Original Treasury building, Adelaide.

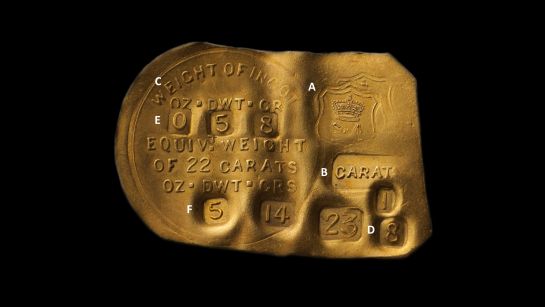

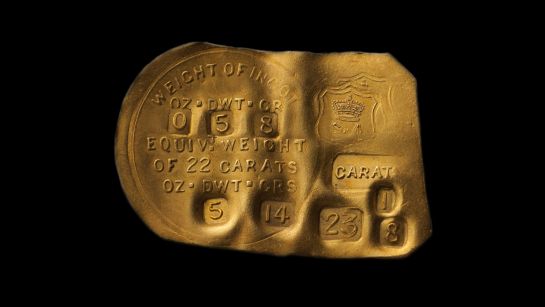

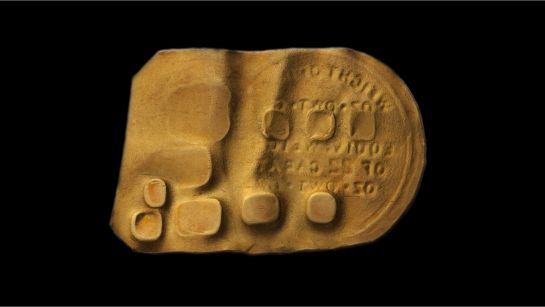

The Government Assay Office 1852 Gold Ingots are the very first gold pieces struck for currency purposes in the colonies of Australia, issued in South Australia under authority of the 1852 Bullion Act of the Province.

The Bullion Act was enacted on 28 January 1852 and remained in operation for twelve months. To ensure that the Government would have a steady supply of gold, its price was fixed for the duration of the Act at £3 11s per ounce.

The Ingots could be exchanged for banknotes at the rate of £3/11s per ounce. They could also be used by the banks to support their note issue, just as if they were gold sovereigns.

The discovery of significant gold deposits in Australia in 1851 created sudden wealth and stimulated immigration on a vast scale.

It had a profound impact on Australia’s social and political development and underpinned the abandonment of the penal system on which the settlement of Australia was based.

The new-found confidence and a vastly increased population encouraged a national sentiment that accelerated the Australian colonies to unite and form the Commonwealth of Australia in 1901.

It is one of the most eventful and extraordinary chapters in Australian history, transforming the economy and society and marking the beginnings of a modern multi-cultural Australia.

Word of the discovery of gold spread like wildfire across the country and overseas. First was the rush to Ophir near Bathurst in early 1851 and the even greater rush to Ballarat in August of the same year.

Then in quick succession came the rich finds throughout central Victoria, Queensland, Northern Territory and finally the bonanza in Western Australia.

No colony was immune from the dramatic effects of the discovery of gold.

Those that were rich in gold. And those, such as the colony of South Australia, that was devoid of the precious metal. Its economy collapsed due to the mass exit of manpower lured to the Victorian gold fields.

Adelaide lost almost half its male population within the first three months of the first big gold strike near Ballarat. Also gone its cash resources. About two-thirds of the available coin travelled out of the state.

As the two main pillars of national activity, labour and capital, literally walked out, prices plummeted, property plunged, mining scrip nosedived, and Adelaide took on the air of a ghost town, with row after row of tenantless houses.

The cash-strapped banks pressed their debtors for cash payments, but as most debtors were merchants with their capital tied up, disaster beckoned.

By late 1851, genuine panic gripped those who had stayed behind as the total and complete insolvency of Adelaide looked real.

Out of desperation the Government offered a reward of one thousand Pounds for the discovery of a gold field in South Australia. None was found.

South Australia’s problems were further compounded because there was no method available to convert the gold nuggets the diggers had brought back from Victoria into a form that could be used for monetary transactions.

Calls were made for the establishment of a Government mint and the issuing of a coinage, but this was viewed as being in direct violation of the Royal Prerogative. Coining was beyond the powers and privileges of any local authority.

On 9 January 1852, over 130 leading businessmen met with a further 166 merchants met with Lieutenant Governor Sir Henry Young and pressured him to start up a mint to convert the raw gold into coin. The intention was that the mint would purchase gold from the Victorian fields at a higher price than paid in Melbourne.

There are some doubts as to who suggested an Assay Office and stamped bullion. What is known is that the establishment of a similar office had been introduced into the legislature of New South Wales in 1851. It was defeated mainly due to the opposition of the banks.

What is also known. Robert Richard Torrens, the Colonial Treasurer, was an active and strong supporter of the proposal.

Although Young realised that only Royal approval could initiate a move to establish a mint, he was also aware that the survival of the colony was at stake.

He found a loophole in the legislation. While the Governors were not allowed to assent in her majesty’s name to any bill affecting the currency of the colony, an accompanying paragraph that stated … “unless urgent necessity exists requiring such to be brought in to immediate operation”.

The “urgent necessity” clause paved the way for the South Australian Legislative Council to pass the 1852 Bullion Act.

A special session of the Legislative Council was convened on the 28 January 1852.

An enactment was proposed that allowed the Assaying of gold into ingots; the Council seeking to deflect Royal disapproval by striking gold ingots rather than sovereigns.

The ingots were intended to form a currency that would back the banknote issues of the banks as if they were gold coin. And be used by the banks to increase their note circulation based on the amount of assayed gold deposited.

The Act was as daring, as it was contentious, in that it made the banknotes of the three South Australian banks a Legal Tender, under specified conditions.

It drew condemnation from the eastern states. Melbourne’s Argus condemned the Act as dangerous, radically unsound and interfering with the natural laws of commerce. But these protests were motivated by self-interest, as South Australia posed a real threat to the Victorian economy by re-directing capital and labour away from the Victorian gold fields.

The Bullion Act No 1 of 1852 has a record unique in Australian history. A special session of Parliament was convened to consider it. Parliament met at noon on the 28 January 1852. The Bill was read and promptly passed three readings and was then forwarded to the Lieutenant Governor and immediately received his assent.

It was one of the quickest pieces of legislation on record, with the whole proceedings taking less than two hours.

Thirteen days after the passing of the Act, on 10 February 1852, the Government Assay office was opened. Its activities were supported by a state government initiative to provide armed escorts to bring back the gold from the Victorian diggings.

By the time the first escort arrived, a second assay office had been established, and Joshua Payne was appointed die-sinker and engraver. By the end of August 1852, over £1 million worth of gold had been received at the assay offices.

The passing of the Bullion Act was a masterly stroke of legislature and played no small part in averting economic catastrophe and laying the foundation for a stabilised currency.

Leading numismatic author Greg McDonald expressed his views when he wrote. “That Australia is today viewed as one of the most desirable destinations on the planet is due, in no small part, in the ability of our forefathers to find an often analytical solution to a problem. The creation of these golden relics is a part of that ”can-do” ability that forged this nation”.