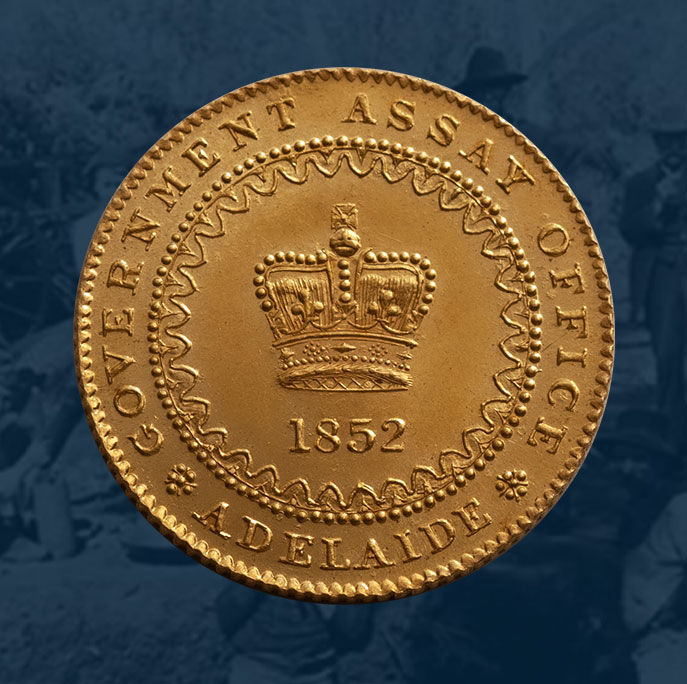

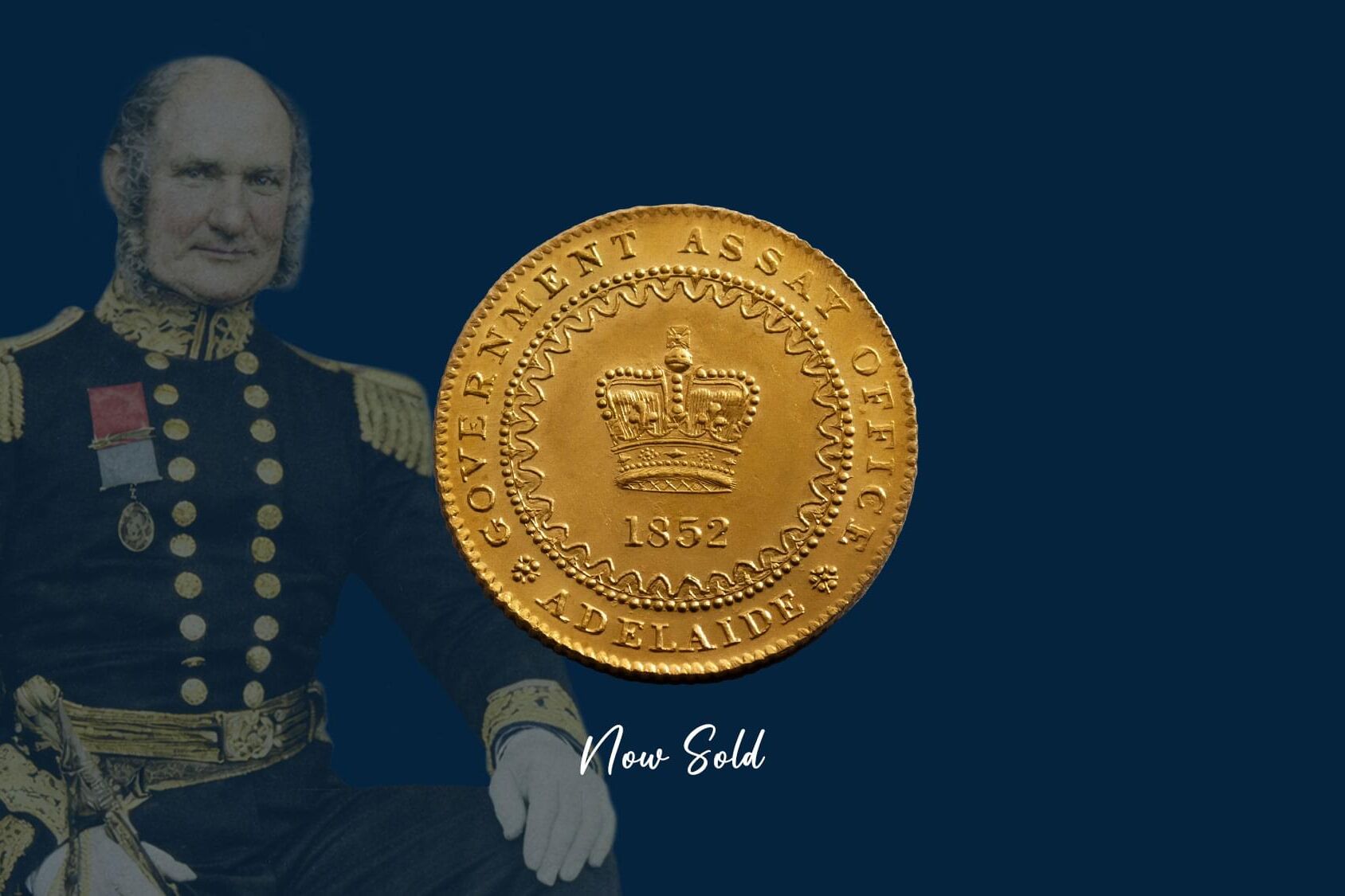

The 1852 Adelaide One Pound, the nation’s first gold coin struck at South Australia's Government Assay Office.

The discovery of significant gold deposits in Australia in 1851 created sudden wealth and stimulated immigration on a vast scale. The Gold Rush transformed the nation, economically and socially, and marked the beginnings of a modern multi-cultural Australia.

No colony was immune from the dramatic effects of the discovery of gold. Those that were rich in gold. And those, such as the colony of South Australia, that was devoid of the precious metal, its economy collapsing due to the mass exit of manpower and currency lured to the Victorian gold fields.

While enormous potential wealth was being dug out of the ground, there was no local mechanism to transform the gold into currency. Money was scarce and the colonial governments had no authority to strike coinage.

That meant gold had to be shipped to London to convert into sovereigns, involving substantial shipping costs and a round-trip time of about six to eight months. The banks monopolised gold buying on the fields, forcing artificially low prices on the diggers who were powerless to achieve the higher London price. Transport from the fields was dangerous and expensive.

There was unanimous agreement amongst the five colonies, Victoria, Western Australia, Tasmania, South Australia and New South Wales, that a gold coinage had to be locally produced, that the six month turnaround of shipping gold off to London and receiving sovereigns in exchange was unworkable. As each colony was under different pressures however, they failed to agree on the form a currency should take. And to its urgency.

Australia's first gold coin

1852 One Pound

Australia's first gold coin

1852 One Pound

The New South Wales legislature debated the establishment of an Assay Office to resolve the currency crisis. The notion was rejected, the legislators opting instead to follow protocols and petition London for the establishment of a colonial Mint. The decision was heavily influenced by the banks. While both options would present an impediment to their business, a mint was the lesser of two evils.

In the knowledge that an 'official' solution might take years, the colonial Governments of South Australia and Victoria sought a more immediate resolve, that of an Assay Office. Victoria's rumblings went nowhere. South Australia however pursued the idea with vigour, circumventing currency laws and established the Adelaide Government Assay Office.

The opening of the Adelaide Assay office required local legislation. It came in the form of the Bullion Act, enacted on 23 January 1852. The Act authorised the opening of a Government Assay Office that would produce gold ingots. While not legal tender, they could be exchanged for banknotes at the rate of £3 11/- per ounce.

Production of ingots began on 4 March 1852.

Fielding numerous complaints about the ingots and their efficacy in solving South Australia's financial crisis, the Act was amended in November of the same year and the striking of ingots repealed.

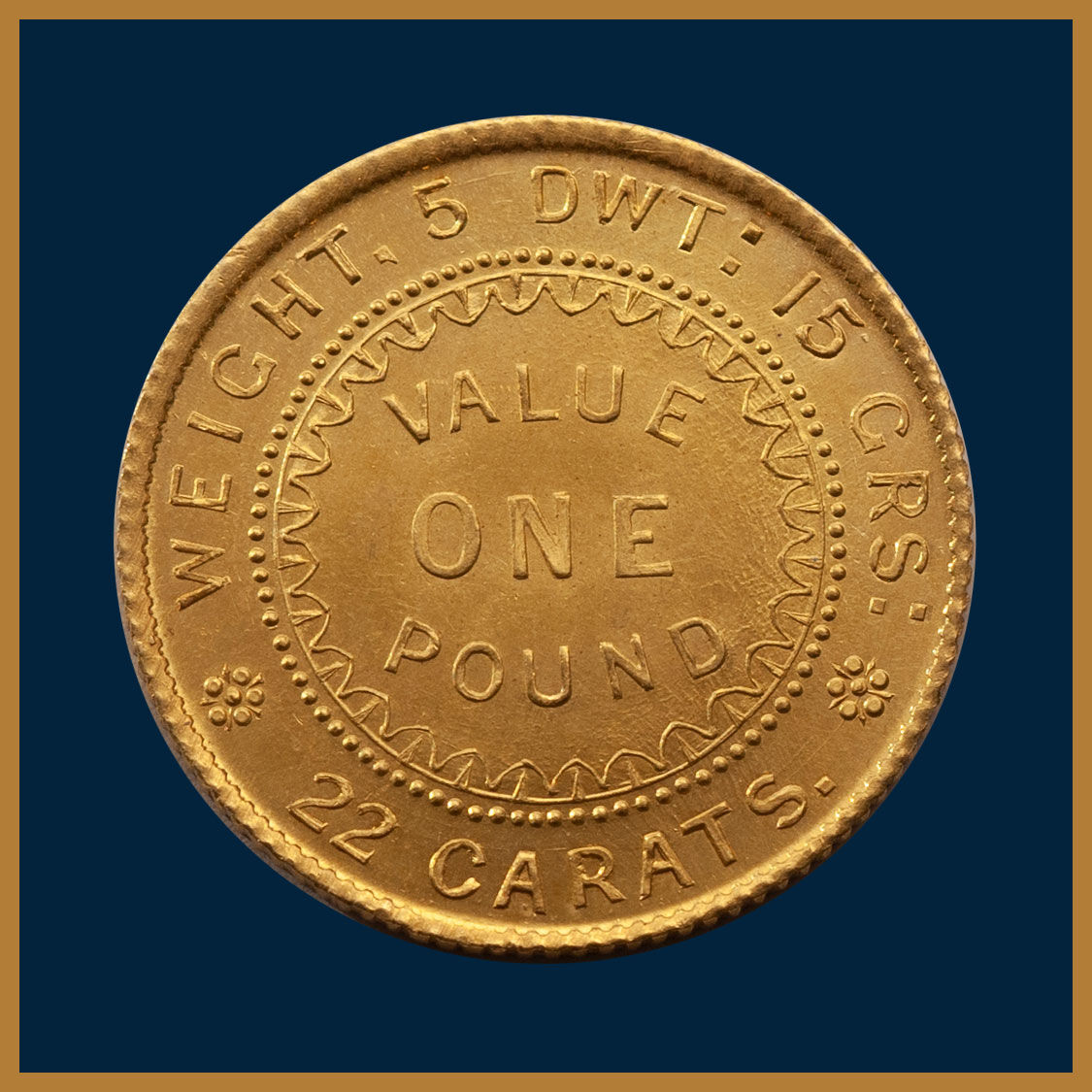

Instead the Government Assayer was instructed to strike gold pieces with a value of Ten Shillings (10/-), One Pound (£1), Two Pounds (£2) and Five Pounds (£5).

Local jeweler and engraver Joshua Payne created the dies for the nation's first gold coins. The obverse declared the issuing authority, Government Assay Office Adelaide, encircling a crown and the date, 1852, the design used continuously throughout production. The reverse declared the fineness and weight encircling it's value.

Two designs were prepared for the reverse one pound dies, the first with stylish lettering and a simple, elegant beaded inner circle. It was used in the very first production run. The second was prepared with plain lettering and a scalloped inner circle (similar to that used on the obverse) and was used throughout the second production run.

Only the One Pound coin was struck in 1852, the final mintage recorded as 24,648. No Five Pound pieces were struck in that year. The dies are however currently held in the National Collection of South Australia. Dies of the Ten Shillings and Two Pounds have never been found.

The Bullion Act was intended only as a short-term solution, its operation limited to twelve months, expiring in January 1853. No attempt was made to extend it or continue the coinage after the period originally fixed.

Adelaide Pounds from the first production run struck with a 'crown' obverse die and a 'beaded inner circle' reverse die.

The transition to producing a coin presented challenges for assaying staff that, while skilled in metal work and producing ingots, had minimal coining skills in producing pieces to a defined weight and a uniform design, the latter posing the biggest challenge.

Finding the correct pressure balance on the dies to ensure that the design details and inscriptions were transferred accurately to both sides of the coin while at the same time producing strong edges was a major challenge that staff struggled to achieve. The milling also became an issue and was varied during the process, the belief that the fine milling initially used may have contributed to some of their problems.

The first production run commenced with the 'crown' obverse die and the 'beaded inner circle' reverse die. The decision was made to apply pressure on the edges during the first run to ensure that the coin was produced with strong edge denticles and a strong legend. Excess pressure applied to the edges cracked the reverse die resulting in an interruption to production very early on in the process. Less than fifty coins were believed struck before the crack was discovered in the 'DWT' area of the legend.

As the pressure was initially exerted on the edges, most Adelaide Pounds from the first run have strong edges that enhance the visual impact by drawing the viewer's eye to the design. The downside of this pressure focus is that Adelaide Pounds from the first run may show a slight weakness in the crown.

The Adelaide Gold One Pound, struck in the first production run, is known as the Type I Adelaide Pound. With fewer than forty examples surviving from the first production run in varying degrees of quality, the Type I Adelaide Pound is Australia's greatest gold coin rarity, revered by local and international collectors.

Adelaide Pounds from the second production run struck with a 'crown' obverse die and a 'scalloped inner border' reverse die

The first production run of Adelaide Pounds was short and eventful. A cracking of the reverse die during the striking of the first fifty coins halted production.

The impaired die was replaced and production resumed, staff electing to use a die with a different design to that used in the first run, one with a scalloped inner border design. That move was profound for it clearly differentiates those coins struck in the first and second run.

In the second production run, pressure was relaxed on the edges to lengthen the die usage and re-focused on the central area of the design. The reduction in pressure on the edges meant that the edge perfection achieved in the first run of coins was simply not achievable. Most Adelaide Pounds from the second run therefore show some form of weakness in the edges, particularly in the Government Assay Office area. Occasionally the weakness is exhibited all the way round. Due to the re-focus of pressure away from the edges and to the centre of the coin, the crown design is almost always well executed with flattened areas simply due to wear.

The official recorded mintage of the nation’s first gold coin is 24,648, a relatively small number given the amount of gold deposited at the Assay Office. Very few out of the mintage actually circulated, with many of them ending up in the melting pot. Assaying of the one pound samples sent to London determined that the intrinsic value of the gold contained in each piece exceeded its nominal value. The coin therefore became the target of profiteers and were exported to London and melted down.

The Adelaide Gold One Pound, struck in the second production run, is known as the Type II Adelaide Pound. It is an iconic gold coin with perhaps two hundred and fifty available to collectors. The clear advantage of the Type II over the Type I is its affordability.

The 1852 Adelaide Gold One Pound

There is a great sense of pride and accomplishment in owning the nation’s first gold coin, the 1852 Adelaide Gold One Pound.

Compelling, with its fine design detail, the Adelaide Pound is a piece of significance, its status as the nation's first gold coin ensuring that it will never be forgotten.

And it is extremely rare with less than forty examples surviving from the first production run and perhaps two hundred and fifty from the second.

Either first or second run, the Adelaide Pound is a prized possession, an iconic gold coin revered by local and international buyers.

Market activity indicates that, in 2025, the Adelaide Pound is challenging the 1930 Penny as Australia's most sought after coin rarity.

The history of the Adelaide Assay Office and the striking of the Adelaide Gold One Pound

Ironically, the discovery of gold in the eastern states almost sent the colony of South Australia broke as the mass movement of population from the cities to the Victorian gold fields drained the banks of coins and brought business almost to a standstill.

As the two main pillars of national activity, labour and capital, literally walked out, prices plummeted, property plunged, mining scrip nosedived. Adelaide took on the air of a ghost town, with row after row of houses untenanted. Public works ceased, Government labourers retrenched to make them available to the private sector.

So much coin was withdrawn from the banks by citizens heading for the fields that the colony's financial institutions faced closure, having insufficient coinage to meet their legally binding gold reserves that backed their banknote issues.

By late 1851, genuine panic gripped those who had stayed behind as the total and complete insolvency of Adelaide looked real.

Out of desperation the Government offered a reward of one thousand Pounds for the discovery of a gold field in South Australia. None was found.

And whilst it may be perceived that the economy would bounce back when the diggers returned to their home state with their findings, it only exacerbated the problem. The gold boom created an excess of wealth, one that could not be put into circulation. The problem, which had plagued the colonies since the early days of settlement still existed: a lack of hard currency to stimulate and underpin commerce.

The Governor of South Australia devised a two-part solution to the crisis.

The first part was to ensure a ready supply of gold. Whereas the diggers were receiving 60/- per ounce in Melbourne, the South Australian Government committed to paying an over-the-top price of 71/- per ounce. And went a step further by providing armed escorts to bring back the gold from the Victorian diggings.

The second part of the solution was the establishment of an Assay Office to convert gold into a useful form as ingots, the Council seeking to deflect Royal disapproval by striking gold ingots rather than sovereigns.

The ingots were not declared legal tender but were intended to form a 'currency' that would back the banknote issues of the banks as if they were gold coin at the rate of £3 11s per ounce. And be used by the banks to increase their note circulation based on the amount of assayed gold deposited.

It was a daring and contentious move. Under the Currency Act the colonies were prevented from being involved in anything affecting the currency of the colony "unless urgent necessity exists". The South Australia Government used the 'urgency' loophole in the Currency Act and passed legislation, The Bullion Act of 1852, that legitimised the striking of ingots and their backing of banknote issues.

It drew condemnation from the eastern states. Melbourne’s Argus condemned the Act as dangerous, radically unsound and interfering with the natural laws of commerce. But these protests were motivated by self-interest, as South Australia posed a real threat to the Victorian economy by re-directing capital and labour away from the Victorian gold fields.

The Bullion Act No 1 of 1852 has a record unique in Australian history. A special session of Parliament was convened to consider it. Parliament met at noon on the 28 January 1852. The Bill was read and promptly passed three readings and was then forwarded to the Lieutenant Governor and immediately received his assent. It was one of the quickest pieces of legislation on record, with the whole proceedings taking less than two hours.

Thirteen days after the passing of the Act, on 10 February 1852, the Government Assay office was opened. The first ingots appeared on 4 March 1852 and by the end of August 1852, over £1 million worth of gold had been received at the assay office.

The Act had its critics.

The ingots were said to be easily counterfeited. And their was no uniformity or consistency in their shape and size. The Act also compelled the banks to increase their note circulation to meet all assayed gold deposited, effectively depriving them of control over their currency issues. Three banks operated in Adelaide at the time, the South Australia Banking Company, the Union Bank of Australia and the Bank of Australasia, the latter refusing to issue notes in exchange for ingots placing a huge burden on the other two banks.

In July 1852, the business community began pressing the Government for an issue of gold coins of uniform standard and of a size and character that could be readily used as a circulating medium.

By November of the same year the Bullion Act was amended and the striking of ingots repealed. Instead the Government Assayer was instructed to strike gold pieces of 10/-, £1, £2 and £5 values.

Local jeweler and engraver Joshua Payne created the dies for the £1 and £5 coins, the obverse with the issuing authority, Government Assay Office Adelaide encircling a crown and the date. The reverse declared the fineness and weight encircling it's pound value. Only the £1 coin was struck. (No dies of the 10/- or £2 have ever been discovered.)

The Bullion Act was intended only as a short-term solution, its operation limited to twelve months, expiring in January 1853. No attempt was made to extend it or continue the coinage after the period originally fixed.

On the 26 November notice was given that six hundred Adelaide One Pounds were delivered to the South Australian Banking Company, of which one hundred were sent to London.

Only a small number of Adelaide Pounds were ever struck and very few actually circulated, the official and recorded mintage of the nation’s first gold coin, 24,648. Assaying of the one pound samples sent to London determined that the intrinsic value of the gold contained in each piece exceeded its nominal value, the vast majority were promptly exported to London and melted down.

History records that disaster struck during the early stages of production of the 1852 Adelaide Pound. Die-maker and engraver Joshua Payne confirmed that staff had struggled to find the correct pressure levels to exert on the dies to execute a strong overall design.

The first production run commenced with the 'crown' obverse die and the 'beaded inner circle' reverse die, the decision made to apply pressure on the edges to ensure that the coin was produced with strong edge denticles and a strong legend.

The pressure proved excessive. Only a small number of coins (less than 100) were produced before a crack developed in the edge of the reverse die, forcing an interruption to minting.

The impaired die was replaced and production resumed using a second reverse die that had a different design, a scalloped inner border. A total of 24,648 coins were produced from both runs.

By producing two different dies Joshua Payne clearly distinguished between those coins struck in the modest first run. And those from the more substantial second run.

What we know today is that less than forty Type I Gold One Pounds are in collector’s hands. And perhaps six times that figure of the Type II examples. Both rare. But the Type I One Pound excruciatingly rare.

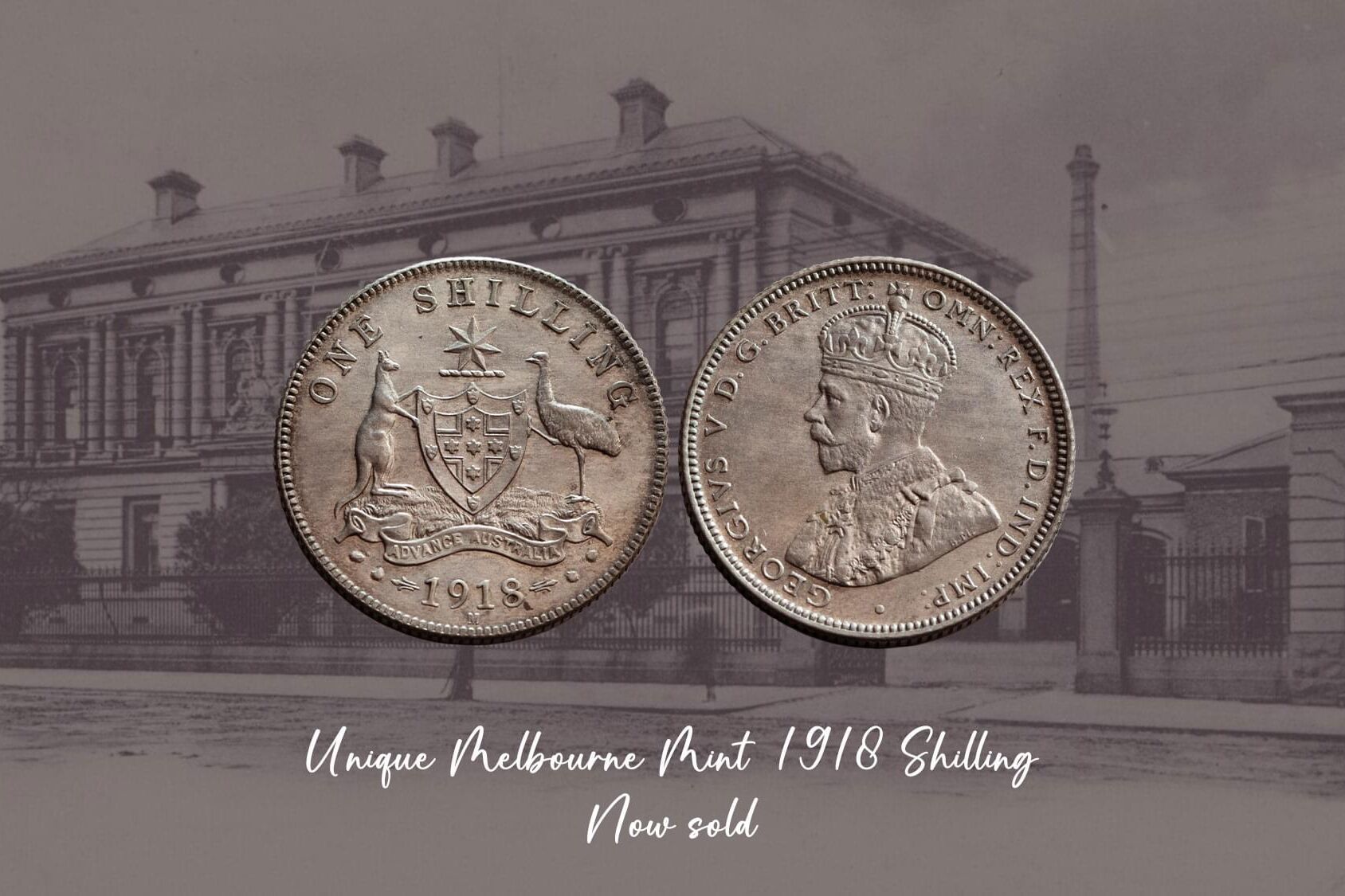

Highlights of Coinworks Inventory

© Copyright: Coinworks