Radio personality, Ed Phillips, talks to MD of Coinworks, Belinda Downie, and explores the notion that decimalisation in 1966 gave Australia the opportunity to "go its own way".

The idea of Australia changing to decimal currency was first mooted in 1902. And revisited again in 1937, when a Royal Commission recommended Australia consider going decimal. It wasn’t until the 1950’s that the decimal currency movement gained momentum.

In 1958 Sir Robert Menzies included in his election platform the decimalisation of Australia's currency system.

While Menzies became side tracked with other more pressing issues, it was his Treasurer Harold Holt that took up the gauntlet and established the Decimal Currency Committee, headed by Sir Walter Scott (of W. D. Scott Management Consultant fame) in 1959.

Holt believed that there was an economic importance of converting Australia’s currency into a decimal system. That Australia would keep up with its trading partners and the overwhelming majority of the world.

But research also showed that the £30 million cost of converting to decimal, would soon be offset by an estimated £11 million annual saving to the Australian economy. The argument for converting to decimal wasn’t just a question of personal convenience, but of national productivity. The Australian pound, like its British counterpart, was divided into 20 shillings of 12 pence each, making the arithmetic of financial transactions unnecessarily difficult.

A currency system based on a unit 10 to the 100 was far less complicated, and made public reaction positive to the change.

The only compelling argument against decimalisation at the time, was the Australian pound’s symbolic connection to Britain. But it was noted that in the years following the Second World War, Australians were feeling less connected to the mother country.

The Decimal Currency Commitee reported in 1962, three years after it was established. And in 1963 the Government passed the Currency Act which nominated 14th February 1966 as Changeover Day or ‘C-day’ as it became known.

The Federal Government assessed that 1,700,000,000 coins would be required for decimalisation. And that a brand new mint was required.

Approval for construction of the Royal Australian Mint, to be located in Deakin, Canberra was granted in 1962 with work commencing in 1963.

It was decimalisation’s greatest single expenditure, with the building and fit-out totalling $9 million.

The Mint opened on 22 February 1965, a good year ahead of C-Day, and with help from the Royal Mint in London and its branches in Australia, was able to produce and stockpile about one billion coins ahead of decimal changeover.

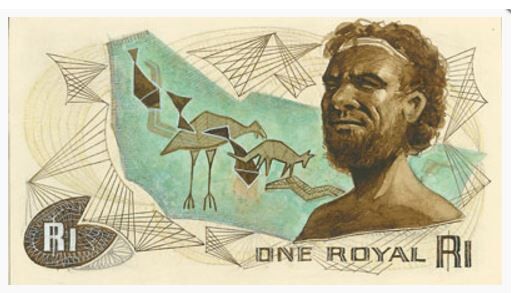

The Dollar was chosen. But it could have been the Royal. The Melba. Or the Anzac.

The Government announced a competition for the naming of our new currency, seeking suggestions from the public that had an Australian flavour.

‘Auster’ was the name suggested by Holt.

Suggestions were as bizarre as ‘Magpie, Noodle, Pacific, Tasma, Anzac, Brumbie, Melba, Koala, Kanga, Roo, Emu and Merino’.

Politicians names were also considered. Can you imagine? Make that five 'Shortens' please! Or just give me six 'Turnbulls'!

In June 1963, Menzies, ever the monarchist, rejected all of the entrants in favour of the ‘Royal’.

Between June and September, the Bank’s Note Printing Branch developed a variety of design concepts for the ‘Royal’ notes, interestingly some labelled as ‘Reserve Bank of Australia’ rather than ‘Commonwealth of Australia’. (See photos at right)

The ‘Royal’ met with widespread disapproval (particularly from the Labor Party), and on 19th September 1963, Holt conceded that the name of our currency unit would indeed be the ‘Dollar’.

Coin and note designs that reflected our national identity.

Treasury commissioned six accomplished designers for a limited competition, who were each to prepare a set of designs for the 1c, 2c, 5c, 10c, 20c & 50c coins. Seen as a rising young designer, Stuart Devlin was approached by a member of the Advisory Committee on Coin Design, Professor Joseph Burke, and urged Stuart to take part. He was hesitant, being 15 years younger than his competitors, and not trained in low relief work.

Initially Devlin’s work was ‘absolutely slated’ by fellow designers, and he nearly withdrew from the competition as a result. His decision to hang in there and work with the concept of Australian Fauna (which he felt gave an overall picture of what Australia was like), paid off. Rather than selecting designs of subjects such as maps, the Southern Cross or the Endeavour, the advisory panel saw an advantage of a ‘family’ of coins, and chose Devlin’s work.

Fellow competitor Gordon Andrews, eventual designer of the decimal notes, praised Devlin’s animal theme as ‘charming and sensitively realised’. The designs were widely seen as ‘capturing the air of change and opportunity prevailing in Australia in the 1960’s’.

In April 1964, designs by Andrews’ were accepted for the $1 $2, $10 and $20 notes which incorporated portraits and designs supplied from institutions such as the Mitchell Library, Royal Botanic Gardens and Qantas.

His designs also captured the young country’s history and contribution to the wider world, and gave prominent recognition to Aboriginal Culture, Women, Australia’s unique environment, Architecture and the arts and Aeronautics.

Interestingly, the only ‘living’ person depicted on our notes was the Queen.

To make the transition easier for users, the decimal denomination notes matched their pound/shilling/pence counterparts. The one dollar note replaced the ten shilling note, the two dollar note replaced the one pound, the ten dollar replaced the five pound, and the twenty dollar replaced the ten pound note.

Another aid used to help Australian’s increase acceptance of the new currency, was to maintain the pre-decimal note colours, and transfer them to the decimal design. The overall look and feel of the new notes was radically different to anything Australians had seen before.

The same thinking was applied to our coins, where colour, size and weight were the same as their predecessors.

The One and Two cent pieces (while smaller) represented the Penny and Half Penny, and the twenty, ten and five cent coins represented the florin, shilling and sixpence. The threepence was the loose thread and the only coin with no direct conversion. Considered too small by Government, the coin disappeared.

With the exception of the fifty cent piece, all of the ‘silver’ coins were struck from cupro-nickel, a metal initially trialled in Australia back in 1921 for the square penny.

The addition of the round fifty cent piece was controversial on several levels. The public and numismatists certainly believed it was not warranted or needed.

- There was confusion between the 20 and 50 cent pieces.

- It had no pre-decimal equivalent.

- And it was struck from .800 fine silver, the only decimal circulating coin to be struck from a precious metal.

The RAM struck over thirty-six million fifty cent rounds before rising silver prices halted production. Only fourteen million were released into circulation.

Hoarding of the fifty cent round became a national pastime and today, a 1966 fifty cent round is worth between six and ten dollars.

During the silver boom of the 1980’s they were fetching between eleven and fifteen dollars each.

A nation well prepared.

Decimalisation presented major logistical challenges. Designs and production for notes and coins had to be finalised, staff in the finance sector had to be trained, and everything from cash registers to petrol pumps had to be converted.

Courtesy of National Film and Sound Archive of Australia.

It also demanded a major public awareness campaign that had to firstly convince the Australian public of the value of decimalisation, then reassure them that the transition would be carried out as smoothly as possible.

It also had to educate people about how to convert prices.

All of this was overseen by the Decimal Currency Board, headed by Sir Walter Scott, whose regular appearances on national television offered reassurance about technicalities of the change.

But the real poster boy for the board’s publicity campaign was Dollar Bill, a cartoon figure that appeared in every conceivable media for the two years prior to C-Day. This included a TV advertisement called 'Dollar Bill and Australians Keep the Wheels of Industry Turning.'

The famous jingle was sung to the tune of ‘Click go the Shears’.

Dollar Bill also made regular appearances in newspaper comic strips and crosswords, booklets, brochures and letters.

Decimalisation met with some resistance among sections of the public adverse to change, but ultimately it was an easy sell for the board. People were given plenty of time to get used to the idea of decimalisation, every issue that would arise from the process was explained and addressed, and ultimately it was hard to argue against its merits.

Vending machines have always been a major headache as far as currency changes are concerned. Back in the 1920s the then Labor Government muted Square coinage. Vending machines was one of the prime reasons it was canned.

Compensation to vending machine operators was part of the compensation package given to those affected by the decimal currency changeover in 1966.

The introduction of decimal currency was a massive logistical exercise that involved the secret delivery of 600,000,000 coins from the Australian and London Mint to banks. And 150,000,000 banknotes.

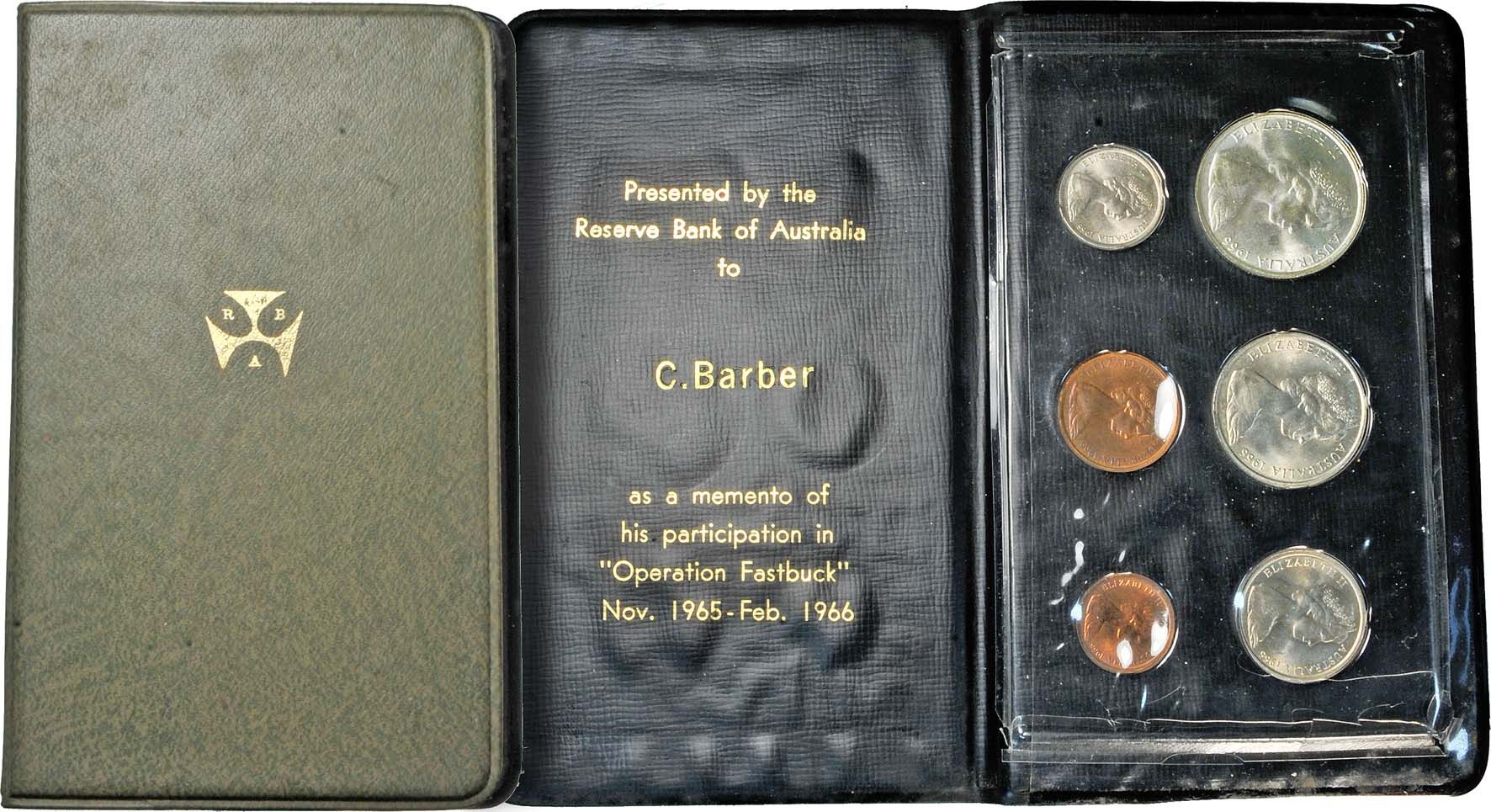

‘Operation Fast Bucks’ began three months preceding C-day, and saw hand-picked, well-armed police escort dozens of semi-trailers across the country, stocking the nation’s banks with the new currency.

One of the colourful stories to come out of this era is from a retired policeman. He recalls catching up with a friend (also a fellow policeman) who was part of the security detail transiting currency across the land.

For his involvement, the government gifted him a specially prepared wallet with all the new decimal coins in it.

He recalls meeting at the pub. And very thirsty they decided to break out the currency from the wallet and use it to acquire a few pots of beer.

Bad choice. Today the ‘Operation Fast Bucks Wallet’ is worth $1500! That's if you can find one.

The value of Collectables .....

The nation welcomed in C-Day.

C-Day came and went with the minimum of inconvenience. A major achievement.

Banks had closed four days earlier so they could convert their machinery and processes.

And when they opened on Monday 14th February, they were able to immediately begin issuing the new currency to long queues of enthusiastic or simply curious Australians.

Newspapers reported that even the Decimal Currency Board was surprised by how smoothly things went.

In five hours of trading on 17 February 1966, 48 tons of pennies were returned to the Bank of New South Wales alone.

The conversion programme was tipped to take two years but was completed in 18 months.

The old currency was tipped to circulate for 2 years but again the majority was returned in 18 months.

The changeover inspired a decimal coin collecting industry.

But it also further stimulated an already established pre-decimal coin collecting market, as people became concerned that treasures were going to be removed from their reach and withdrawn.

© Copyright: Coinworks