coins struck with the type A/1 dies. And even then it is identified in very few type A/1 examples.

1813 Dump struck from A/1 dies, Nearly Extremely Fine / Extremely Fine and rare in this quality

When you look at this 1813 Dump in your hand, the fields are like glass and very reflective. The design details are crisp and clearly visible to the naked eye.

And that’s a sign of a high-quality coin.

This is a superior quality example of the nation’s first coin, technically ranked in the top five per cent.

Over and above its quality ranking this coin has attributes that are highly prized, traits that you simply don't see in every Dump.

For a start there is the 'H’ for Henshall on the reverse, the mark left by the nation’s first mint master that guaranteed his fame. There also is evidence of the original Spanish Dollar design from which it was created on the obverse. Intact edge milling, the minting authority's ploy to prevent clipping of slivers of silver from the edges. And there is evidence of the elusive dot above the ‘3’ in the date 1813.

Highlights of our Inventory

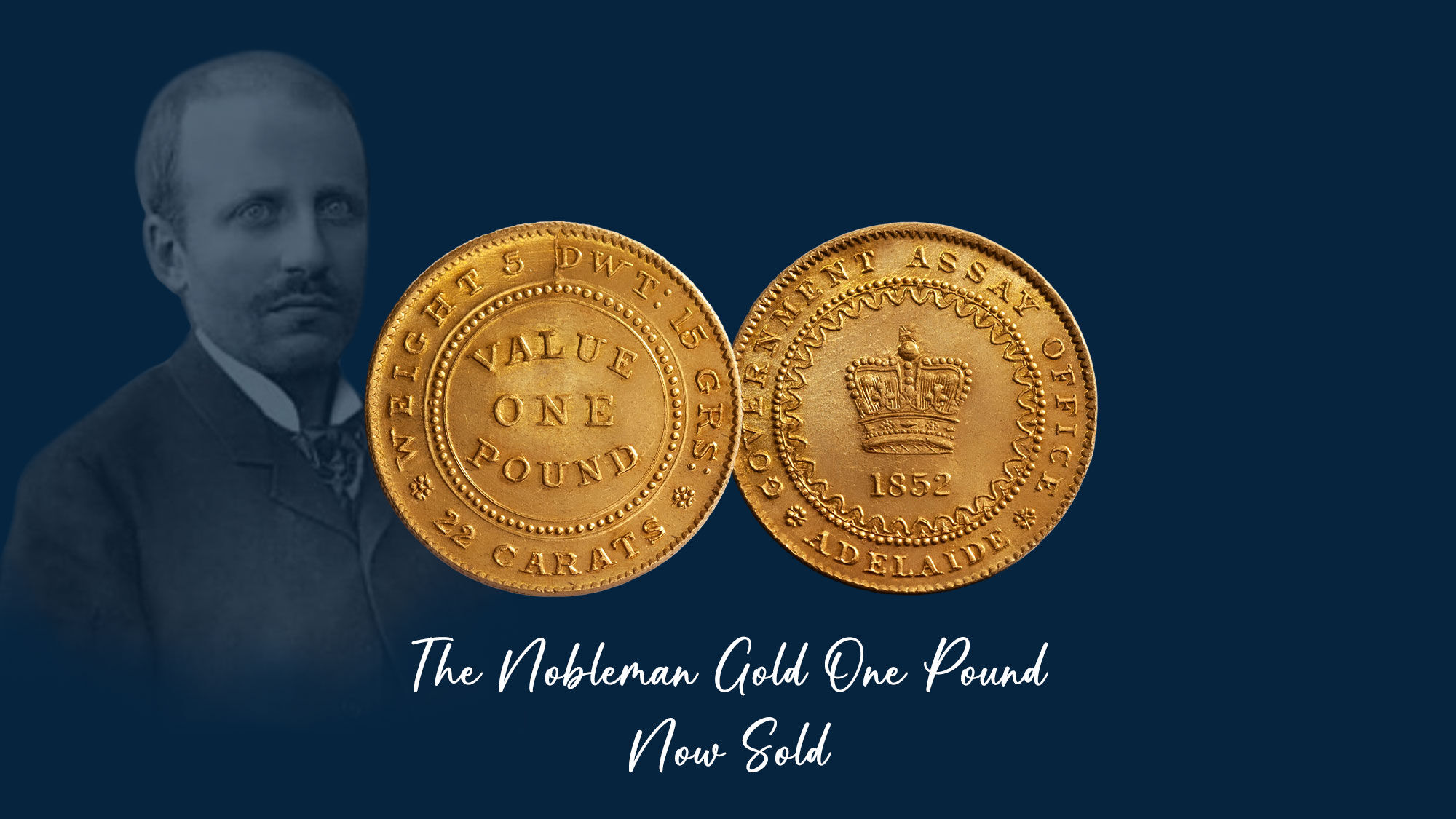

Australia’s Gold Rush of the 1850s had a major impact on Britain, stimulating trade and investment and changing the perception of Australia as a remote penal colony to a land of opportunity. The finest examples of the colony’s gold coins were pursued by Britain’s leading collectors, Montagu Hyman and John G. Murdoch. And Europe's Baron Philippe Ferrari La Renotiere whose collection was sold under the pseudonym, Nobleman. This 1852 Adelaide One Pound coin was struck in the first production run and is from the esteemed Nobleman Collection. On both counts, quality and strike, the Nobleman One Pound is genuinely exceptional and the very reason why it is universally ranked as number one. The coin has never circulated and is presented in a virtually mint state with much original bloom.

Click here for more details on this Product

When you look at a truly great circulation strike, such as the Nobleman One Pound, you can’t fail to be engaged by its state. The coin has presence and is imposing. The edges are strong. As a picture frame does to a canvass, a coin's edges enhance the visual impact by drawing the viewer's eye to the overall design. The edges also provide a sense of completion. A truly great circulation strike will also have super-fine detail and a three-dimensional design. Original mint bloom and proof-like fields.

On both counts, quality and strike, the Nobleman One Pound is genuinely exceptional and the very reason why it is universally ranked as number one. The Nobleman One Pound has never circulated and retains its mint-state condition with much original bloom.

The Nobleman One Pound is the finest example of the nation's first gold coin and was struck in the very first production run of Adelaide Pounds. And the strike, for a coin that was minted in the first run that history records was challenged with interruptions, is quite extraordinary.

The Nobleman One Pound features fine milling, the reverse crack .1mm wide. This tells us that the coin was produced not just in the first production run but it must have been struck in the first handful, for as the process continued, the crack became broader, up to .2mm in width.

The Nobleman One Pound is the coin for the buyer aspiring to the best. It will be a buyer that respects quality and recognises the importance of a documented provenance, today and into the future. A buyer that will enjoy the history of a coin that has been making headlines, both in Australia and in Britain since 1922.

No other Adelaide Pound can match this coin for its quality, its fame. And its level of public recognition.

How do you attempt to explain the brilliant state of the Nobleman One Pound? You simply can't. And that is the miracle of numismatics.

The Nobleman

Gold One Pound Type 1a

The Nobleman

Gold One Pound Type 1a

The colony of South Australia passed the Bullion Act in January 1852. The Act authorised the opening of a Government Assay Office in Adelaide to produce gold ingots that could be exchanged for banknotes at the rate of £3 11/- per ounce. Production of ingots began in February 1852.

Fielding numerous complaints about the ingots and their efficacy in solving the colony's financial crisis, the Act was amended in November of the same year to allow production of a gold coin, the Government Assay Office Adelaide One Pound. It was Australia's first gold coin.

The transition to producing a coin presented challenges for assaying staff that, while skilled in metal work, had minimal coining skills.

Finding the correct pressure balance on the dies to ensure that the design details and inscriptions were transferred accurately to both sides of the coin while at the same time producing strong edges was a major challenge that staff struggled to achieve. The milling also became an issue and was varied during the process, the belief that the fine milling may have contributed to some of their problems.

Excess pressure applied to the edges cracked the reverse die resulting in an interruption to production of the Adelaide Pound very early on in the process.

Less than fifty coins were believed struck before the crack was discovered, this coin one of them.

As the pressure was initially exerted on the edges, most Adelaide Pounds from the first run have strong edges. The downside of this pressure focus is that Adelaide Pounds from the first run show weakness in the crown.

The Nobleman One Pound has strength in the edges and a strength in the crown unseen in other examples.

Both fleur de lis are complete and three-dimensional, the pleats in the cloth are well formed. The horizontal line in the cross on the orb at the top of the crown is almost intact just tapering off on the right hand side. We also detect ermine flecks in the trim at the base of the crown. Flip the coin over and the lettering declaring its value in the central area of the design is consistently strong.

Exhibited National Museum of Australia 11 March to 24 June 2001.

Canberra's National Museum of Australia opened in 2001 as the centrepiece of the Centenary of Federation celebrations. The museum's first Exhibition, 'Gold and Civilisation', featured eight pieces from the Quartermaster Collection. The Nobleman One Pound was one of the eight and was photographed in the souvenir book.

Exhibited Museum of Victoria 19 July to 21 October 2001.

As part of the Centenary of Federation celebrations, the eight coins from the National Museum of Australia were displayed at the Museum of Victoria, Melbourne.

Exhibited Royal Australian Mint Canberra 22 February to 31 August 2005.

To celebrate the 150th anniversary of the Sydney Mint, the entire Quartermaster Collection was exhibited at the Royal Australian Mint Canberra, the Nobleman One Pound one of the highlights.

The above video of the Nobleman One Pound re-affirms its glorious, original mint state.

Collectors develop a deep connection with a coin by knowing the story behind it, when, how and why it was struck. And becoming familiar with its former owners, particularly if they are noted collectors.

When the coin is photographed in a major historical reference such as the Nobleman Catalogue the connection goes deeper. It is one thing to read about it. But seeing your coin, as featured in 1922, brings a multitude of feelings that only the true collector understands.

The Nobleman Collection was one of the ‘great’ coin holdings of its time and contained the two types of ingots, cast planchet and rolled planchet, the former eventually making its way to the Quartermaster collection via King Farouk of Egypt and USA's John J Pitman. The rolled planchet ingot was bought by the British Museum in 1922, where it still resides. The collection also included an 1852 Type Ia Adelaide Pound (this coin) and a Type II Adelaide Pound. And four Kangaroo Office Gold pieces, an 1853 One Ounce, believed to be the coin coming up in Zurich as part of the Traveller Collection, an 1853 One Quarter Ounce, a circa 1855 Gold Shilling (sold recently by Coinworks) and circa 1855 Gold Sixpence.

The historical significance of these eight pieces is reflected in their current market value of $4.25 million.

Ironically, the discovery of gold in the eastern states almost sent the colony of South Australia broke as the mass movement of population from the cities to the Victorian gold fields drained the banks of coins and brought business almost to a standstill.

As the two main pillars of national activity, labour and capital, literally walked out, prices plummeted, property plunged, mining scrip nosedived. Adelaide took on the air of a ghost town, with row after row of houses untenanted. Public works ceased, Government labourers retrenched to make them available to the private sector. So much coin was withdrawn from the banks by citizens heading for the fields that the colony's financial institutions faced closure, having insufficient coinage to meet their legally binding gold reserves that backed their banknote issues.

And whilst it may be perceived that the economy would bounce back when the diggers returned to their home state with their findings, it only exacerbated the problem. The gold boom created an excess of wealth, one that could not be put into circulation. The problem, which had plagued each colony since the early days of settlement still existed: a lack of hard currency to stimulate and underpin commerce.

The Governor of South Australia devised a two-part solution to the crisis. The first part was to ensure a ready supply of gold. Whereas the diggers were receiving 60/- per ounce in Melbourne, the South Australian Government guaranteed to pay an over-the-top price of 71/- per ounce. And went a step further by providing armed escorts to bring back the gold from the Victorian diggings.

The second part of the solution was the establishment of an Assay Office to convert gold into a useful form, the Legislative Council seeking to deflect Royal disapproval by striking gold ingots rather than sovereigns.

The ingots were not declared legal tender but were intended to form a 'currency' that would back the banknote issues of the banks as if they were gold coin at the rate of £3 11s per ounce. And be used by the banks to increase their note circulation based on the amount of assayed gold deposited.

It was a daring and contentious move. Under the Currency Act the colonies were prevented from being involved in anything affecting their currency "unless urgent necessity exists". The South Australia Government used the 'urgency' loophole in the Currency Act and passed legislation, 'The Bullion Act of 1852', that legitimised the striking of ingots and their backing of banknote issues.

It drew condemnation from the eastern states. Melbourne’s Argus condemned the Act as dangerous, radically unsound and interfering with the natural laws of commerce. But these protests were motivated by self-interest, as South Australia posed a real threat to the Victorian economy by re-directing capital and labour away from the Victorian gold fields.

The Bullion Act No 1 of 1852 has a record unique in Australian history. A special session of Parliament was convened to consider it. Parliament met at noon on the 28 January 1852. The Bill was read and promptly passed three readings and was then forwarded to the Lieutenant Governor and immediately received his assent. It was one of the quickest pieces of legislation on record, with the whole proceedings taking less than two hours.

Thirteen days after the passing of the Act, on 10 February 1852, the Government Assay office was opened. The first ingots appeared on 4 March 1852 and by the end of August 1852, over £1 million worth of gold had been received at the assay office.

The Act had its critics.

Read more

The ingots were said to be easily counterfeited. And their was no uniformity or consistency in their shape and size. The Act also compelled the banks to increase their note circulation to meet all assayed gold deposited, effectively depriving them of control over their currency issues. Three banks operated in Adelaide at the time, the South Australia Banking Company, the Union Bank of Australia and the Bank of Australasia, the latter refusing to issue notes in exchange for ingots placing a huge burden on the other two banks.

In July 1852, the business community began pressing the Government for an issue of gold coins of uniform standard and of a size and character that could be readily used as a circulating medium.

By November of the same year the Bullion Act was amended and the striking of ingots repealed. Instead the Government Assayer was instructed to strike gold pieces of 10/-, £1, £2 and £5 values.

The legislation was assented on the 23 November 1852.

Local jeweler and engraver Joshua Payne created the dies for the £1 coins, the obverse with the issuing authority, Government Assay Office Adelaide encircling a crown and the date. The reverse declared the fineness and weight encircling it's pound value.

Joshua Payne confirmed in an interview that he had created two different styles for the reverse, one with a beaded inner circle with a stylish font. The other using a scalloped inner border and a plain font. As it turns out, both dies were called upon.

The transition to producing a coin presented challenges for assaying staff that, while skilled in metal work and making ingots, had minimal coining skills.

Finding the correct pressure balance on the dies to ensure that the design details and inscriptions were transferred accurately to both sides of the coin while at the same time producing strong edges was a major challenge that staff struggled to achieve.

Excess pressure applied to the edges cracked the reverse die resulting in an interruption to production of the Adelaide Pound very early on in the process. Less than fifty coins were believed struck.

The impaired die was replaced with the second reverse die that had a different design, a scalloped inner border. A total of 24,648 coins were produced from both runs.

Only a small number of Adelaide Pounds were ever struck and very few actually circulated, the official and recorded mintage of the nation’s first gold coin, 24,648. Assaying of the one pound samples sent to London determined that the intrinsic value of the gold contained in each piece exceeded its nominal value, the vast majority were promptly exported to London and melted down.

By producing two different dies Joshua Payne clearly distinguished between those coins struck in the modest first run (referred to as Type I Adelaide Pounds). And those from the more substantial second run (referred to as Type II Adelaide Pounds).

What we know today is that less than forty Gold One Pounds from the first run are in collector’s hands. And perhaps six times that figure of the examples from the second production run. Both rare. But the first run One Pound excruciatingly rare.

The Bullion Act was intended only as a short-term solution, its operation limited to twelve months, expiring in January 1853. No attempt was made to extend it or continue the coinage after the period originally fixed.

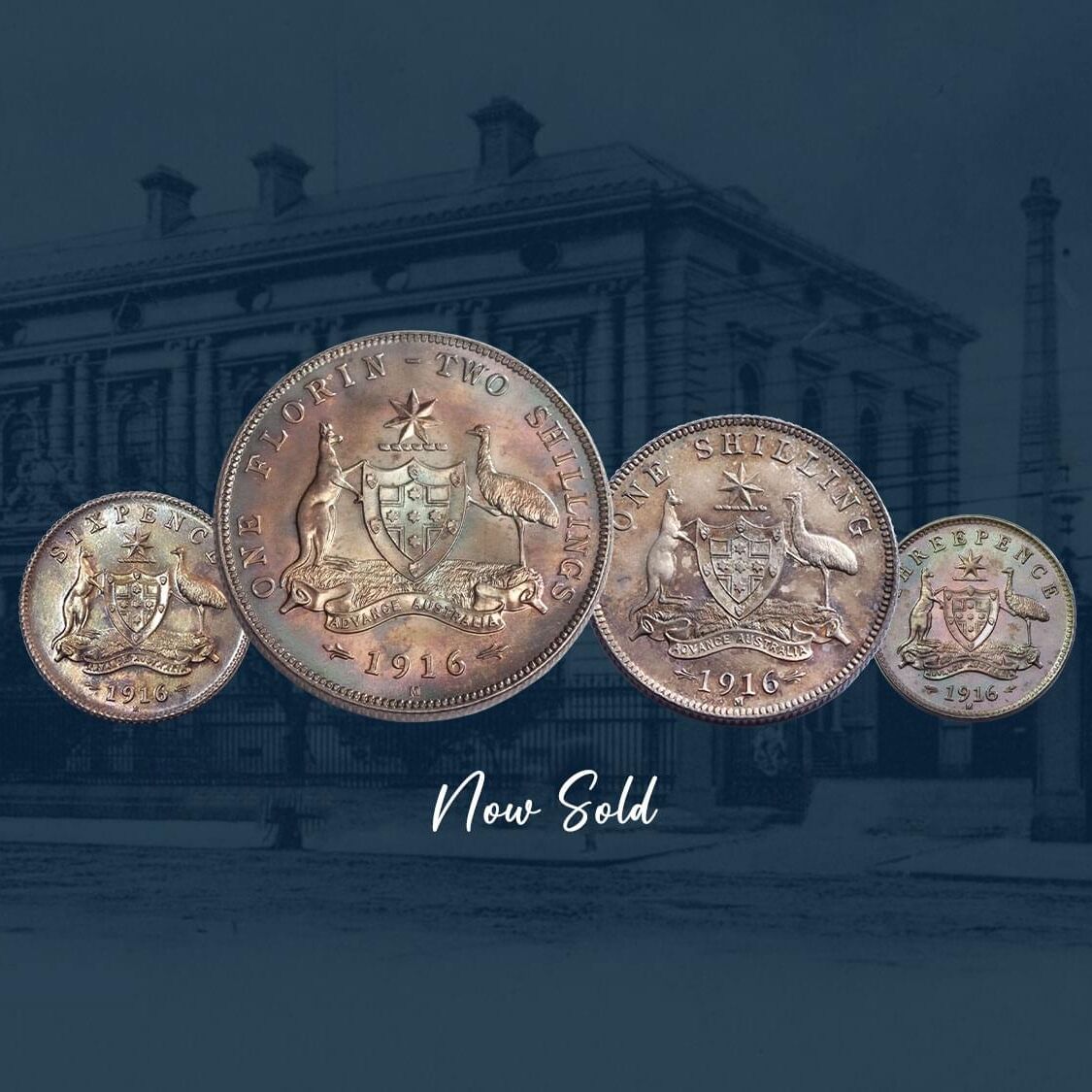

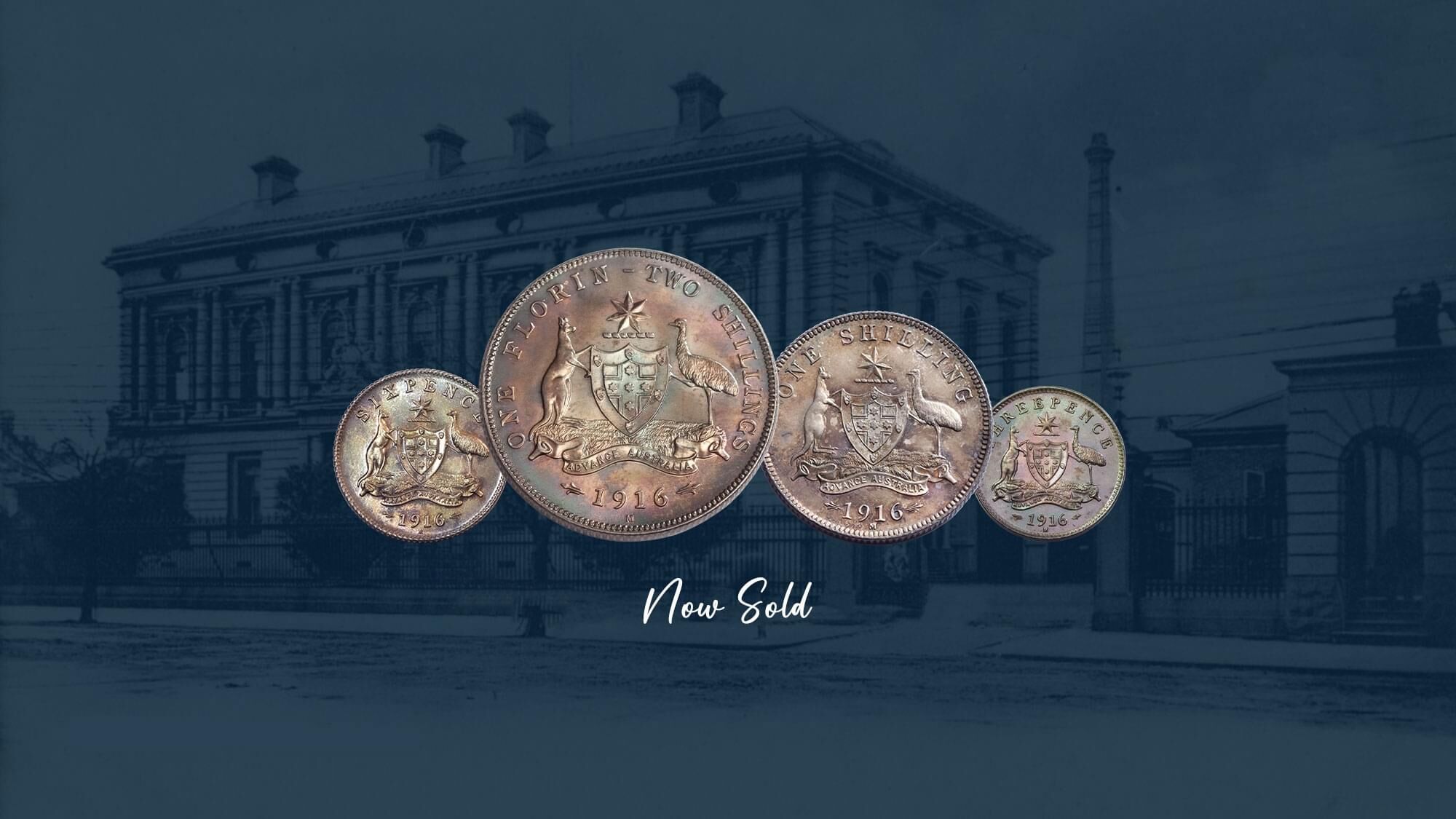

The Melbourne Mint's 1916 Presentation Set is a cultural treasure, respected as the very first issue of Australian coins made especially for collectors. Four coins make up the set, the florin, shilling, sixpence and threepence struck to specimen quality, housed in an especially crafted velvet-lined blue case. It was a big deal at the time, a celebration of the Melbourne Mint’s inaugural striking of Australia’s Commonwealth silver coinage. And it’s a big deal today with only seven original cased sets sighted at auction over the last half century. The set’s importance has been the subject of many articles, one of which penned by Dr Vince Verheyen, is provided below. Testimony to the calibre of this particular set, it was selected as the front-cover item of Monetarium Singapore's inaugural auction in 2008. An inaugural set for an inaugural auction, a masterstroke touch! And this history-making 1916 cased Specimen Set is available now.

Click here for more details on this Product

Two dates are integral to the Melbourne Mint's history and the nation’s numismatic heritage. The first is its year of opening, '1872'.

The second is '1916', when the Melbourne Mint expanded its gold coining repertoire and commenced striking silver coins for the newly formed Commonwealth of Australia.

The mint did not produce any presentation pieces to celebrate its opening in 1872, a missed opportunity for today's collectors.

That numismatic shortcoming was addressed in 1916 when the Deputy Master of the Melbourne Mint authorised the production of sixty cased Presentation Sets, a portion earmarked to sell to collectors with a 2/-3d premium over face value. Others were gifted to dignitaries.

Natural attrition has taken its toll on the original mintage and only seven cased presentation sets have been observed at auction over the last half-century.

1916 Specimen Sixpence

1916 Specimen Florin

1916 Specimen Shilling

1916 Specimen Threepence

The Melbourne Mint’s iconic 1916 cased specimen set stands out as the first Australian made presentation for collectors of the Commonwealth's coinage. There are a few things to note about the 1916 cased specimen set.

First up the royal-blue case. The case is a stamp of authority indicating that the coins are presented today as they were originally intended more than a century ago. The integrity of the set is maintained by the case. Respected numismatist and author, Dr Vince Verheyen's take on the royal-blue case supports our view that it is an integral element of the presentation. “It cannot be over-emphasised that the set must be supplied with its original case.”

The second is that the coins tone. The toning to all the coins, again gives authenticity to the set. And given the different mirror and matte finishes of the four coins, collectors should not expect the toning to be identical, a point again emphasised by Verheyen. He also added ... "I would be suspicious of any bright white specimens given their age.”

The third point to note is storage for over the years we have been asked if the coins should be stored in the case? The coins will be housed in archival quality (museum quality) coin holders and presented in a quality velvet lined tray, thereby preserving their investment value. The royal blue velvet case will be separate to the tray.

Each coin in this 1916 Presentation Set was assessed by Coinworks, and Dr Vince Verheyen as part of his research into the article on the 1916 cased Specimen Set. (See below)

We note the similarities in toning between this set and that held in the Melbourne Mint Museum.

Coin Descriptions

1916 Specimen Florin -

A stunning coin with superb colours. The obverse a gold / green. The reverse with blue on the periphery and purple on the interior. The florin is superbly struck and has fabulous detail in all the design elements with a lovely smooth matte surface on both obverse and reverse. A highly reflective coin in the light. Striations are noted on the reverse.

1916 Specimen Shilling

That so much can be written on a one shilling coin reflects the meticulous nature of the strike and the beautiful aging process that it has enjoyed. This coin is intriguing in the light. It is superbly struck with mirror surfaces between 4 o'clock and 8 o'clock in the shield area and below 'Advance Australia'. (This phenomenen was noted by Vince Verheyen in his study of the 1916 Specimen Sets.) The reverse reveals multiple striations (raised parallel lines) across the fields; with those between the scroll and date and behind the emu strongly evident. Precise edge denticles, a high rim and beautiful antique toning on both obverse and reverse characterises this shilling.

1916 Specimen Sixpence

While the florin in a 1916 Set receives most of the accolades (because of its size), the sixpence in this set almost steals the show. It is glorious. Proof-like with beautifully mirrored fields. Very well struck, the denticles on the reverse rim are unusually strong. And magnificent colours. Heavy striations on both obverse and reverse are noted. Beautifully mirrored fields on the obverse with microscopic striations confirming careful preparation of the dies.

1916 Specimen Threepence

A full brilliant mirror finish with handsome blue and pink toning. The coin is extremely well struck, noticeable in the strength of strike in the star, shield and scroll. Strong striations confirm careful preparation of the dies at the Melbourne Mint.

Early in November 1915 the Melbourne Mint was formally instructed to commence preparations for the striking of the Commonwealth's silver coinage. The silver was sourced locally from the Broken Hill mines.

It is noted that prior to 1915, the nation's silver coinage had been minted overseas at the Royal Mint London and the Heaton Mint in Birmingham.

Towards the end of November 1915, dies for the set of four denominations were sent from London.

Six weeks after the dies were shipped, the Governor of Victoria Sir Arthur Stanley K.C.M.G, struck the first circulating 1916 shilling. It was logical that the Melbourne Mint would begin striking silver coinage with the shilling denomination given its similar physical size to their familiar sovereign.

The florin was struck almost immediately after, sixpences by the middle of 1916 with the threepences finally later in the year. More than 11.5 million silver coins were released into circulation that year.

The Melbourne Mint's inaugural striking of Australia's Commonwealth coins was a momentous occasion in minting circles. The Deputy Master of the Melbourne Mint therefore decided to create a Presentation Set to record the occasion.

Each presentation set was comprised of the four silver coins of florin, shilling, sixpence and threepence, each featuring the Melbourne mint mark ‘M’ below the date 1916 and minted to specimen quality.

The set of four was housed in a handsome, velvet-lined royal blue case that had been locally sourced.

The availability of the four-coin specimen presentation set was confirmed in November 1916 when Le Souëf recorded an entry of sixty specimen sets in the Mint Museums’ cash accounts with a face value of £11 5/-.

While records show that 60 sets were produced, sixteen were sold, collectors charged 6/- for a cased set.

A further 25 sets out of the original mintage were presented to dignitaries and politicians with the precise fate of the remaining sets unknown.

What we do know is that many of the cases have been lost and many of the sets have been broken up and sold as individual coins.

We also know that others were accidentally used as circulating coins, their value irreparably reduced through wear.

Over the past 50 years we have sighted only seven sets housed in their original case of issue.

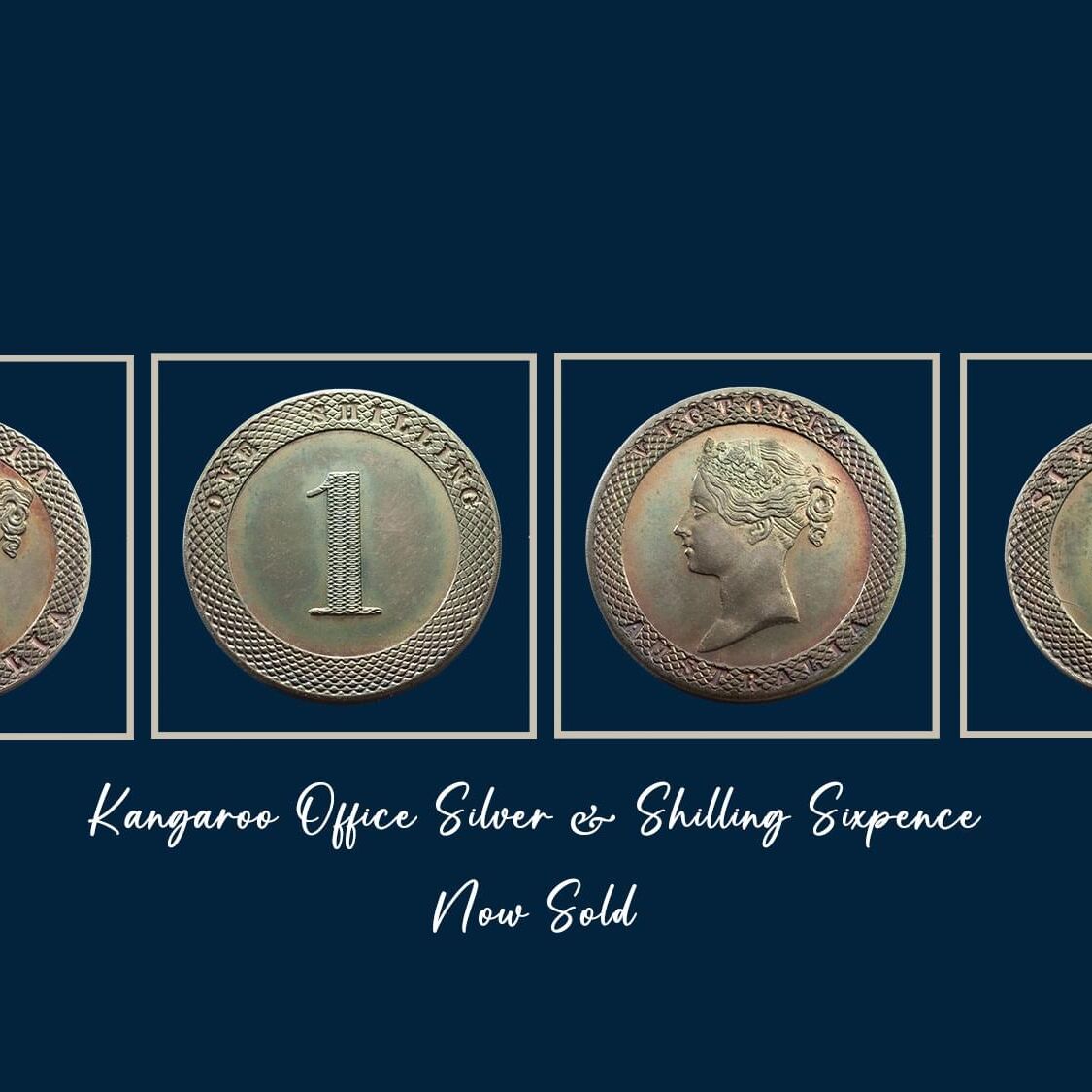

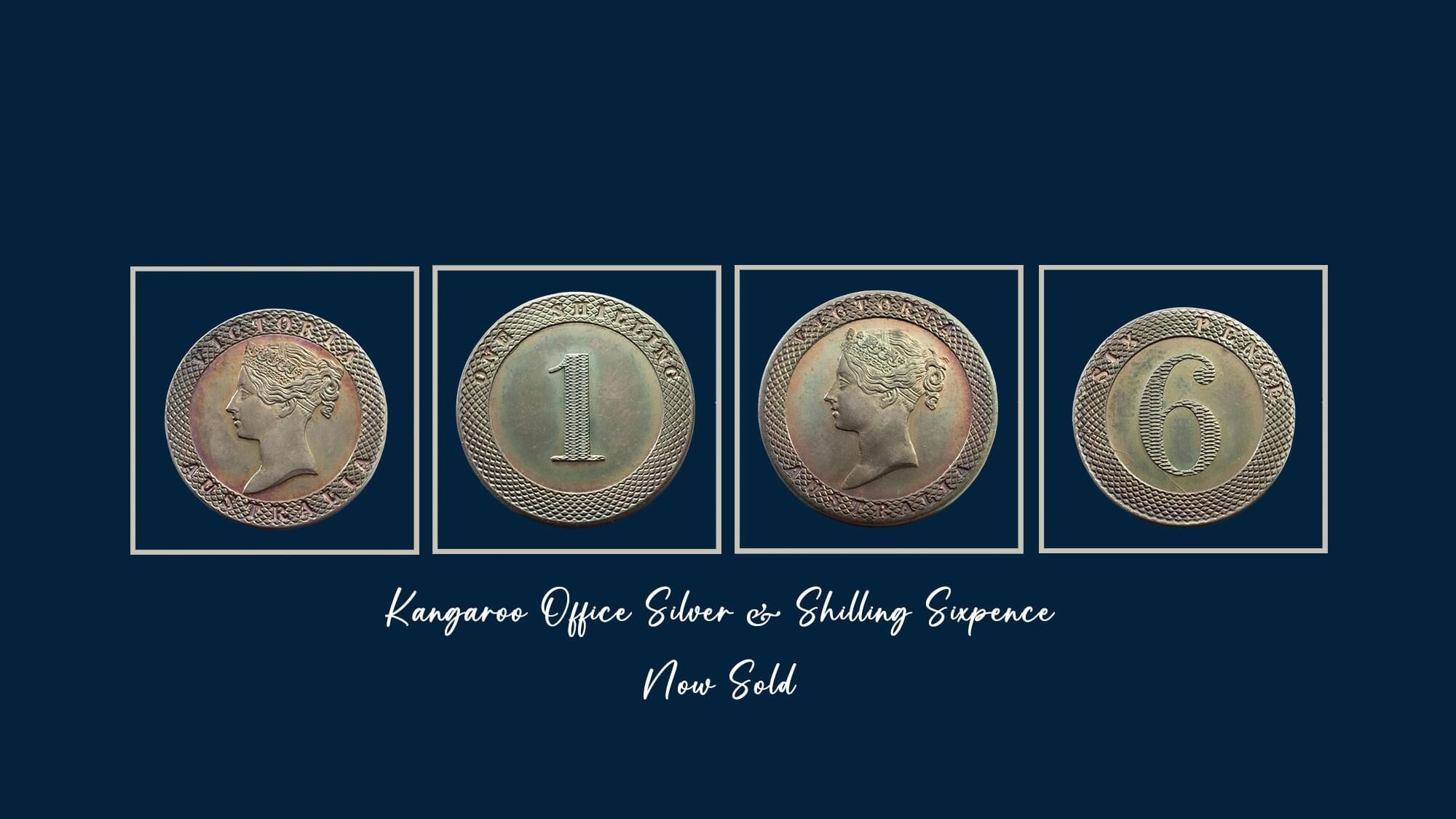

Leafing through the early John G. Murdoch Sotheby's catalogue of 1904 and those of Spink Auctions 1978, 1981 and 1989 and more recently the Quartermaster catalogue of 2009, you are in no doubt of the enormous historical and numismatic significance that the Kangaroo Office gold pieces carry. The coins are today as influential and as charismatic as they were more than a century ago. The five gold Kangaroo Office pieces offered at the Quartermaster Auction (of which this coin was one) came with an estimated low value totalling $1.125 million. And an estimated high value of $1.32 million. Only two of the five pieces sold above their 'high' estimate, the gold shilling (sold by Coinworks last week). And this coin, the gold sixpence, ex Murdoch Collection 1904. This is a pivotal moment for just one buyer. It’s a weighty decision to knock back a gold Kangaroo Office piece. Chances are you won’t be offered another one for at least a decade, maybe even two.

Click here for more details on this Product

Technical details Kangaroo Office Gold Sixpence

Reverse: A broad engine-turned rim encircles a large figure ‘6’ in the centre decoratively engraved and the words SIX PENCE incused in the rim.

Obverse: A broad raised engine-turned rim encircles a superb portrait of Queen Victoria wearing a jewelled crown, thought to be executed by William Taylor in 1860, and the words VICTORIA and AUSTRALIA incused in the rim.

(An engine-turned rim refers to a decorative pattern created by a machine-operated process whereby fine, closely spaced, criss-crossing lines are engraved into a surface. The result is a visually appealing, textured surface that adds a touch of elegance and sophistication.)

Diameter: 18.57 mm

Weight: 4.00 grams

Planchet: Thin

Edges: Plain

Circa 1860 Kangaroo Office Gold Sixpence

Circa 1860 Kangaroo Office Gold Sixpence