Governor Lachlan Macquarie etched his name into numismatic history forever when in 1812 he imported 40,000 Spanish Silver Dollars to alleviate a currency crisis in the infant colony of New South Wales.

Macquarie’s order for Silver Dollars did not specify dates. Any date would do. He wasn’t concerned about the various mints at which they were struck. Nor was he fussy about the quality of the coins. The extensive use of the Spanish Silver Dollar as an international trading coin meant that most were well worn.

Concluding that the shipment of 40,000 Spanish Silver Dollars would not suffice, Macquarie decided to cut a hole in the centre of each dollar, thereby creating two coins out of one, a ring dollar and a disc. It was an extension of a practice of ‘cutting’ coins into segments, widespread at the time.

Macquarie needed a man skilled in coin techniques to carry out his project. William Henshall acquired his skills as an engraver in Birmingham, where the major portion of his apprenticeship consisted of mastering the art of die sinking and die stamping for the shoe buckle and engraved button trades. He was apprehended in 1805 for forgery (forging Bank of England Dollars) and sentenced to the penal colony of New South Wales for seven years.

Enlisted by Lachlan Macquarie as the colony’s first mint master, Henshall commenced the coining process by cutting out a disc from each silver dollar using a hand-lever punch.

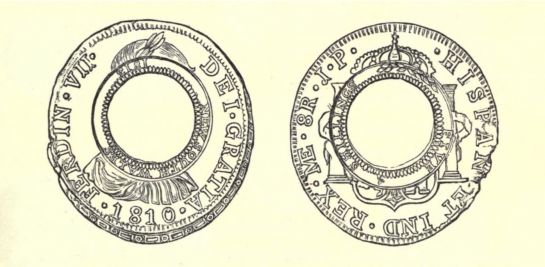

He then proceeded to re-stamp both sides of the holed dollar around the inner circular edge with the value of five shillings, the date 1813 and the issuing authority of New South Wales.

Other design elements in this re-stamping process included a fleur de lis, a twig of two leaves and a tiny ‘H’ for Henshall.

The holed coins were officially known as ring, pierced or colonial dollars and although ‘holey’ was undoubtedly applied to them from the outset, the actual term ‘holey’ dollar did not appear in print until the 1820s. We refer to the coins today as the 1813 New South Wales Five Shillings (or Holey Dollar).

The silver disc that fell out of the hole wasn’t wasted. Henshall restamped the disc with a crown, the issuing authority of New South Wales and the lesser value of 15 pence and it became known as the Dump. The term ‘dump’ was applied officially right from the beginning; a name that continues to this day.

In creating two coins out of one, Macquarie effectively doubled the money supply. And increased their total worth by 25 per cent.

Anyone counterfeiting ring dollars or dumps were liable to a seven-year prison term; the same penalty applied for melting down the coins. Jewellers were said to be particularly suspect. To prevent export, masters of ships were required to enter into a bond of £200 not to carry the coin away.

Of the 40,000 silver dollars imported by Macquarie, records indicate that 39,910 of each coin were delivered to the Deputy Commissary General’s Office by January 1814 with several despatched back to Britain as specimens, the balance assumed spoiled during production.

The New South Wales colonial administration began recalling Holey Dollars and Dumps and replacing them with sterling coinage from 1822.

The Holey Dollar and Dump remained as currency within the colony until 1829. The colony had by then reverted to a standard based on sterling and a general order was issued by Governor Darling to withdraw and demonetise the dollars and dumps.

The recalled specie was eventually shipped off to the Royal Mint London, melted down and sold off to the Bank of England for £5044.

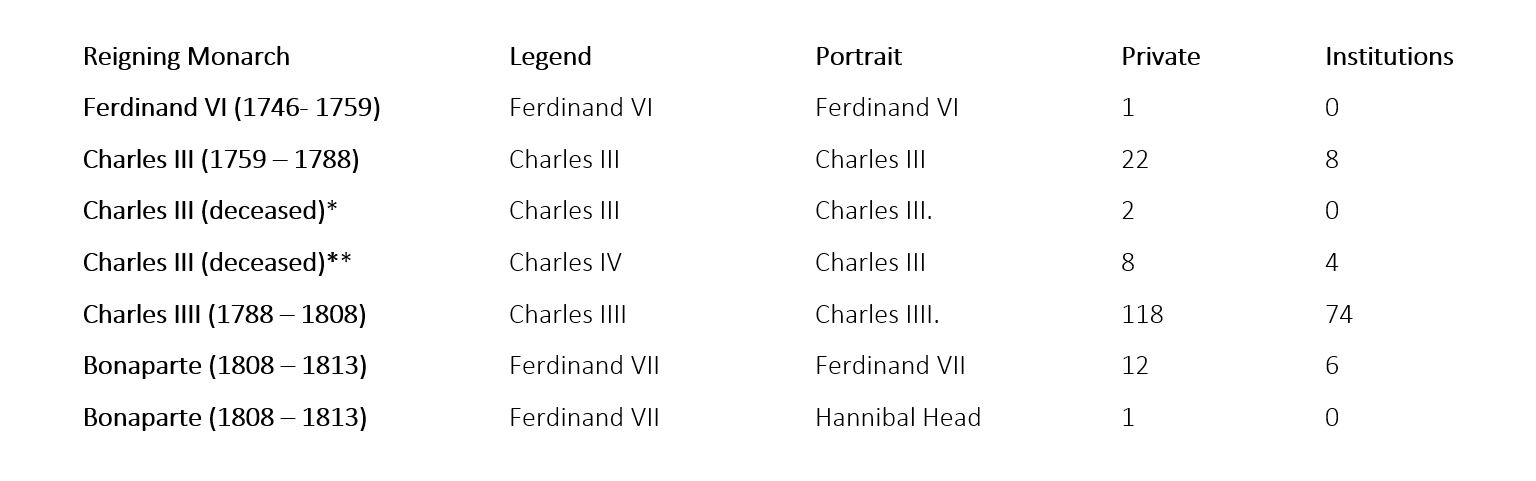

It is estimated that approximately 300 Holey Dollars exist today of which a third are held in public institutions with the balance owned by private collectors.