One of the greatest pieces of Australiana our nation has to offer.

If perfection is to be had in a Holey Dollar then this coin is it.

The conundrum of this Holey Dollar is how it became to be presented in such a miraculous state.

It raises more questions than we can ever possibly answer and only adds to the intrigue and the mystery of this superb colonial gem.

The Holey Dollar began its life as a Spanish Silver Dollar. In the case of this Holey Dollar it began its life as a Spanish Silver Dollar that was minted at the Spanish colonial mint of Mexico, in 1805.

The coin was one of 40,000 Spanish Silver Dollars acquired by Governor Lachlan Macquarie in 1812, and that were destined to be converted into Holey Dollars and Dumps.

Given that the Spanish Silver Dollar was the most widely used, and accepted, coin in the world we ask the question.

How did an 1805 Spanish Silver Dollar retain its pristine state during the seven years up until its arrival in the colony of NSW?

Mint Master, William Henshall used a punch to cut out a disc from an 1805 Spanish Silver Dollar as the first step in creating this coin.

It was one of 40,000 Spanish Silver Dollars imported by Macquarie, but with one defining characteristic. By some fluke, the coin had never been used.

Henshall then placed the holed coin between two dies.

One die contained the elements ‘New South Wales’ and ‘1813’. The other die contained the denomination of ‘Five Shillings’, a fleur de lis, a double twig of leaves, and an ‘H’ for Henshall.

These elements are known as the counter stamps.

Using the gravitational force of a simple drop hammer system, the design elements of the dies were stamped onto both sides of the holed silver dollar around the inner circular edge of the hole.

And it is at this point – and this point only – that the ‘holed’ silver dollar became the 1813 New South Wales Five Shillings (or Holey Dollar).

An examination of the counter stamps reveals that this coin was never used even after it was transformed into a Holey Dollar.

The inner denticles, the lettering ‘Five Shillings’ and ‘New South Wales', date ‘1813’, the fleur de lis, double twig of leaves and tiny ‘H’ are as struck and fully detailed.

We know the process of striking the Holey Dollars was haphazard but was there a controlled hand in the minting of this coin? Was it especially selected?

The circular hole cut out by Henshall is beautifully centred. The edges of the coin are undamaged, the denticles as struck.

How soon into its life did this Holey Dollar become a collectable?

The coin was identified as belonging to Howard Gibbs, an active American collector in the 1920s. The same collector owned the world renowned Madrid Holey Dollar.

It is a statement of fact that the majority of high calibre Holey Dollars were originally held by collectors residing overseas, the United Kingdom and America in particular.

It is noted that Britain and America already had a sophisticated collector market in the nineteenth century that saw top rarities move between the two continents.

Was this Holey Dollar taken back to England early on in its life by free settlers returning home?

There is no doubt that the gentry would have had the financial capacity to hold their five shillings as a collectable. And would seek out a prime example to hold as part of their personal collection.

We have no answers to these questions.

All that we can say is that this is an exceptional Holey Dollar, and an heirloom without parallel.

A Holey Dollar that stands up to scrutiny. The facts.

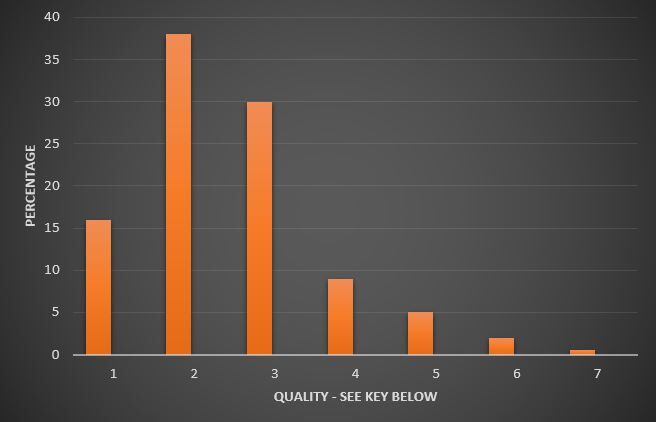

- Fair – Good. Heavily circulated, and akin to a washer.

- About Fine – Good Fine. Well circulated, knocked around and design details partially worn away.

- About Very Fine to Very Fine. Circulated with some elements of the design worn down.

- Good Very Fine. Circulated with design details slightly worn.

- About Extremely Fine – Extremely Fine. Slight wear. Design details intact.

- Good Extremely Fine. Well preserved and the slightest hint of wear.

- Uncirculated. The coin has never been used.

Unlike today’s obsessive collectors Governor Macquarie wasn’t fussy about the quality of the Spanish Silver Dollars he imported. He was a pragmatist, determined to supplement the colony’s dwindling currency supply with coinage. The majority of Silver Dollars that he acquired were well worn reflecting the Dollars extensive use as an international trading coin.

Our chart on the right details the quality of the 200 surviving Holey Dollars held by collectors. And re-affirms the exceptional quality characteristics of this coin.

What is obvious from this chart is that 93 per cent of Holey Dollars show visible signs of wear; wear that is clear to the naked eye.

Only 7 per cent of surviving Holey Dollars show minimal wear with only one example, this Holey Dollar, listed as Uncirculated.

Presentation.

Award winning craftsman Anton Gerner was commissioned by Coinworks to produce a presentation case for this Holey Dollar.

The case is hand-made and features an intricate inlay of Australian Birdseye Huon Pine, contrasting with Australian Blackwood. The interior is leather-lined.

Anton and his team of craftsman are committed to producing one-off designs made from materials of the finest quality using traditional construction and finishing techniques.

His reputation for excellence is based on 27 years of uncompromising attention to design and detail, the very reason why he was chosen to create a Presentation Box for Australia’s Number One Banknote, the Collins Allen Ten Shillings M0000001.

And again with the creation of presentation packaging for Australia’s ‘Number One’ Holey Dollar.

1788 – 1813. From penal colony to commercial hub. A nation emerges.

That Australia was settled in 1788, and the Holey Dollar and Dump not struck until 1813, raises the question about the medium of currency operating in the intervening years.

No consideration had been given to the monetary needs of the penal settlement of New South Wales. It was planned on the assumption that it would be self-supporting, with no apparent need for hard cash for either internal or external purposes.

Even if it had been theoretically planned for, it would have been physically impossible for the British Government to fund this new venture.

Britain’s own currency was in a deplorable state and the Royal Mint’s priorities were clearly set at making improvements on the home front, not diverting hard cash off-shore.

Foreign coins arrived haphazardly in trade, and acquired local acceptability and brief legal recognition, but what was received quickly left the colony to pay for imports.

The essence of all business is a medium of exchange. Having very little hard cash, the inhabitants, from governor to free settlers and convicts, improvised by issuing hand-written promissory notes, in denominations as low as 3d, to settle their debts.

Commercial transactions were also facilitated through barter of goods and services. Philip Spalding, numismatist and author, presents a humorous account of the style (and cunning) of barter in the colony circa 1800 in his literary works, ‘The World of the Holey Dollar’.

“One lover of the drama, not having rum or flour presented at the theatre door a neatly-dressed haunch of kangaroo, which was accepted. To the infinite disgust of the manager, it was discovered to be a haunch of a favourite greyhound, belonging to an officer, which the fellow had stolen, killed off and passed off as kangaroo meat at 9d per pound.”

Liquor was the prime commercial force and medium for barter in the colony and for almost forty years was part of the wages received by a considerable section of the population.

An excerpt from the colony’s Official Records of 1803, clearly shows the citizens dependency on barter and promissory notes for facilitating commercial transactions and to a lesser extent the low denomination British copper currency of Mathew Boulton.

“It appears that Spirituous Liquors are the real measures of property, these and the Notes of Individuals almost the only circulating medium The Colony at present possesses no coin but that struck by Mr Boulton and sent out in 1800 and it consists of Farthings, Halfpence and Pence, each of which is issued at double its English nominal value, which has given an opportunity to the Birmingham coiners to exercise their ingenuity.”

Governor Lachlan Macquarie’s communication to Viscount Castlereagh on the 30th April 1810 re-affirmed the financial plight of the colony.

“In consequence of there being neither gold or silver coins of any denomination, nor any legal currency, as a substitute for specie in the colony, the people have been in some degree forced on the expedient of issuing and receiving notes of hand to supply the place of real money, and this petty banking has thrown open a door to frauds and impositions of a most grievous nature to the country at large”.

By 1812 the social fabric of Sydney as a community was emerging. It was no longer a redistribution point for convicts, with only the military as permanent residents.

Streets were being named. Macquarie, Phillip, Elizabeth, Castlereagh, Pitt and George Street. A post office was established and the common had been christened Hyde Park. Houses had to be aligned and numbered and heavy industry was being re-located out of the city centre to the suburbs.

Despite the social improvements, there was no bank and liquor remained the most commonly negotiated medium of currency exchange. Rum, which cost 7/6 a gallon was being sold for up to £8 and its use as a negotiating medium was utilized by all sections of the community, including government.

And the highest levels of Government at that. Even Lachlan Macquarie used rum to buy a house. The cost? 200 gallons. He furthermore gave the Government contract to construct the Sydney Hospital in 1811 to Messrs. Riley and Blaxcell and paid for it by granting a three-year monopoly in the spirit trade and the right to import 45,000 gallons of rum.

By 1812, the penal colony of New South Wales had shaken off the shackles of being a receptacle for convicts. It was no longer a ‘jail’. And was emerging as a structured society and a commercial hub.

The stage was set for Governor Lachlan Macquarie to introduce Australia’s first currency.

1813. The turning point. A coinage is conceived from Spanish Silver Dollars.

Governor Lachlan Macquarie etched his name into numismatic history forever when in 1812 he imported 40,000 Spanish Silver Dollars to alleviate a currency crisis in the infant colony of New South Wales.

Macquarie’s order for Silver Dollars did not specify dates. Any date would do. He wasn’t concerned about the various mints at which they were struck. Nor was he fussy about the quality of the coins. The extensive use of the Spanish Silver Dollar as an international trading coin meant that most were well worn.

Concluding that the shipment of 40,000 Spanish Silver Dollars would not suffice, Macquarie decided to cut a hole in the centre of each dollar, thereby creating two coins out of one, a ring dollar and a disc. It was an extension of a practice of ‘cutting’ coins into segments, widespread at the time.

Macquarie needed a skilled coiner to carry out his coining project. William Henshall, acquired his skills as an engraver in Birmingham, where the major portion of his apprenticeship consisted of mastering the art of die sinking and die stamping for the shoe buckle and engraved button trades. He was apprehended in 1805 for forgery (forging Bank of England Dollars) and sentenced to the penal colony of New South Wales for seven years.

Enlisted by Lachlan Macquarie as the colony’s first mint master, Henshall commenced the coining process by cutting out a disc from each silver dollar using a hand-lever punch.

He then proceeded to re-stamp both sides of the holed dollar around the inner circular edge with the value of five shillings, the date 1813 and the issuing authority of New South Wales. Other design elements in this re-stamping process included a fleur de lis, a twig of two leaves and a tiny ‘H’ for Henshall.

The holed coins were officially known as ring, pierced or colonial dollars and although ‘holey’ was undoubtedly applied to them from the outset, the actual term ‘holey’ dollar did not appear in print until the 1820s.

We refer to the coins today as the 1813 New South Wales Five Shillings (or Holey Dollar).

The silver disc that fell out of the hole wasn’t wasted. Henshall restamped the disc with a crown, the issuing authority of New South Wales and the lesser value of 15 pence and it became known as the Dump. The term ‘dump’ was applied officially right from the beginning; a name that continues to this day.

In creating two coins out of one, Macquarie effectively doubled the money supply. And increased their total worth by 25 per cent.

Anyone counterfeiting ring dollars or dumps were liable to a seven year prison term; the same penalty applied for melting down. Jewellers were said to be particularly suspect. To prevent export, masters of ships were required to enter into a bond of £200 not to carry the coin away.

Of the 40,000 silver dollars imported by Macquarie, records indicate that 39,910 of each coin were delivered to the Deputy Commissary General’s Office by January 1814 with several despatched back to Britain as specimens, the balance assumed spoiled during production.

The New South Wales colonial administration began recalling Holey Dollars and Dumps and replacing them with sterling coinage from 1822.

The Holey Dollar and Dumps remained as currency within the colony until 1829. The colony had by then reverted to a standard based on sterling and a general order was issued by Governor Darling to withdraw and demonetise the dollars and dumps. The recalled specie were eventually shipped off to the Royal Mint London, melted down and sold off to the Bank of England for £5044.

© Copyright: Coinworks