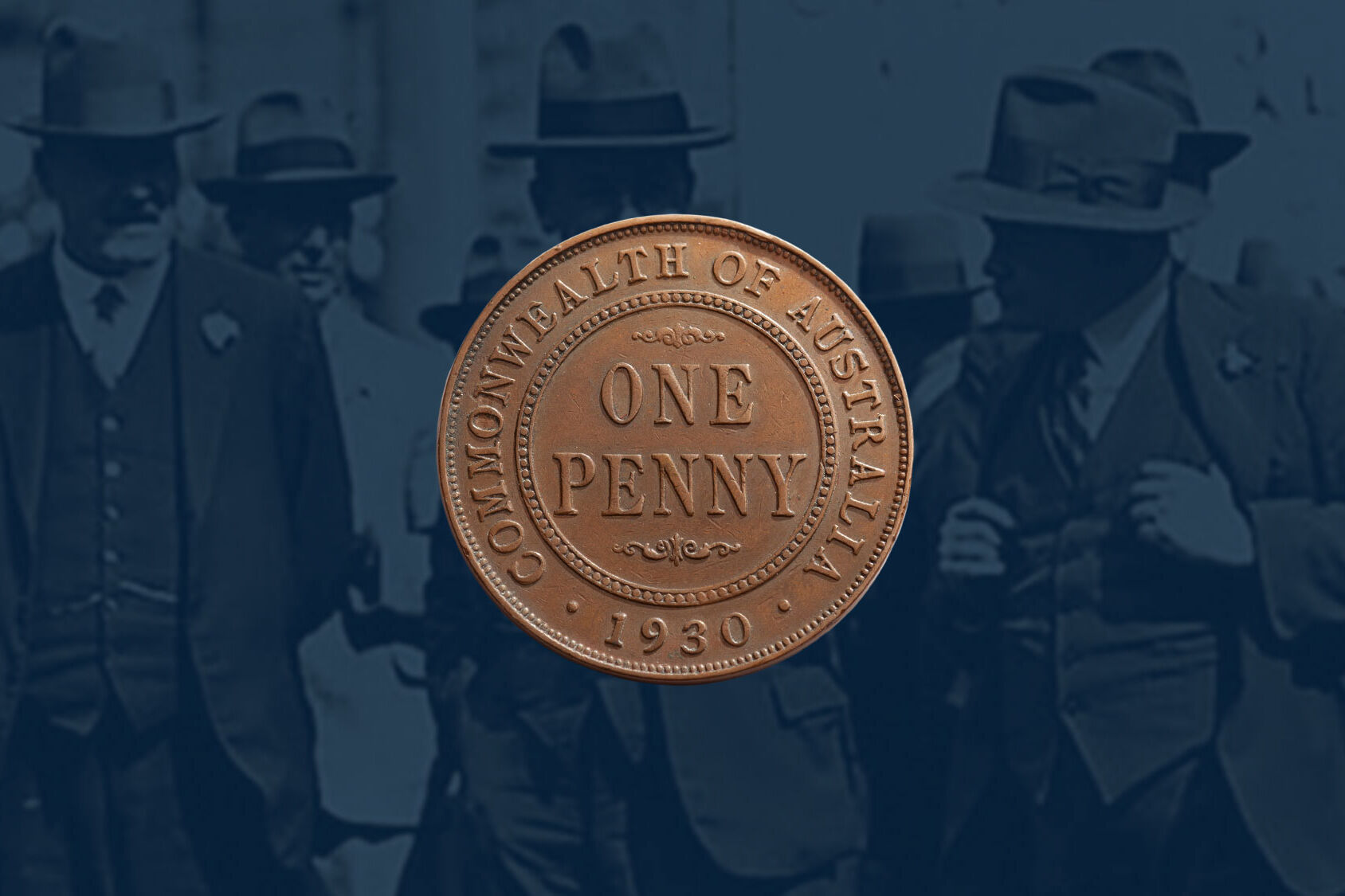

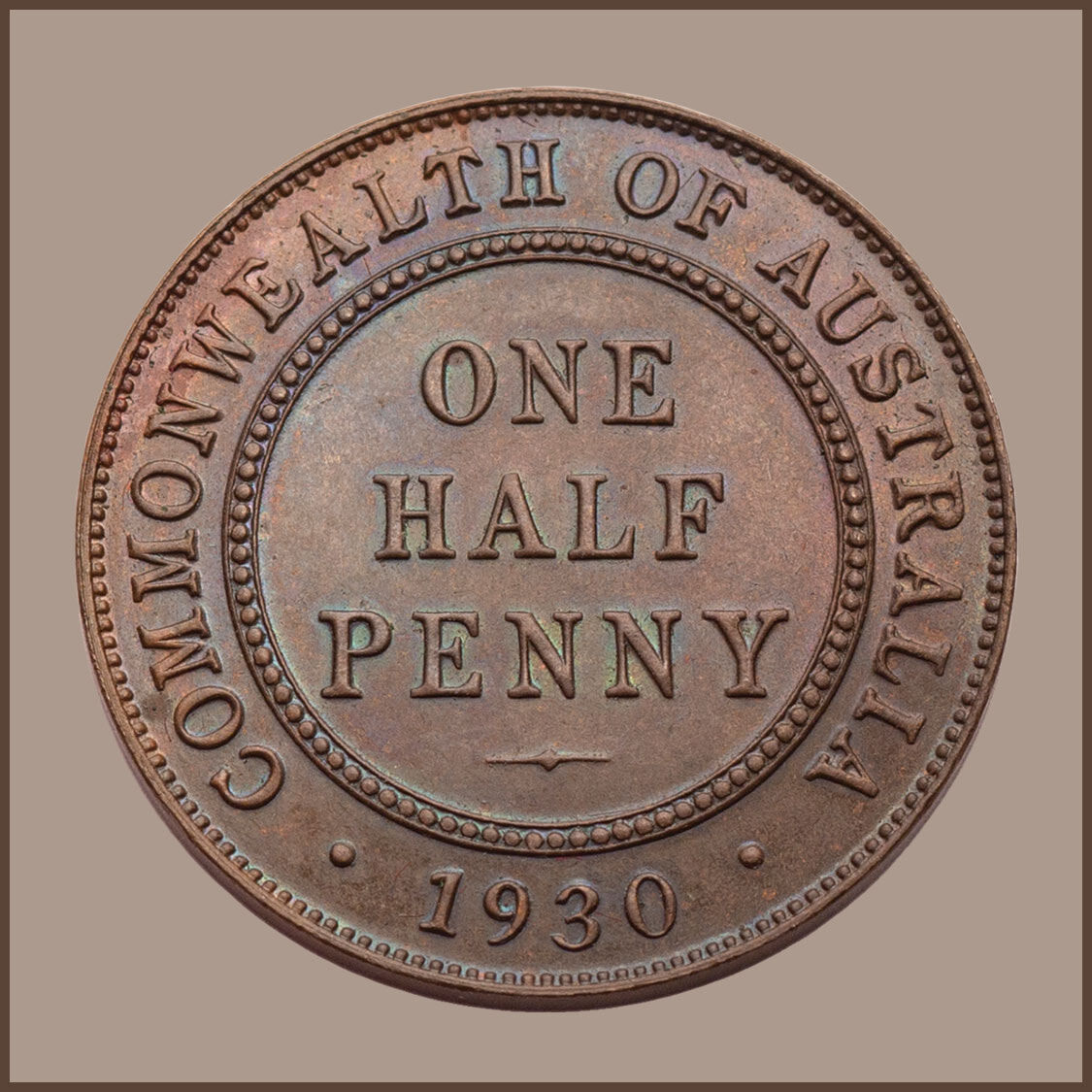

The Proof 1930 Halfpenny struck as a Coin of Record at the Melbourne Mint and one of three known

Australians just love their coppers. And within the penny and halfpenny series, collector preference is for those coins that were struck in limited mintages, that are especially rare in today's market.

Pennies such as the illustrious 1930 Penny and the revered 1925 Penny, rare dates that were struck in mintages of 1500 and 117,000 respectively.

And the 1923 Halfpenny, also a rare date, the mintage believed to be 15,000.

The Penny and the halfpenny have a connection when it comes to values.

When the penny has a rare date status, it influences that value of its proof counterpart. But it also influences the value of its proof halfpenny counterpart.

The very reason why the Proof 1930 Penny and the Proof 1930 Halfpenny are seen as numismatic greats and are highly valued. So too, the Proof 1925 Penny and the Proof 1925 Halfpenny.

The Proof 1930 Halfpenny

The Proof 1930 Halfpenny

Proof coins are prestigious. And proof coins are extremely rare. And if they have been carefully preserved, proof coins are spectacular to look at with pristine edge denticles, a highly detailed design set against a backdrop of superb, smooth and highly reflective fields.

Under careful examination, proof coins will also show striations in the fields, a by-product of the intensive die preparation involved in proof coining. And the edges will be highly polished.

Place a proof coin next to an Uncirculated coin and the differences are clear, even to the naked eye.

Proofs command respect and they command admiration.

Ask collectors why they pursue proof coins over circulating currency and the prestige of owning a proof coin is most likely at the top of their list. It's the euphoria that comes with owning something that looks spectacular and that very few other people can ever possess.

In some respect, proof coin collectors are playing it smart because the inherent rarity of proof coinage provides a level of assurance that the market will never be inundated with examples, protecting their investment.

The Proof 1930 Halfpenny struck as a Coin of Record at the Melbourne Mint and one of three known

Price $75,000

Noble Numismatics Auction August 1999, lot 3181 • Madrid Collection of Australian Rare Coins (see below).

FDC with iridescent mirror surfaces that reflect brilliant purple and emerald-green flashes, highlighting the date 1930 and highlighting the legend on both obverse and reverse. The inner beading is pristine. The edge denticles immaculate. A stunning coin!

The Madrid Collection of Australian Rare Coins was a multi-million dollar collection that contained a wealth of show-stoppers including the world famous Madrid Holey Dollar, long regarded as Australia’s most desirable example of the nation’s first coin. And the Proof 1930 Penny, the Sterling Silver Kookaburra Penny, the unique 1870 Proof Sovereign, the unique 1901 Perth Mint Proof Sovereign and Proof Half Sovereign pair. And of course, this Proof 1930 Halfpenny.

The Proof 1930 Halfpenny, a Coin of Record struck at the Melbourne Mint.

Australian Pre-decimal Coins that were struck to a proof or specimen finish - and not destined for collectors - are technically referred to as Coins of Record.

The term, Coin of Record, is to a large extent self-explanatory. It is a coin that has been minted to put on record a date. Or to record a design.

What is not self-explanatory is that Coins of Record were created as presentation pieces produced to a proof or specimen finish. And were struck in the most minute numbers satisfying the requirements of the mint rather than the wants of collectors. Forget the notion of striking ten thousand proofs as collectors are accustomed to today. Let's talk about striking a total of ten coins ... or maybe less!

For today’s collectors the Coins of Record offer a wonderful link to the past and are extremely rare, two reasons that make them so popular.

There was no commercial angle in the production of Coins of Record. The mints were not out to make money from the exercise. Quite the reverse, striking a proof coin in our pre-decimal era was a very labour intensive (and hence costly) exercise that would have dented the mints annual budget quite considerably. The prime reason why so few coins were struck.

In the striking of a proof coin, the mint’s intention was to create a single masterpiece, coining perfection. Perfection in the dies. Wire brushed so that they are razor sharp. Perfection in the design, highly detailed, expertly crafted. Perfection in the fields, achieved by hand selecting unblemished blanks, polished to create a mirror shine. Perfection in the edges to encase the design … exactly what a ‘picture frame does to a canvass’.

A proof is an artistic interpretation of a coin that was intended for circulation. A proof coin is meant to be impactful, have the ‘wow’ factor and exhibit qualities that are clearly visible to the naked eye. A proof coin was never intended to be used in every-day use, tucked away in a purse. Or popped into a pocket.

So, what happened to these Coins of Record? Where did they go? And if they were struck by the mints for their own use, how did they get into collector's hands?

In the main, Coins of Record ended up in the mint’s own archives, preserving its history for future generations. Any coins that were surplus to requirements may also have been sent to a museum or public institution.

Coins of Record were also put on display at public Exhibitions. The two known examples of the Proof 1866 Sovereign and Proof 1866 Half Sovereign were especially struck to exhibit as ‘products of New South Wales’ as part of the Colonial Mints display at the International Colonial Exhibition of 1866 and the International Exposition in Paris, 1867. They were discovered in London in the early 1970s.

It is noted that many of the overseas mints have over time sold off Coins of Record that they considered excess to their requirements allowing them to come into collector's hands. The Royal Mint South Africa sold off several Australian gold proofs in the 1990s

Highlights of our Inventory

© Copyright: Coinworks