The 1813 Dump, the nation's first coin and the partner to the 1813 Holey Dollar. Find out more about this classic Australian rarity.

In a letter to Lord Bathurst (London) in July 1822, Governor Lachlan Macquarie reflected on his impressions of the colony of New South Wales, when he arrived in 1810.

"I found the colony barely emerging from infantile imbecility and suffering from various privations and disabilities: the countryside impenetrable 40 miles from Sydney; agriculture in a yet languishing state; commerce in its early dawn; revenue unknown; the public buildings in a state of dilapidation and mouldering to decay: no public credit nor private confidence ... The credit of the colony was very low when I arrived on account of the base paper currency which was then the only circulating medium, the lowest and most profligate persons issuing their notes of hand in payment of goods purchased without having the means of redeeming them when due."

The story of Australian money in the first twenty five years is the introduction of forms of money and money-substitutes, conditioned by the absence of a local Treasury and by the emergence of a market economy.

The First Fleet, under the command of Captain Arthur Phillip, had set sail on 12 May 1787, with eleven vessels, 1482 persons, provisions and no currency, other than that which was personally held by its passengers..

The initial medium of exchange of the infant colony was the Government's Store Receipts. Issued for payment of produce, the receipts could be converted to bills on the His Majesty's Treasury, London.

Foreign coins arrive haphazardly in trade or in officers purses and convicts pockets, acquiring local acceptability and brief legal recognition. But they were inadequate to meet the needs of the colony.

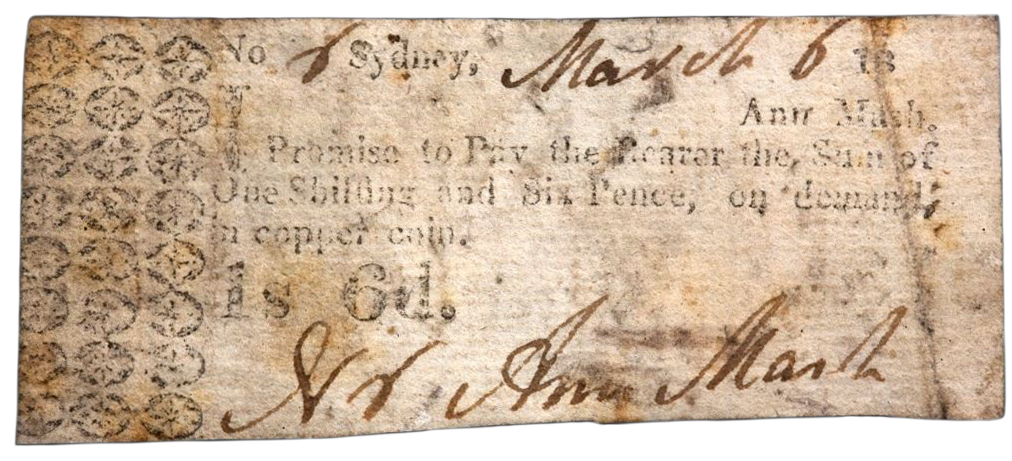

The liberal use of rum as a medium of barter flourished. And every merchant became a self appointed banker issuing promissory notes. Written notes, scraps of paper both literally and figuratively, were used indiscriminately by a broad cross section of the population to settle debts, including government, the judiciary, free settlers and convicts alike.

The promissory notes were only as good as the worth of the issuer. Forgeries were common. Many circulated for great lengths of time and often were never presented. This encouraged drawers to use ink that would fade.

In a way, the failure of Governors King (1800 to 1806) and Bligh (1806 - 1808) to stem promissory notes was evidence of the vitality with which private enterprise was growing in the colony.

In 1810, Macquarie, as the new Governor of the penal colony of New South Wales, put forward a plan for a bank as a Government institution. He also requested £5000 of copper currency, low denomination coinage, to curb the use of promissory notes. Both plans, the bank and the copper coin, were rejected.

By way of consolation, Macquarie was sent £10,000 of Spanish silver dollars (40,000 coins) with a request to take the necessary steps to prevent their export.

He secured the retention of the imported dollars by cutting out a circular disc from each coin. The holed dollar and the metal disc that fell out of the hole was over-stamped and transformed into a local, purely over valued coinage. The Holey Dollar and Dump.

A deterrent to their export was their reduced silver content. However to further prevent export, masters of ships were required to enter into a bond of £200 not to carry the coin away.

Anyone counterfeiting holey dollars or dumps were liable to a seven year prison term; the same penalty applied for melting down. Jewellers were said to be particularly suspect.

Macquarie had high hopes for the Holey Dollar and Dump, and in particular the Dump.

He stated that the Dump would fill the role of small change and would remove much of the need for promissory notes of low denominations.

So convinced was he about the efficacy of the low denomination Dump that his proclamation dated 30 September 1813, giving the Holey Dollar and Dump legal tender status, also banned the issue of promissory notes of less than two and sixpence (or the equivalent of two Dumps).

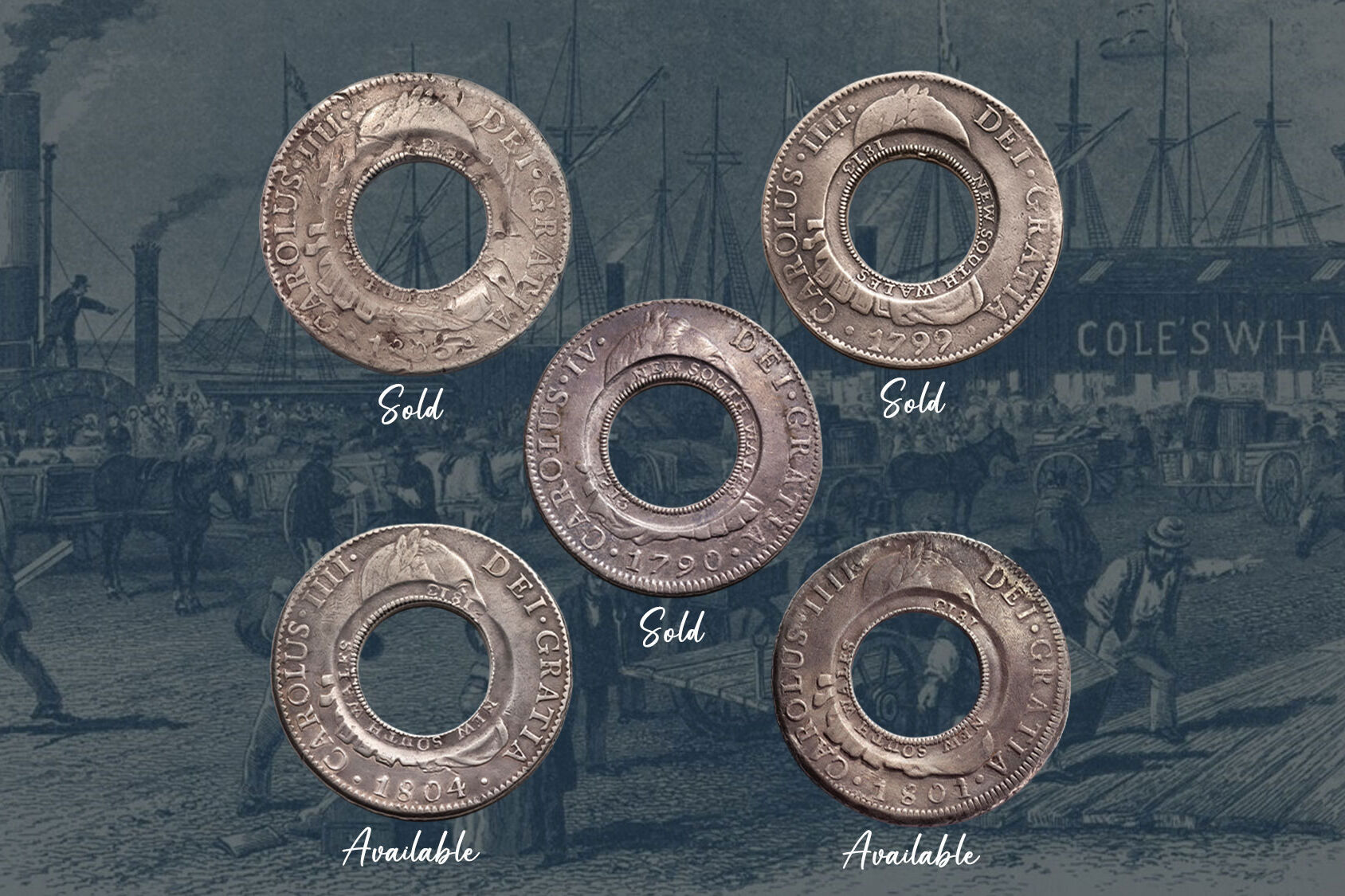

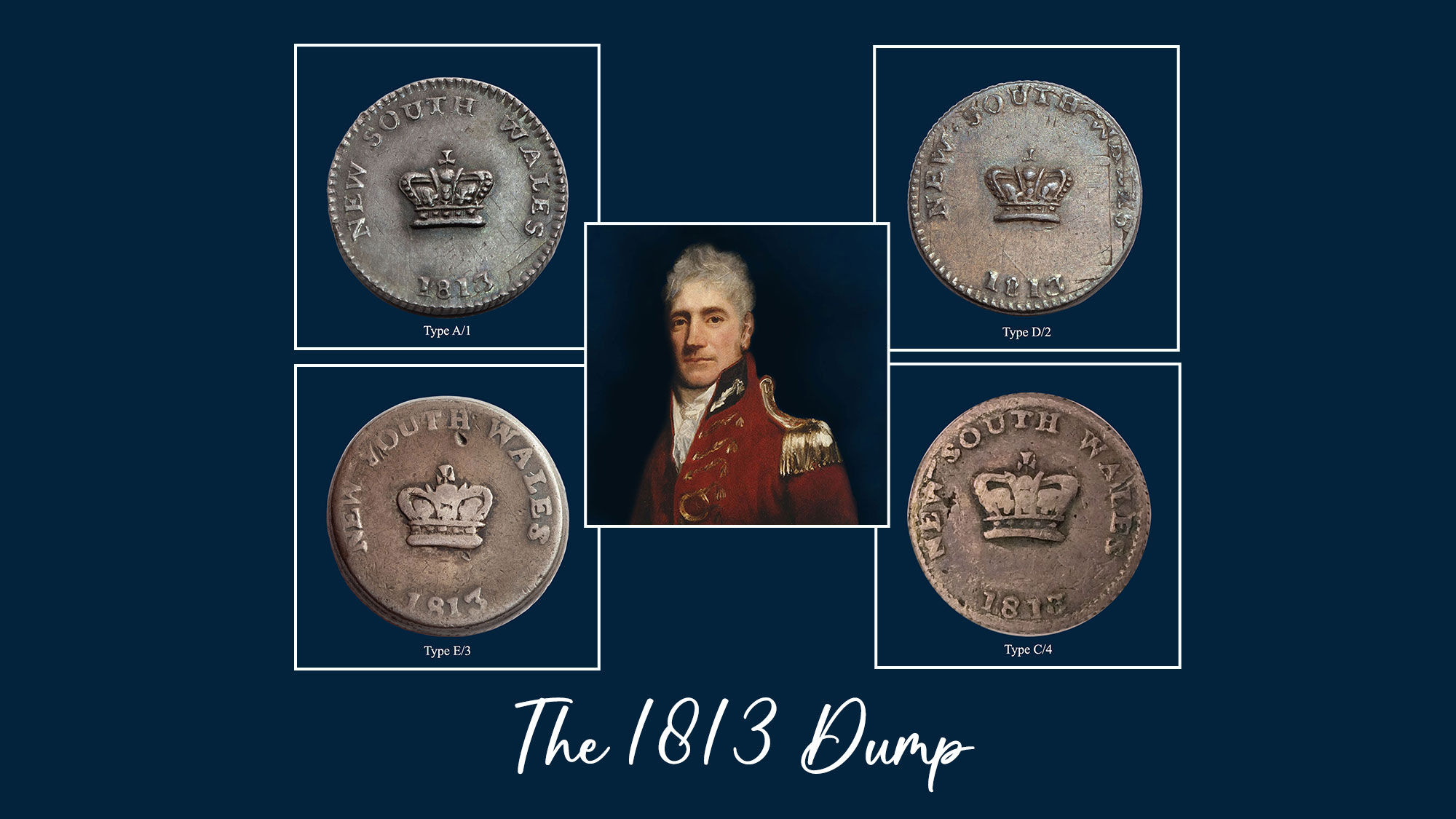

1813 Dump

obverse die A

1813 Dump

obverse die D

1813 Dump

obverse die E

1813 Dump

obverse die C

The industry acknowledges that there are about one thousand surviving examples of the 1813 Dump, with eight hundred available to collectors, the balance held in museums and public institutions.

Within that collector pool, the Dump appears in four distinctly different die combinations or styles. The four combinations have been classified by respected collector and author Bill Mira as the type A/1, D/2, E/3 and C/4, the letter referring to the obverse die, the numeral representing the reverse die.

No examples have been identified that differ from the four styles.

On the obverse, the different styles are reflected in the shape of the cross on the crown, the position of this cross in relation to the letters in the legend above it. And in the shapes and positioning of the row of five jewels in the band of the crown.

On the reverse, differences are found in the distances between the words 'FIFTEEN' and 'PENCE' and in the position of the 'T' in 'FIFTEEN' in relation to the 'N' in 'PENCE'.

Historians suggest that the D/2 dies were likely the first die combination used, for the coins exhibit weaknesses in the edges and the legend, suggesting that the die was too large for the silver disc.

Of the 800 surviving Dumps in collector's hands, 20 per cent were struck using the D/2 dies.

The A/1 die combination appears in 75 per cent of surviving Dumps, producing a coin that was well centred and framed by edge denticles, eliminating a lot of the design deficiencies of the D/2 combination.

The E/3 and C/4 dies produced coins that were very crude and esoteric and tend to be enjoyed by collectors seeking to acquire one of each style. There is a suggestion that they may have been test pieces presented to Governor Macquarie before production began. Or the work of another engraver that was discarded due to the poor result.

Many of the C/4 Dumps, in particular, have surface cracks and splits supporting the theory that they were produced to establish the correct striking pressure and planchet temperatures. That they may have been contemporary forgeries struck in silver, has also been muted.

Irrespective, the E/3 and C/4 Dumps are extremely rare and an essential part of the 'Dump' story.

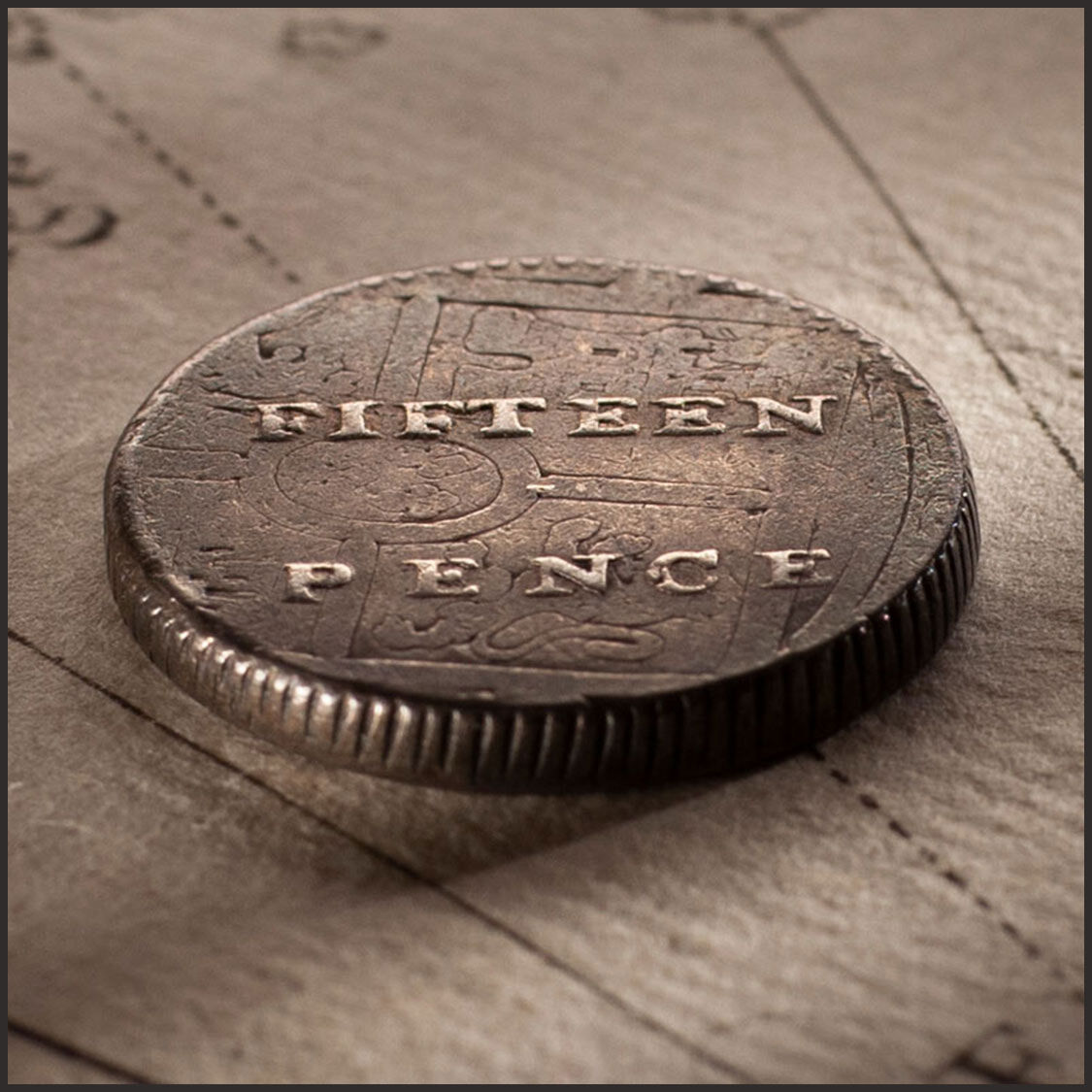

1813 Dump

reverse die 1

1813 Dump

reverse die 2

1813 Dump

reverse die 3

1813 Dump

reverse die 4

No one really knows how the Dump (and the Holey Dollar) were actually manufactured. The documentation as to the method has never been found. It is safe to assume that whatever machinery was employed, it was hand operated as the first steam engine did not become operational in the colony until 1815.

Likely production options were the screw press, drop hammer or hand-held punch with the drop hammer method onto a pre-heated plug generally regarded as the most likely.

There is no doubt that heat was involved in the creation of the Dump.

When the disc fell out of the centre of the Spanish Dollar, it still bore the original dollar design of a four quadrant shield, housing a lion in two diagonally opposite quadrants and a castle in the other two.

Early suggestions that the circular disc was cleaned of the dollar design has been ruled out as the combined weight of the Dump and Holey Dollar is comparable to an intact Spanish Silver Dollar.

Historians now contend that high temperatures were used to obliterate the original Spanish Dollar design from most examples. Dumps that depict their origins, by retaining their original dollar design elements, are highly prized.

The high temperatures also caused an expansion of the metal disc that fell out of the dollar. The very reason why the Dump is always larger than the hole in the Holey Dollar.

The grooved edge milling found on the dumps indicates that a 'fiddle method' was the final step in the production process whereby a roll of Dumps was rotated under pressure against a grooved cylinder.

The edge milling (as well as the denticles on the rim) were a deterrent against 'clipping'; a practice whereby the unscrupulous would shave off slivers of silver from the edges. If undetected, the Dump could still be traded at its nominal value and a small profit made on the side by selling off the silver as bullion.

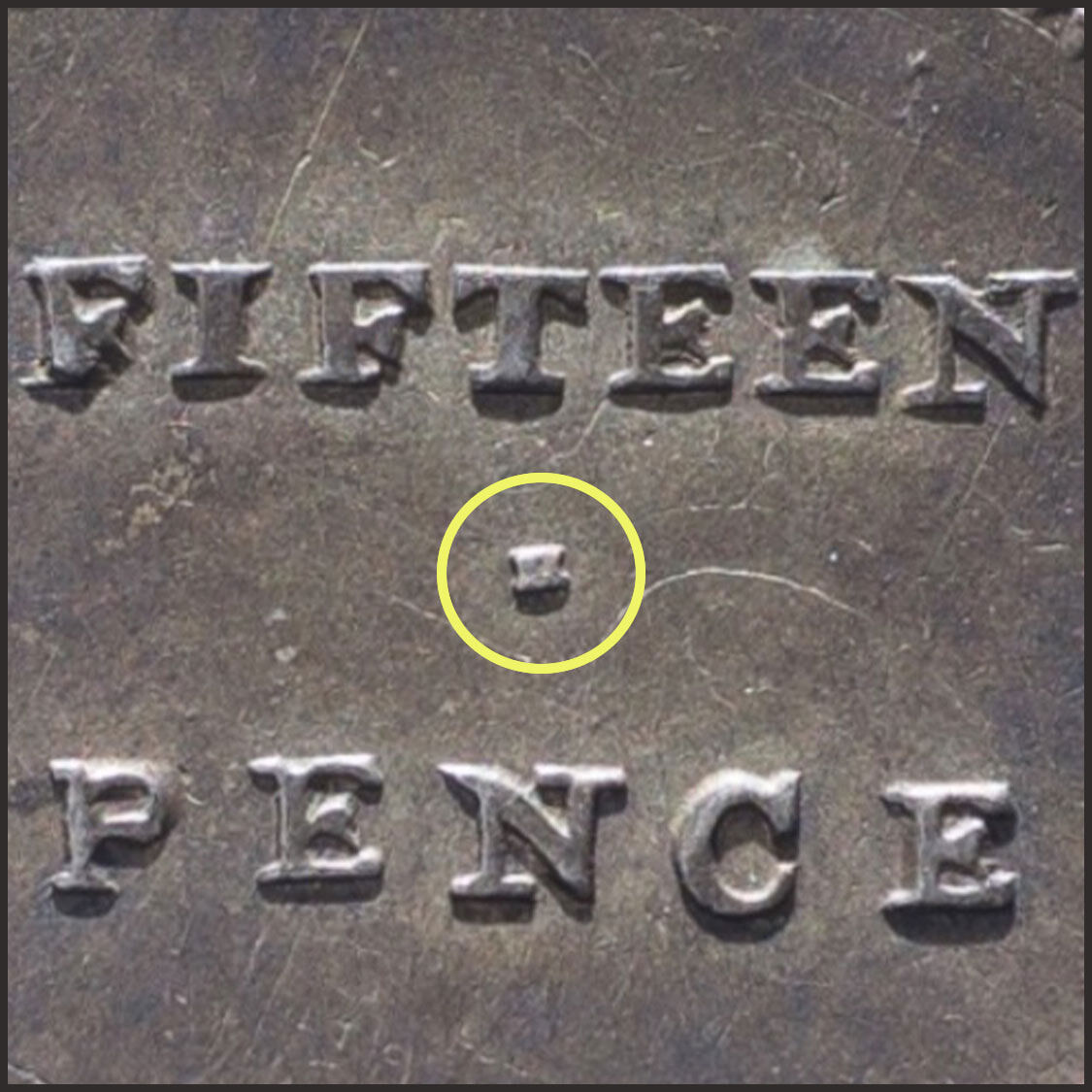

While the method of manufacture of the nation's first coins is unknown, history records that convicted forger and emancipist, William Henshall, was hired to create the nation's first currency. Effectively our first Mint Master.

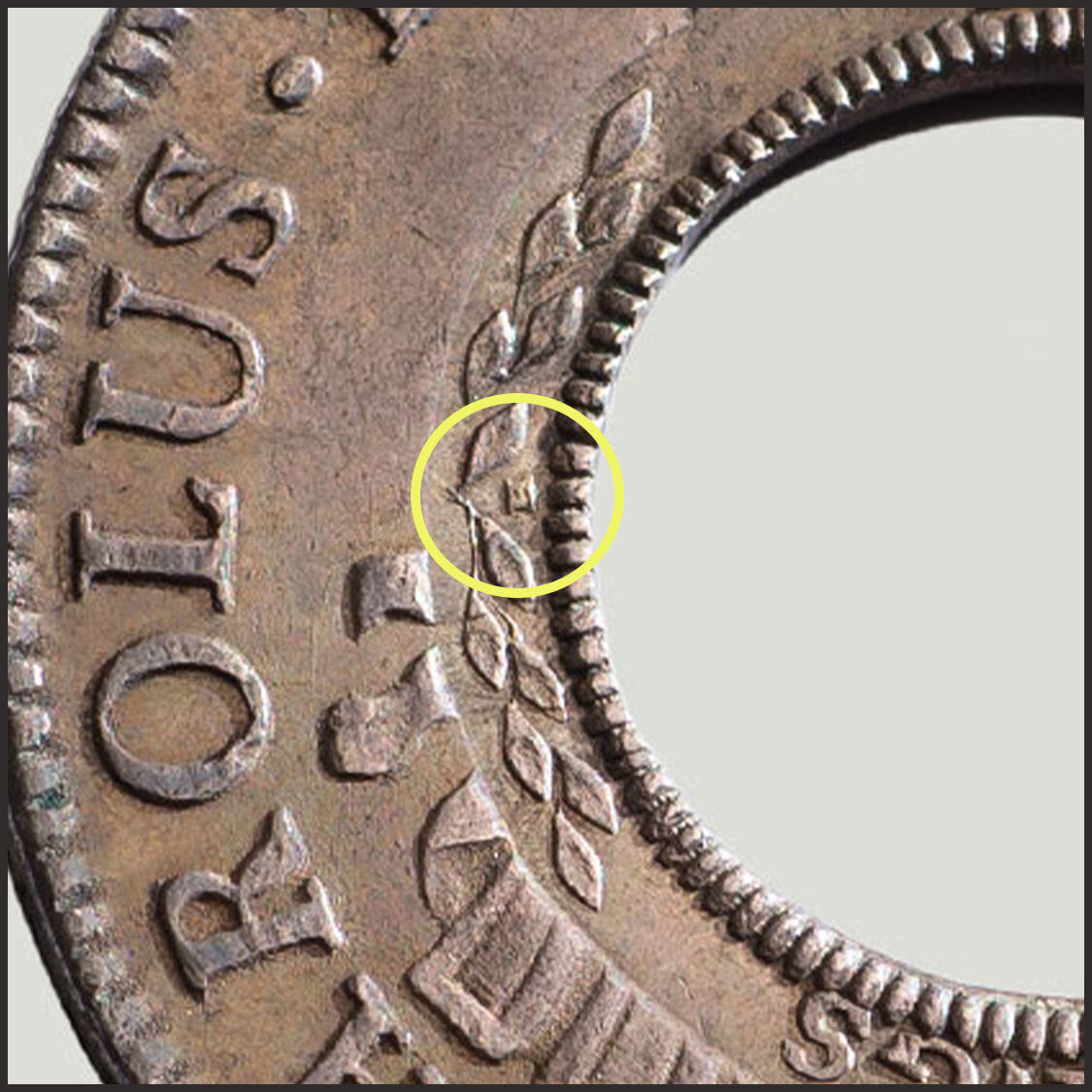

Henshall declared his involvement in the creation of the Dump - and the Holey Dollar - by inserting his initial, an 'H' for Henshall, on some - but not all - of the reverse dies of the Dump. And some - but not all - of the Holey Dollar counter stamp dies. Its presence is also highly prized.

The Spanish Silver Dollar showing the design of the shield and the quadrants.

1813 Dump showing extensive elements of the original dollar design.

Circled, Henshall's claim to fame on the Dump reverse between 'FIFTEEN' and 'PENCE'.

Circled, the 'H' between the two twigs of leaves in the Holey Dollar counter-stamps .

Why Collectors acquire the 1813 Dump

The Holey Dollar and Dump represent the pinnacle of Australia's numismatic industry, our very first coins.

Buying a Holey Dollar or a Dump is like buying a BMW motor vehicle and choosing between the top of the range BMW 7 series or the slightly smaller BMW 5 series.

Both dynamic vehicles, and a joy to own, the latter available in a price range that caters to more buyers.

And so it is with the Dump.

The coin is a rarity in its own right and is very much sought after, catering to more collectors.

Final points to consider when acquiring a Dump

The buyer that pursues a top quality 1813 Dump will find the task extremely challenging. It can be years before a premium quality example comes onto the market and decades before the very best becomes available. And that statement is said in the knowledge that there are perhaps 800 Dumps, across all quality levels, available to private collectors.

The Dump with a value of fifteen pence circulated widely in the colony, the extreme wear on most Dumps evidence that they saw considerable use. The Holey Dollar being a higher valued piece, at five shillings, had a narrower band of circulation and was held by the colony's first bank, the Bank of New South Wales as a reserve. Historians also suggest that, as they were legal tender and could be used to buy Bills on London, they tended to be hoarded by its citizens.

So, while the Dump may seem the diminutive partner of the Holey Dollar, the reality is top quality Dumps have authority. They are extremely rare, in fact far rarer than their holed counterpart in the same quality level.

As such, Dumps are highly valued.

You can acquire a well used 1813 Dump for $5,000 to $10,000. Of course you won’t see much of the design, it will almost be obliterated. Moving up the quality scale you will find a 'Fine' to 'good Fine' Dump for $15,000 to $20,000. The design will be evident, but flattened, and the coin will more than likely be knocked around.

Buyers that are looking for a higher quality example might stretch their budget with the expectations of a $25,000 to $35,000 outlay and so walk away with an 'About Very Fine' to 'Very Fine' Dump.

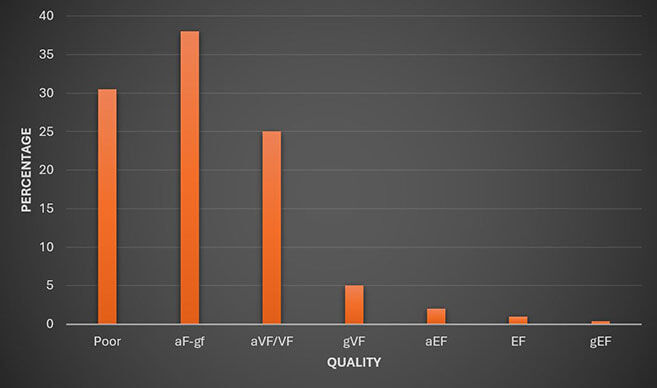

What is obvious from the chart below is that 'Good Very Fine' is the point at which extreme rarity kicks in for the 1813 Dump. The buyer that is looking for a high quality Good Very Fine Dump will have to extend their budget to $50,000 with perhaps an upper ceiling of $65,000. Acquiring a Dump at this quality level is not only about the dollars involved. Its about exercising a lot of patience for you can realistically be looking at a one-year time frame, perhaps even longer.

It is at the quality level of About Extremely Fine, and higher, that the task of finding a Dump becomes tough and challenging, invariably involving several years. And a price range upwards of $75,000. The chart below clearly shows that at a quality level of About Extremely Fine to Extremely Fine you are in 'rarefied air' with very few examples becoming available. And that the quality ranges of Good Extremely Fine and up to Uncirculated are an absolute 'killer' for acquisition.

Quality: Fine

Quality: Very Fine

Quality: Good Very Fine

Quality: Good Extremely Fine

Quality: Fine

Quality: Very Fine

Quality: Good Very Fine

Quality: Good Extremely Fine

Design characteristics of a Dump struck with the A/1 dies

Obverse die A:

An imaginary line drawn along the base of the Crown will cut the 'N' of 'NEW' and passes above or through the top of the 'S' of 'WALES'.

The cross is symmetrical and points between the 'T' and the 'H' of 'SOUTH'.

The '3' in 1813 tilts to the left

Five jewels are detailed in the band, the left-most pearl touching the base of the band. The right-most jewel touching the top of the band.

Some pieces also show a dot above the '3' in 1813. This is almost certainly due to a pit in the die, which filled up during production.

Reverse die 1:

The upright stroke of 'F' in 'FIFTEEN' is to the left of the upright stroke of 'P' in 'PENCE.

The vertical stroke of 'T' is over the centre of the 'N'.

'FIFTEEN' and 'PENCE' are 4.5mm apart.

Design characteristics of a Dump struck with the D/2 dies

Obverse die D:

An imaginary line drawn along the base of the Crown will pass under the 'N' of 'NEW' and through the 'S' of 'WALES'.

There is a stop in the legend after the word 'NEW' and after the word 'SOUTH'.

The cross is symmetrical and points between the 'U' and 'T' of 'SOUTH'.

The '3' in 1813 tilts to the left

The five jewels are equal in size and are close to the top of the band, often touching it in worn examples.

Reverse die 2:

The upright stroke of 'F' in 'FIFTEEN' is left of the upright stroke of 'P' in 'PENCE.

The vertical stroke of 'T' is well left of the centre of the 'N'.

'FIFTEEN' and 'PENCE' are 5mm apart.

Design characteristics of a Dump struck with the E/3 dies

Obverse die E:

An imaginary line drawn along the base of the Crown will cut through 'N' of 'NEW' and passes under the 'S' of 'WALES'.

The cross is asymmetrical and tilts to the left, pointing between the 'T' and the 'H' of 'SOUTH'.

The '3' in 1813 tilts to the left.

The five jewels vary in size, with two of them smaller than the others. And their position in the band also varies. The left-most pearl touches the top of the band with the other four central.

Reverse die 3:

The upright stroke of 'F' in 'FIFTEEN' is to the right of the upright stroke of 'P' in 'PENCE.

The vertical stroke of 'T' is over the left hand vertical stroke of the 'N'.

'FIFTEEN' and 'PENCE' are 3.5mm apart.

Design characteristics of a Dump struck with the C/4 dies

Obverse die C:

An imaginary line drawn along the base of the Crown passes above the 'N' of 'NEW' and above the top of the 'S' of 'WALES'.

The cross points between the 'T' and the 'H' of 'SOUTH'.

The '3' in 1813 is upright.

The five jewels are diamond-shaped and are central in the band.

Reverse die 4:

The upright stroke of 'F' in 'FIFTEEN' is to the right of the upright stroke of 'P' in 'PENCE.

The vertical stroke of 'T' is well left of the centre of the 'N'.

'FIFTEEN' and 'PENCE' are 4mm apart.

There is a round punch mark in the centre of the reverse.

Coinworks recommends

© Copyright: Coinworks