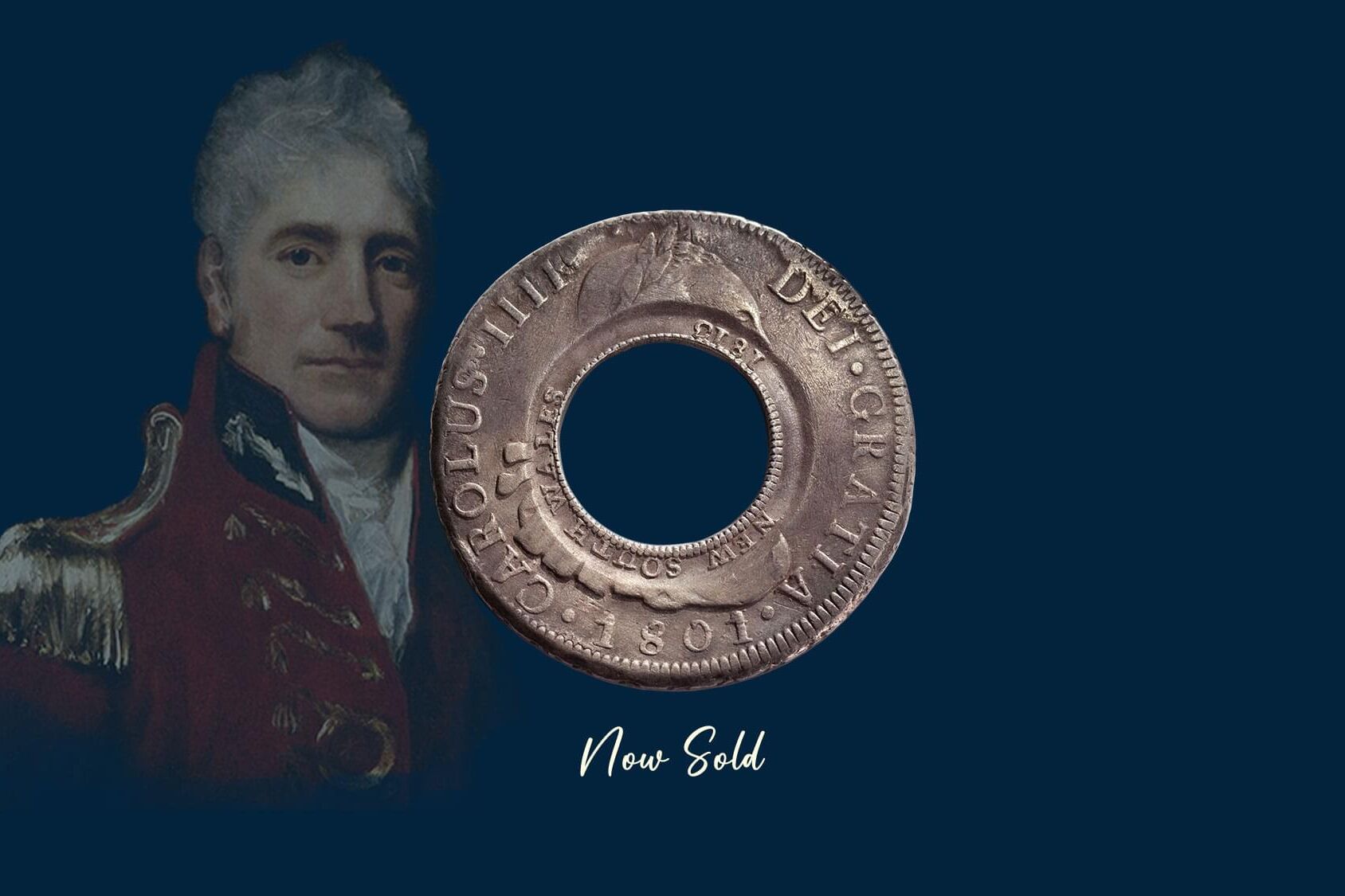

The Holey Dollar is the nation’s first coin, minted in 1813 by order of Governor Lachlan Macquarie.

The Holey Dollar is the nation’s first coin, minted in 1813 by order of Governor Lachlan Macquarie.

The issuing of Australia’s first coinage symbolised the changing dynamics of the penal colony of New South Wales. The colony had started out in 1788 as a jail, a repository for convicts, under the governorship of Captain Arthur Phillip. It had emerged some twenty-five years later as a thriving economy requiring a formal medium of exchange to support a burgeoning commercial hub.

As Macquarie had no access to metal blanks to create his currency, he improvised and acquired 40,000 Spanish Silver Dollars as a substitute.

To make his new coinage unique to the colony, and to inhibit their export, he employed emancipated convict William Henshall to cut a hole in each silver dollar.

Each holed silver dollar was then counterstamped on both sides, around the edge of the hole. On one side, the date 1813 and the issuing authority of New South Wales. And on the other side, the value 'Five Shillings' with some decorative embellishments of a fleur de lis, a double twig of six leaves and a tiny 'H' for Henshall at the junction of the twigs.

The application of the counterstamps is the point at which the holed silver dollar became the 1813 Holey Dollar, the nation's first locally made coinage. Prior to that, it was just a Spanish coin with a hole in it!

While the original intention was to create 40,000 Holey Dollars from 40,000 silver dollars, spoilage and the despatch of samples back to Great Britain saw a slightly reduced number of Holey Dollars - 39,910 - released into circulation.

Today there are approximately two hundred Holey Dollars held by private collectors with perhaps one hundred held in museums. As a cultural and financial icon, the appeal of the Holey Dollar extends far beyond numismatics, driven by its immense historical significance and tangible connection to a foundational moment in Australian history ... the creation of our first coinage.

Owning a Holey Dollar is about indulging in an experience, a fusion of history and prestige. And its about savouring the moment. It has been the inspiration and aspiration of many. Think Macquarie Bank and its logo! Museums, the world over. Historians, collectors, investors, both local and international.

Valuing a Holey Dollar in four steps. 1 - Date. 2 - Mint. 3 - Quality. 4 - Counterstamps.

Most coins are created from a metal blank onto which a decorative pattern is stamped in a process that produces thousands (millions) of uniformly struck coins, each featuring the same design.

Valuing them is pretty simple: consideration given to the wear due to circulation (the coin's quality), how well the strike was executed and their rarity at that level of quality.

The 1813 Holey Dollar began its life as another coin, a Spanish Silver Dollar. Valuing a Holey Dollar, therefore, requires an assessment of that original Spanish Silver Dollar coin.

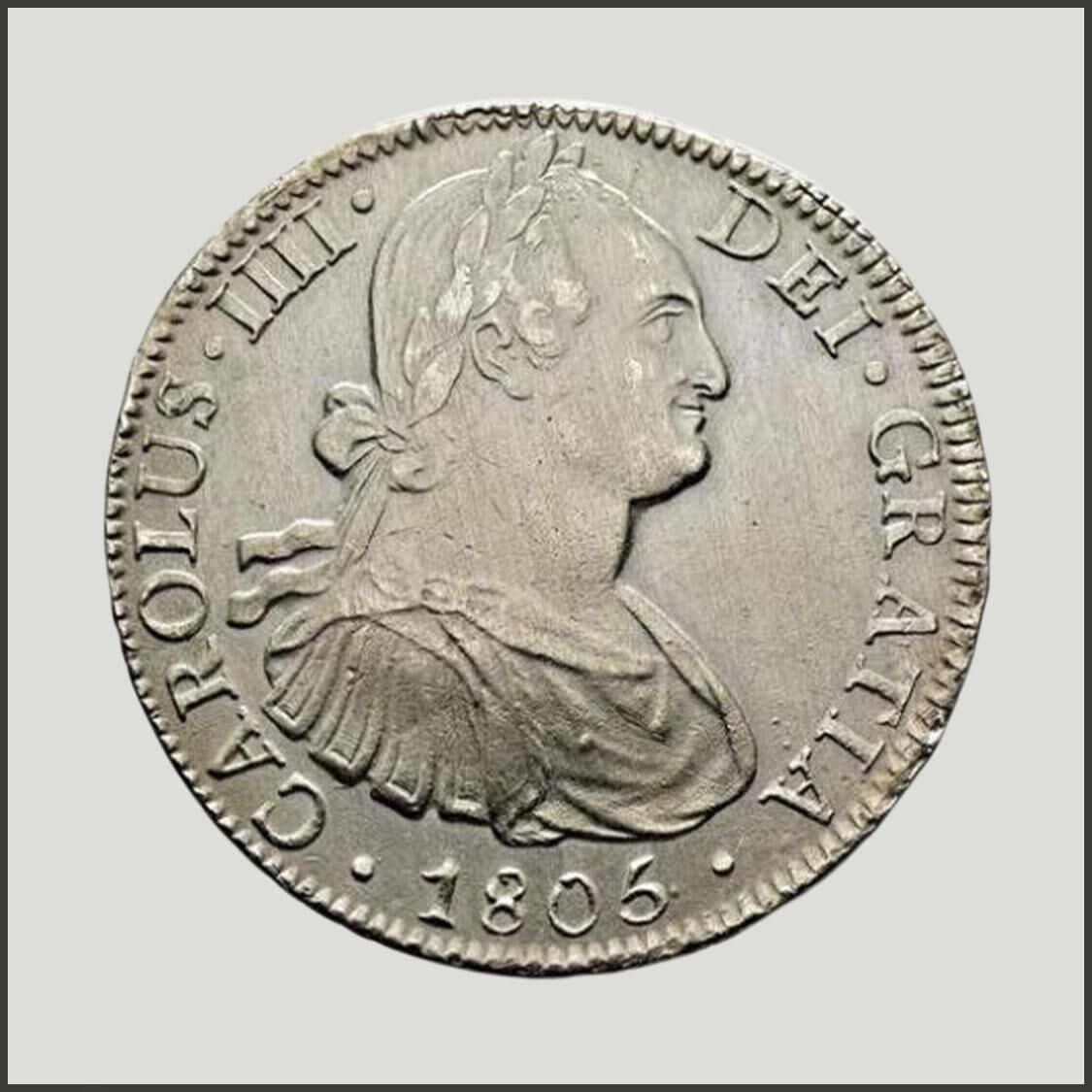

1. What date is on the Spanish Silver Dollar? Who was the Spanish King at the time? As the dates varied, so too could the reigning Spanish monarch, Ferdinand VI, Charles III, Charles IV or Ferdinand VII. Death, abdication or dethronement the three instigators of change. Holey Dollars featuring the portrait of Charles IV are the most readily available, followed by Charles III, Ferdinand VII with the Ferdinand VI Holey Dollar known by just two examples.

2. Where was the dollar minted? In Spain or one of the Spanish colonies in South America, Mexico, Peru or Bolivia? The 40,000 dollars sourced by Macquarie came from various countries, each with a different mark to identify the issuing mint. Holey Dollars created from silver dollars issued by the Mexico Mint are the most readily available, followed by the Lima Mint in Peru, Potosi Mint in Bolivia, with the Madrid Mint unique in private hands.

3. Was the dollar well used or did it arrive in the colony relatively unscathed? Collectors are quality focused. It is the nature of the beast! Of particular interest with Holey Dollars, the quality relative to the date in which it was struck. The point here is that the earlier the date on the silver dollar (1789 versus 1807 let's say), the greater the chance of the coin circulating before Henshall grabbed it in 1813 and cut a hole in it. (Twenty four years in the case of the 1789 silver dollar, six years in the case of the 1807.)

4. Valuing a Holey Dollar also gives consideration to the counterstamps, the application of which converted a holed Spanish coin into Australia's first! Are they worn? And how do you rate William Henshall's job of cutting and over-stamping the holed silver dollar? The quality of the counterstamps reflects the extent of usage of the Holey Dollar. The finesse of the counterstamps reflects how well Henshall executed the strike. Is the hole centered? Are the counter-stamps nicely balanced with the coin design or are they 'all over the shop'? Also noted that, as with the Dump, some counterstamp die combinations are rarer than others.

A major pleasure for owners is appreciating the story behind their Holey Dollar: the date, the monarch, the mint, the political statements. And its usage. As each Holey Dollar is unique, each coin has its own story to tell, so the narrative becomes uniquely yours. When you buy a Holey Dollar you just don't buy a coin. You buy the story and the experience.

Step 1 - the date and monarch depicted on the Spanish Dollar.

Forty thousand Spanish Silver Dollars were imported by Governor Lachlan Macquarie from the East India Company to convert into forty thousand Holey Dollars, the nation's first circulating currency.

And those dollars came with different dates. And as the dates varied, so too could the reigning monarchs.

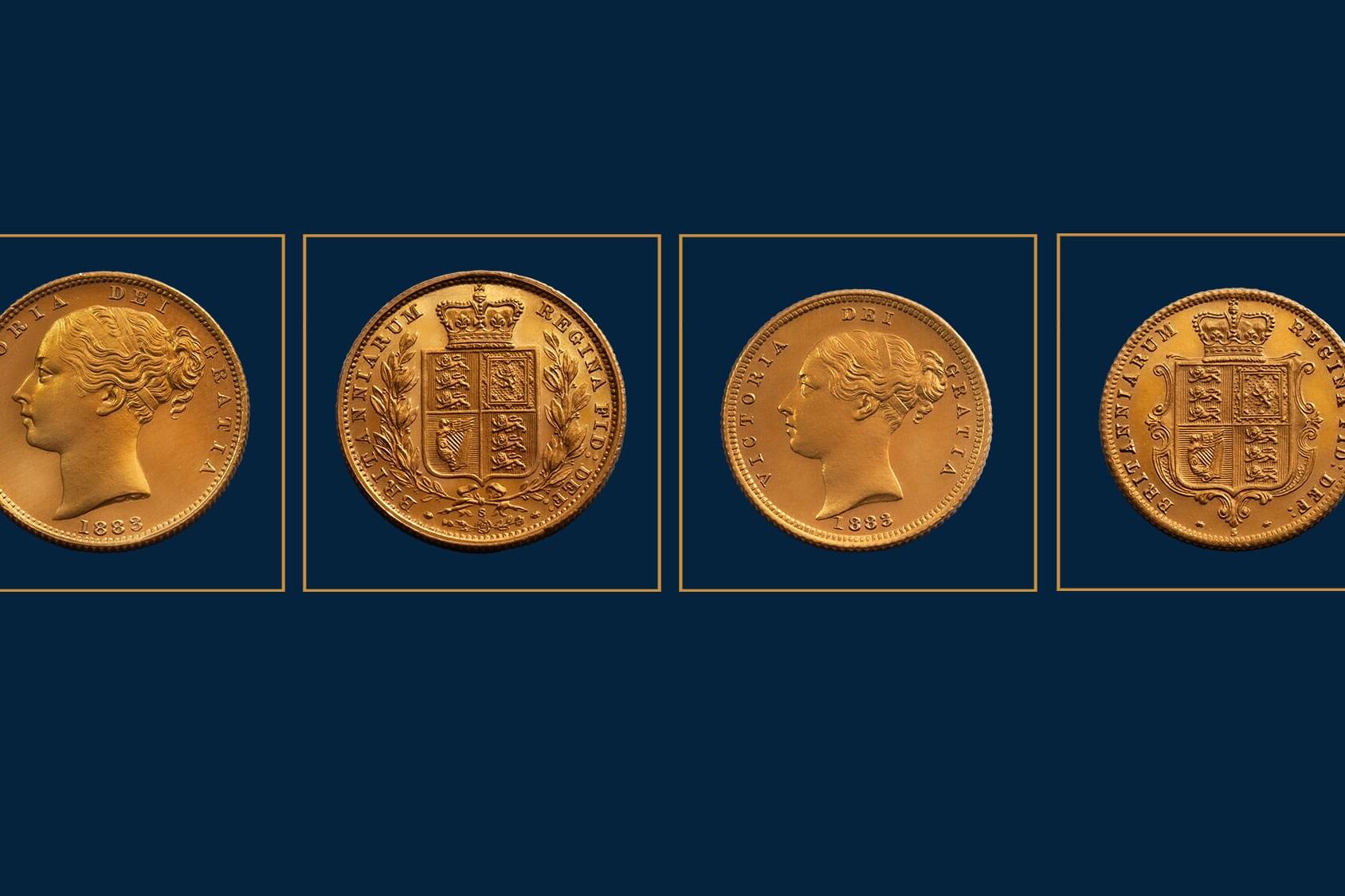

Ferdinand VI reigned from 1746 to 1759. Charles III, reigned from 1759 to 1788. Charles IV was the reigning monarch from 1788 to 1808 and Ferdinand VII endured a disrupted reign, 1808 and again between 1814 and 1833.

And as each king ascended the throne, the design of the dollar was re-created with a re-styled legend and a re-styled portrait to record the new reigning monarch.

Note the dates on the Holey Dollars below, from left to right, 1757, 1788, 1789, 1790, 1802, 1805, 1809 and 1810. Also note the changing legends of Ferdinand VI, Charles III, Charles IV, Charles IIII and Ferdinand VII. And the changing portraits.

The Holey Dollar is a story.

Its narrative, is as much about Australian history as it is about European history, charting the changing Spanish monarchs, Ferdinand VI, Charles III, Charles IV and Ferdinand VII. And reflecting the associated political and social turmoil that so often occurs when a monarch dies or abdicates. (Coinage has always been politicised.)

Holey Dollars are classified into types based on the legend and portrait of the monarch depicted on the original Spanish Silver Dollar. A special classification is given to those Holey Dollars created from dollars minted in Spain (in Madrid or Seville) as the design varies from those struck in the colonies, the differences occurring in the legend, portrait and the shield. They are referred to as Continental Dollars. The dollars struck in the Spanish colonies are referred to as Colonial Bust Dollars. (Photo Gallery at the end of article shows the design differences. )

There are eight distinct types of Holey Dollars as photographed and detailed below. The number noted as 'availability' reflects the quantity of that type available to collectors and excludes those specimens held in museums.

Type 1 - Ferdinand VI

Features the legend and portrait of Ferdinand VI.

Availability: 2

Type 2 - Charles III

Features the legend and portrait of Charles III.

Availability: 22

Type 3 - Charles III Deceased

Features the legend and portrait of the deceased King Charles III, issued during the reign of

Charles IV.

Availability: 2

Type 4 - Charles III on Charles IV

Features the portrait of the deceased King Charles III and the legend of the reigning monarch Charles IV.

Availability: 8

Type 5 - Charles IV

Features the legend and portrait of Charles IV.

Availability: 129

Type 5A - Charles IV Continental

Struck from a Continental Silver Dollar, featuring the legend and portrait of Charles IV.

Availability: 1

Type 6 - Ferdinand VII

Features the legend and portrait of Ferdinand VII.

Availability: 13

Type 7 - Hannibal Head

Features the legend of Ferdinand VII and an imaginary portrait of the monarch referred to as the 'Hannibal Head'.

Availability: 2

Step 2 - the Mint at which the Spanish Dollar was issued.

The Spanish Silver Dollar was the coin that ruled the world.

Beginning with Columbus in 1492 and continuing for nearly 350 years, Spain conquered and settled most of South America, the Caribbean, and the south west of America.

It was however, the silver rich continent of South America that became Spain’s treasure trove, bank rolling its ascendancy as a world power.

In 1536, Spain established its first colonial mint in Mexico. It was by far the most lucrative of the Spanish mints, coining more than 2 billion dollars’ worth of silver pieces over a 300 year period (1536 – 1821).

The Lima and Potosi Mints came on board in 1568 and 1573 respectively. Guatemala and Colombia some years later.

As the Mexico Mint was a prolific producer of silver coinage approximately eighty per cent of Holey Dollars were converted from Mexico Mint Silver Dollars. Of the remaining mints, ten per cent pertain to Lima and eight per cent to Potosi. Only six specimens have ties to the mints in Spain (four struck in Madrid and two at Seville). Five are held in museums and one only available to collectors, the Madrid Holey Dollar. (During the latter part of the 18th century and early 19th, silver in Spain was a status symbol and silver pieces were hoarded, rarely spent. A Holey Dollar punched out from a silver dollar minted in Spain is an extreme rarity.)

Only one Holey Dollar has ties to the mint in Guatemala, held by a Museum in Quebec Canada. To this day no Holey Dollars have been found with ties to Chile or Colombia.

1813 Holey Dollar created from a

Mexico Mint

1788 Spanish Silver Dollar

1813 Holey Dollar created from a

Madrid Mint

1802 Spanish Silver Dollar

1813 Holey Dollar created from a

Potosi Mint

1807 Spanish Silver Dollar

1813 Holey Dollar created from a

Lima Mint

1808 Spanish Silver Dollar

Mint mark of the Mexico MInt in the reverse legend

Mint mark of the Madrid Mint in the reverse fields

Mint mark of the Potosi Mint in the reverse legend

Mint mark of the Lima Mint in the reverse legend

Mint mark Mexico Mint, 'M' with a small circle above it, enlarged.

Mint mark Madrid Mint,

'M' underneath a crown, enlarged.

Mint mark Potosi Mint,

PTS monogram, enlarged.

Mint mark Lima Mint,

LMAE monogram, enlarged.

THE MEXICO MINT

1813 Holey Dollar created from a

Mexico Mint

1788 Spanish Silver Dollar

Mint mark of the

Mexico Mint in the reverse legend

Mint mark Mexico Mint, 'M' with a small circle above it, enlarged

THE MADRID MINT

1813 Holey Dollar created from a

Madrid Mint

1802 Spanish Silver Dollar

Mint mark of the Madrid Mint

in the reverse fields

Mint mark Madrid Mint

'M' underneath a crown, enlarged

THE POTOSI MINT

1813 Holey Dollar created from a

Potosi Mint

1807 Spanish Silver Dollar

Mint mark of the Potosi Mint

in the reverse legend

Mint mark Potosi Mint

PTS monogram, enlarged.

THE LIMA MINT

1813 Holey Dollar created from a

Lima Mint

1808 Spanish Silver Dollar

Mint mark of the Lima Mint

in the reverse legend

Mint mark Lima Mint

LMAE monogram, enlarged.

Step 3 - the quality of the Spanish Dollar.

If a Holey Dollar had been struck from a bright and shiny brand-new piece of silver, we would accept that some might survive today relatively unscathed.

The Holey Dollar, however, was struck from a Spanish Silver Dollar, a commodity that was far from shiny and brand-new. In the eighteenth-century Spain ruled the world and the Spanish Silver Dollar dominated trade. It was an international currency and medium of exchange the world over.

Macquarie would not have set any quality parameters on his shipment. Most of the coins imported by Macquarie would therefore have been well worn. A study of the quality of the surviving Holey Dollars confirms the fact.

Of the one hundred and seventy nine Holey Dollars held in private hands, more than fifty per cent (about ninety Holey Dollars) were created from well circulated silver dollars, coins where the general outline of the design is recognisable but the significant parts, the fine detail, is worn away. At least ten per cent of these are so denuded of detail that they look like a tap washer.

As with all coins struck as circulating currency, once a collector introduces quality standards into a selection process, the pool of available examples substantially reduces.

Quality is a refinement on rarity. And quality increases the value of a commodity due to its reduced availability.

About fifteen per cent of the privately held Holey Dollars (less than thirty examples) were created from high quality silver dollars where high quality is technically defined as Good Very Fine to Uncirculated. (See Photo Gallery at end of article.)

The very top examples (Extremely Fine to Uncirculated) are known by about ten coins. And only one Holey Dollar survives today in Uncirculated quality.

Six of the best Holey Dollars are shown here, their quality and their ranking.

Ranking: One

Quality: Uncirculated

Ranking: Two

Quality: About Uncirculated

Ranking: Three

Quality: Good Extremely Fine

Ranking: Four

Quality: Good Extremely Fine

Ranking: Five

Quality: Extremely Fine

Ranking: Six

Quality: Extremely Fine

Step 4 - the counterstamps, quality and finesse.

No one really knows how the Holey Dollar was manufactured. Documentation as to the method has never been found. It is safe to assume that whatever machinery was employed, it was hand operated as the first steam engine did not become operational in the colony until 1815.

Likely production options were the screw press, drop hammer or hand-held punch with the drop hammer method considered the most likely. And it is assumed that the centre was cut out and the holed dollar overstamped, in two separate operations.

Quality of the counterstamps - the wear to the counterstamps indicates the degree of circulation of the Holey Dollar. Most counterstamps show only slight usage. The reason being that the Holey Dollar, as a high denomination coinage (Five Shillings) was stored by the Bank of New South Wales as backup for their banknotes and underwent minimal circulation.

Great force had to be exerted on the Spanish Silver Dollar to punch out the centre hole and, as a consequence some Holey Dollars are found dished, exposing the convex side of the coin and the counterstamps, to extraordinary wear.

The finesse of the counterstamps - a study of the surviving Holey Dollars reveals that Henshall's application of the counterstamps was wildly random, that the holed dollar was not placed in a particular position between the dies. And it obviously didn't matter which side of the holed dollar was facing up. The strike lacked a definite pattern or predictability, as shown by the position of the counterstamps in the Holey Dollars shown above.

Our slideshow features two Holey Dollars that are stand out pieces by virtue of their counterstamps. The first a Holey Dollar created from a 1788 Charles III Mexico Mint silver dollar, the counterstamps in perfect alignment with the design of the coin, and extremely rare as such. And the second, a Holey Dollar created from an 1805 Mexico Mint silver dollar, the counterstamps Uncirculated. A miracle coin for the original dollar is also Uncirculated.

An examination of the counterstamps

Four standard counterstamp dies have been identified. 'New South Wales' '1813' is deemed to be the obverse die and there are two variations, designated Die I and Die II. 'Five Shillings' is deemed the reverse die and there are also two design variations, designated Die A and Die B.

They appear in the following combinations.

• Die I with Die A (41 per cent)

• Die I with Die B (27 per cent)

• Die II with Die B (32 per cent)

It is noted that there are no Holey Dollars with the Die II and Die A combination.

Also noted these standard counterstamp die combinations appear in all but five Holey Dollars. Information is available on request on the non-standard dies used on the five known Holey Dollars (designated III, C and D).

The identification of the dies takes the following format:

Die / Number between 1 and 12 : Die / Number between 1 and 12

The first die cited is that which appears on the Holey Dollar obverse (I, II, A or B), the second die is that appearing on the Holey Dollar reverse (I, II, A or B). The number is the position on a clockface of the 'N' in NEW SOUTH WALES or the 'F' in FIVE SHILLINGS, those numbers determined when the Holey Dollar is in the upright position.

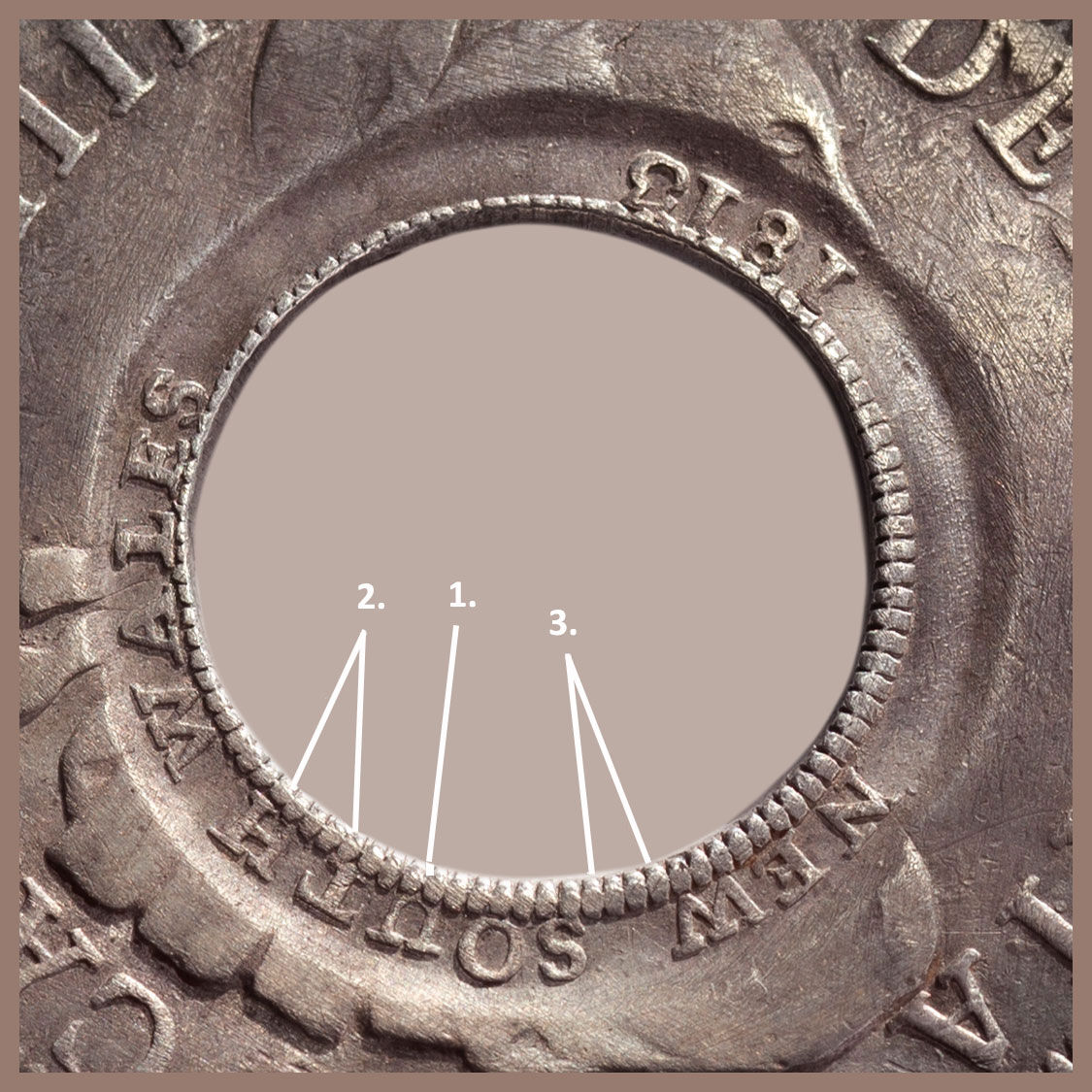

NEW SOUTH WALES 1813 - Die 'I'

Close-up of counterstamps on Holey Dollar shown here.

Counterstamp Die I/8

1. The 'U' of SOUTH is upright and its base sits on the denticles around the central hole

2. The crossbar of the 'T' in SOUTH is horizontal and level with the top of the 'H'

3. Two denticles separate the 'W' in NEW and the 'S' of SOUTH

Obverse of Holey Dollar struck from an 1808 Lima Mint Silver Dollar

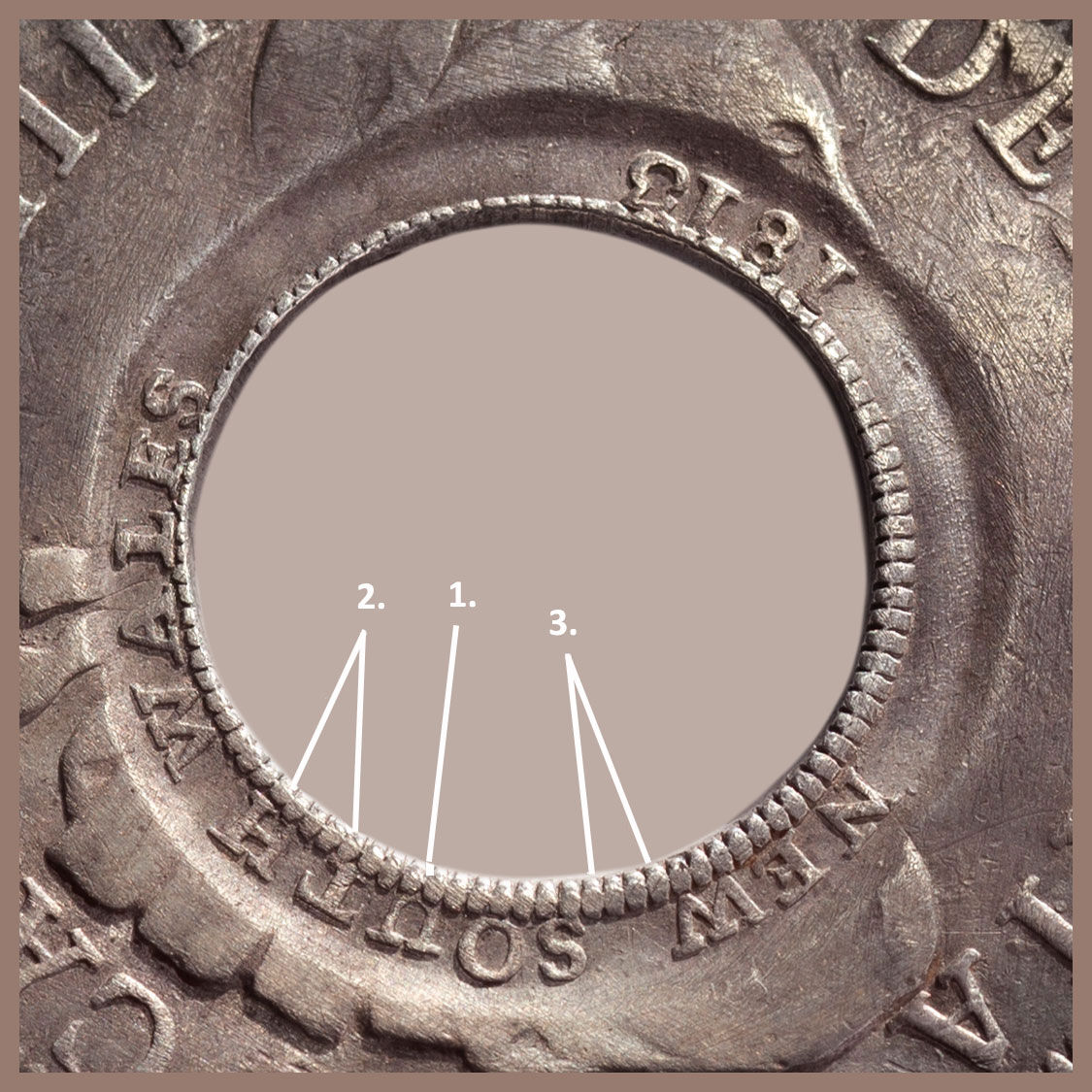

NEW SOUTH WALES 1813 - Die 'II'

Close-up of counterstamps on Holey Dollar shown here.

Counterstamp Die II/4

1. The 'U' of SOUTH is tilted to the left and its base is absorbed into the denticles around the central hole

2. The crossbar of the 'T' in SOUTH is horizontal and fractionally lower than the top of the ''H'

3. Four denticles separate the 'W' in NEW and the 'S' of SOUTH

Obverse of Holey Dollar struck from an 1801 Potosi Mint Silver Dollar

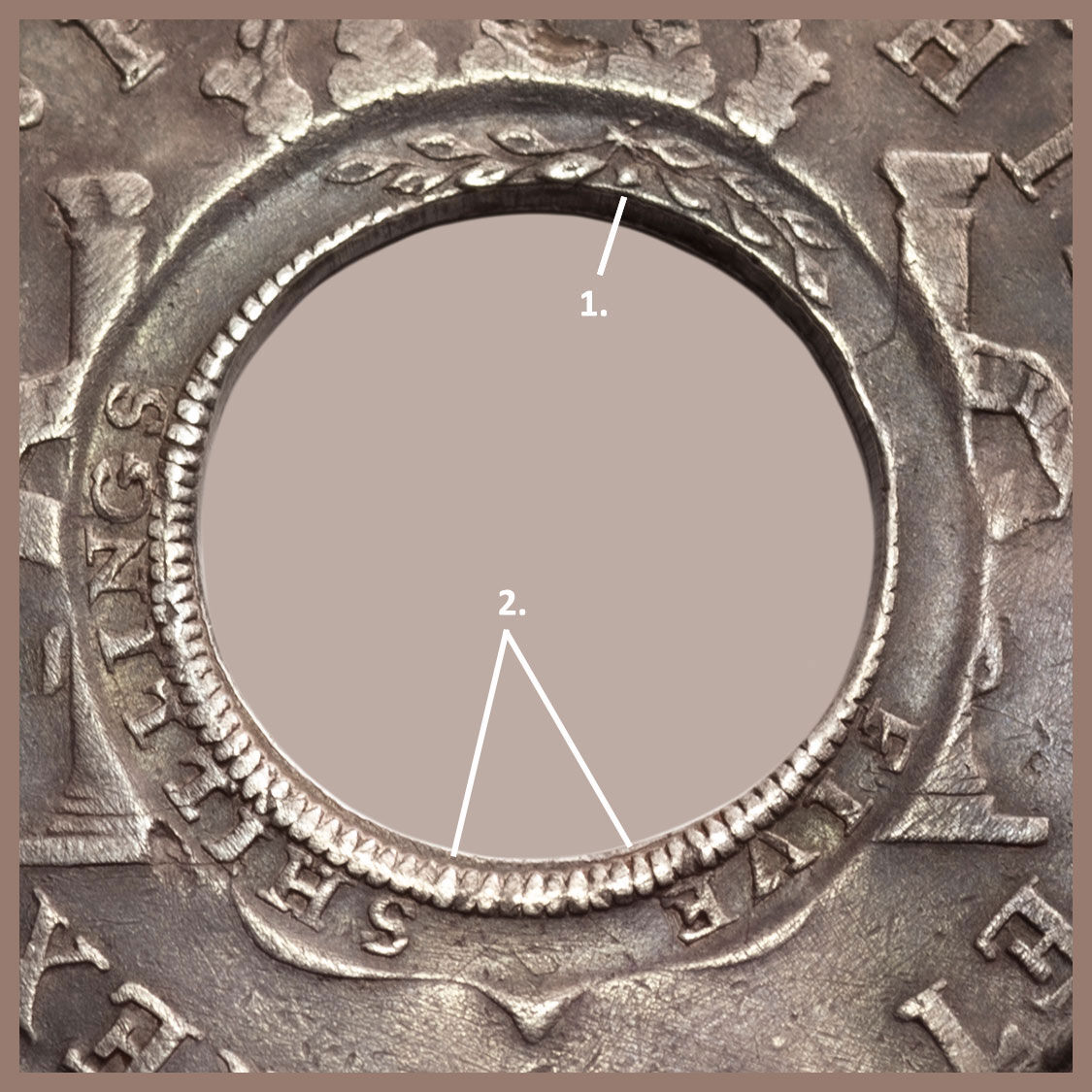

FIVE SHILLINGS - Die 'A'

Close-up of counterstamps on Holey Dollar shown here.

Counterstamp Die A/1

1. A fleur de lis is incorporated into the die between Five and Shillings (the only die where this occurs)

2. Each twig has six leaves, with a tiny 'H' at the junction

3. Twenty denticles are between the last letter in FIVE and the first letter of SHILLINGS

Reverse of Holey Dollar struck from an 1808 Lima Mint Silver Dollar

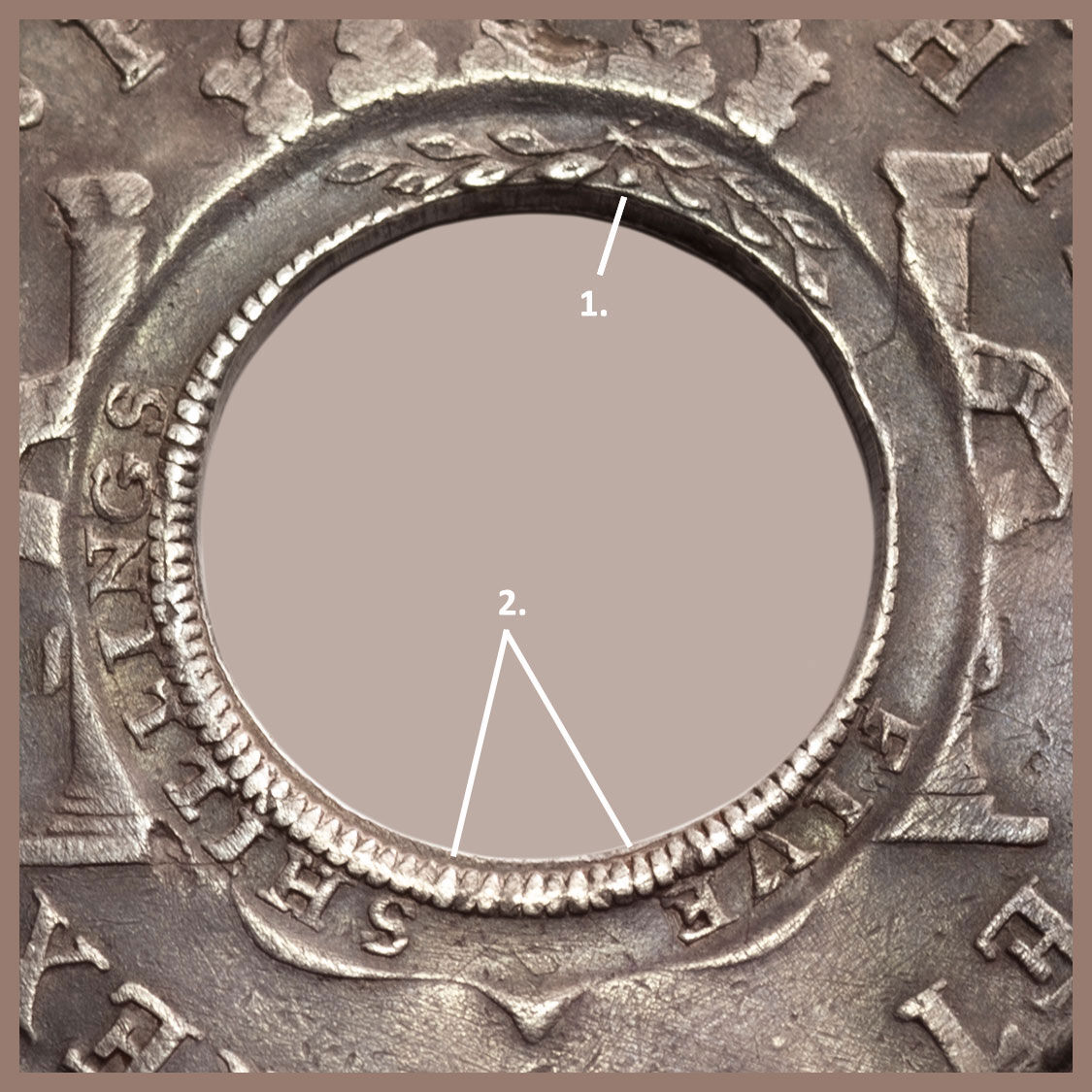

FIVE SHILLINGS - Die 'B'

Close-up of counterstamps on Holey Dollar shown here.

Counterstamp Die B/4

1. Each twig has six leaves and a tiny 'H' at the junction

2. Ten denticles are between the last letter in FIVE and the first in SHILLINGS

Reverse of Holey Dollar struck from an 1801 Potosi Mint Silver Dollar

An examination of the counterstamps

Four standard counterstamp dies have been identified. 'New South Wales' '1813' is deemed to be the obverse die and there are two variations, designated Die I and Die II. 'Five Shillings' is deemed the reverse die and there are also two design variations, designated Die A and Die B.

They appear in the following combinations.

• Die I with Die A (41 per cent)

• Die I with Die B (27 per cent)

• Die II with Die B (32 per cent)

It is noted that there are no Holey Dollars with the Die II and Die A combination.

Also noted these standard counterstamp die combinations appear in all but five Holey Dollars. Information is available on request on the non-standard dies used on the five known Holey Dollars (designated III, C and D).

The identification of the dies takes the following format:

Die / Number between 1 and 12 : Die / Number between 1 and 12

The first die cited is that which appears on the Holey Dollar obverse (I, II, A or B), the second die is that appearing on the Holey Dollar reverse (I, II, A or B). The number is the position on a clockface of the 'N' in NEW SOUTH WALES or the 'F' in FIVE SHILLINGS, those numbers determined when the Holey Dollar is in the upright position.

NEW SOUTH WALES 1813 - Die 'I'

Close-up of counterstamps on Holey Dollar shown here.

Counterstamp Die I/8

1. The 'U' of SOUTH is upright and its base sits on the denticles around the central hole

2. The crossbar of the 'T' in SOUTH is horizontal and level with the top of the 'H'

3. Two denticles separate the 'W' in NEW and the 'S' of SOUTH

Obverse of Holey Dollar struck from an 1808 Lima Mint Silver Dollar

NEW SOUTH WALES 1813 - Die 'II'

Close-up of counterstamps on Holey Dollar shown here.

Counterstamp Die II/4

1. The 'U' of SOUTH is tilted to the left and its base is absorbed into the denticles around the central hole

2. The crossbar of the 'T' in SOUTH is horizontal and fractionally lower than the top of the ''H'

3. Four denticles separate the 'W' in NEW and the 'S' of SOUTH

Obverse of Holey Dollar struck from an 1801 Potosi Mint Silver Dollar

FIVE SHILLINGS - Die 'A'

Close-up of counterstamps on Holey Dollar shown here.

Counterstamp Die A/1

1. A fleur de lis is incorporated into the die between Five and Shillings (the only die where this occurs)

2. Each twig has six leaves, with a tiny 'H' at the junction

3. Twenty denticles are between the last letter in FIVE and the first letter of SHILLINGS

Reverse of Holey Dollar struck from an 1808 Lima Mint Silver Dollar

FIVE SHILLINGS - Die 'B'

Close-up of counterstamps on Holey Dollar shown here.

Counterstamp Die B/4

1. Each twig has six leaves and a tiny 'H' at the junction

2. Ten denticles are between the last letter in FIVE and the first in SHILLINGS

Reverse of Holey Dollar struck from an 1801 Potosi Mint Silver Dollar

Why Collectors Acquire the Holey Dollar

In the realm of rare coins, Holey Dollars exist on a different plane. They transcend mere collectibles and have become coveted objects that represent the pinnacle of Australia's numismatic industry, our very first coin.

Owning a Holey Dollar isn't just about adding another coin to a collection.

It's about indulging in an experience, a fusion of history and prestige and we hope the information provided above, triggers your interest.

Remember, you are not just buying a coin, you own the experience. So enjoy it!

Photo Gallery

Images of Continental and Colonial Bust Spanish Silver Dollars

Continental Dollar Obverse

struck at the Madrid Mint

Continental Dollar Reverse

struck at the Madrid Mint

Colonial Bust Dollar Obverse

struck at the Mexico Mint

Colonial Bust Dollar Reverse

struck at the Mexico Mint

Images of six Holey Dollars graded Fair to Uncirculated (obverse only)

Quality

Fair to Good

Quality

Fine

Quality

Very Fine

Quality

Nearly Extremely Fine

Quality

Good Very Fine

Quality

Uncirculated

The History of the Holey Dollar

That Australia was settled in 1788, and the Holey Dollar and Dump not struck until 1813, raises the question about the medium of currency operating in the intervening years.

No consideration had been given to the monetary needs of the penal settlement of New South Wales. It was planned on the assumption that it would be self-supporting, with no apparent need for hard cash for either internal or external purposes.

Even if it had been theoretically planned for, it would have been physically impossible for the British Government to fund this new venture. Britain’s own currency was in a deplorable state and the Royal Mint’s priorities were clearly set at making improvements on the home front, not diverting hard cash off-shore.

Foreign coins arrived haphazardly in trade, and acquired local acceptability and brief legal recognition, but what was received quickly left the colony to pay for imports.

The essence of all business is a medium of exchange. Having very little hard cash, the inhabitants, from governor to free settlers and convicts, improvised by issuing hand-written promissory notes, in denominations as low as 3d, to settle their debts.

Commercial transactions were also facilitated through barter of goods and services. Philip Spalding, numismatist and author, presents an account of the style (and cunning) of barter in the colony circa 1800 in his literary works, ‘The World of the Holey Dollar’.

“One lover of the drama, not having rum or flour presented at the theatre door a neatly-dressed haunch of kangaroo, which was accepted. To the infinite disgust of the manager, it was discovered to be a haunch of a favourite greyhound, belonging to an officer, which the fellow had stolen, killed off and passed off as kangaroo meat at 9d per pound.”

Liquor was the prime commercial force and medium for barter in the colony and for almost forty years was part of the wages received by a considerable section of the population.

Governor Lachlan Macquarie’s communication to Viscount Castlereagh on the 30th April 1810 re-affirmed the financial plight of the colony. “In consequence of there being neither gold or silver coins of any denomination, nor any legal currency, as a substitute for specie in the colony, the people have been in some degree forced on the expedient of issuing and receiving notes of hand to supply the place of real money, and this petty banking has thrown open a door to frauds and impositions of a most grievous nature to the country at large.”

By 1812 the social fabric of Sydney as a community was emerging. It was no longer a redistribution point for convicts, with only the military as permanent residents.

Streets were being named. Macquarie, Phillip, Elizabeth, Castlereagh, Pitt and George Street. A post office was established and the common had been christened Hyde Park. Houses had to be aligned and numbered and heavy industry was being re-located out of the city centre to the suburbs.

Despite the social improvements, there was no bank and liquor remained the most commonly negotiated medium of currency exchange.

Rum, which cost 7/6 a gallon was being sold for up to £8 and its use as a negotiating medium was utilized by all sections of the community, including government. And the highest levels of Government at that. Even Lachlan Macquarie used rum to buy a house. The cost? 200 gallons.

He furthermore gave the Government contract to construct the Sydney Hospital in 1811 to Messrs. Riley and Blaxcell and paid for it by granting a three-year monopoly in the spirit trade and the right to import 45,000 gallons of rum.

By 1812, the penal colony of New South Wales had shaken off the shackles of being a receptacle for convicts. It was no longer a ‘jail’. And was emerging as a structured society and a commercial hub.

The stage was set for Governor Lachlan Macquarie to introduce Australia’s first currency.

Governor Lachlan Macquarie etched his name into numismatic history forever when in 1812 he imported 40,000 Spanish Silver Dollars to alleviate a currency crisis in the infant colony of New South Wales.

The British Government had no capacity to supply Governor Lachlan Macquarie with metal blanks to create Australia’s first coinage so, he improvised and ordered 40,000 Spanish Silver Dollars - foreign coinage - to use as his substitute for blanks.

Concluding that the shipment of 40,000 Spanish Silver Dollars would not suffice, and to hinder their export, Macquarie decided to cut a hole in the centre of each dollar, thereby creating two coins out of one, a ring dollar and a disc. It was an extension of a practice of ‘cutting’ coins into segments, widely used throughout the British colonies of the Caribbean and several African nation’s including Sierra Leone.

Macquarie needed a skilled coiner to carry out his coining project. William Henshall, acquired his skills as an engraver in Birmingham, where the major portion of his apprenticeship consisted of mastering the art of die sinking and die stamping for the shoe buckle and engraved button trades. He was apprehended in 1805 for forgery (forging Bank of England Dollars) and sentenced to the penal colony of New South Wales for seven years.

Enlisted by Lachlan Macquarie as the colony’s first mint master, Henshall commenced the coining process by cutting out a disc from each silver dollar using a hand-lever punch.

He then proceeded to re-stamp both sides of the holed dollar around the inner circular edge with the value of five shillings, the date 1813 and the issuing authority of New South Wales. Other design elements in this re-stamping process included a fleur de lis, a twig of two leaves and a tiny ‘H’ for Henshall.

The Holey Dollars were officially known as ring, pierced or colonial dollars and although ‘holey’ was undoubtedly applied to them from the outset, the actual term ‘holey’ dollar did not appear in print until the 1820s.

We refer to the coins today as the 1813 New South Wales Five Shillings (or Holey Dollar).

The silver disc that fell out of the hole wasn’t wasted. Henshall restamped the disc with a crown, the issuing authority of New South Wales and the lesser value of 15 pence and it became known as the Dump. The term ‘dump’ was applied officially right from the beginning; a name that continues to this day.

In creating two coins out of one, Macquarie effectively doubled the money supply. And increased their total worth by 25 per cent.

Anyone counterfeiting ring dollars or dumps were liable to a seven year prison term; the same penalty applied for melting down. Jewellers were said to be particularly suspect. To prevent export, masters of ships were required to enter into a bond of £200 not to carry the coin away.

Of the 40,000 silver dollars imported by Macquarie, records indicate that 39,910 of each coin were delivered to the Deputy Commissary General’s Office by January 1814 with several despatched back to Britain as specimens, the balance assumed spoiled during production.

The New South Wales colonial administration began recalling Holey Dollars and Dumps and replacing them with sterling coinage from 1822.

The Holey Dollar and Dumps remained as currency within the colony until 1829. The colony had by then reverted to a standard based on sterling and a general order was issued by Governor Darling to withdraw and demonetise the dollars and dumps.

The recalled specie were eventually shipped off to the Royal Mint London, melted down and sold off to the Bank of England for £5044.

It is estimated that 300 Holey Dollars exist today of which a third are held in public institutions with the balance owned by private collectors.

Highlights of Coinworks Inventory

© Copyright: Coinworks