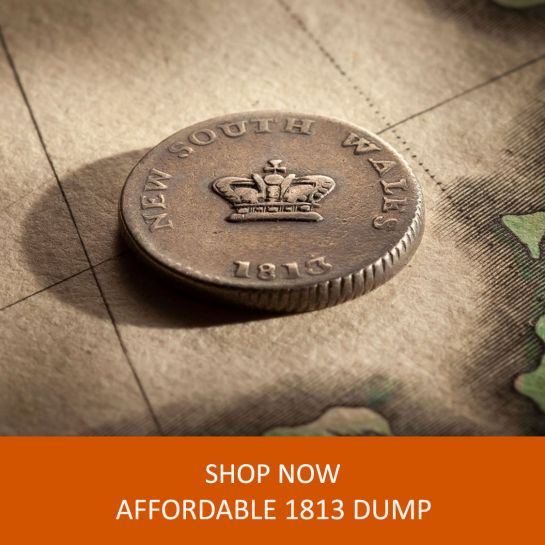

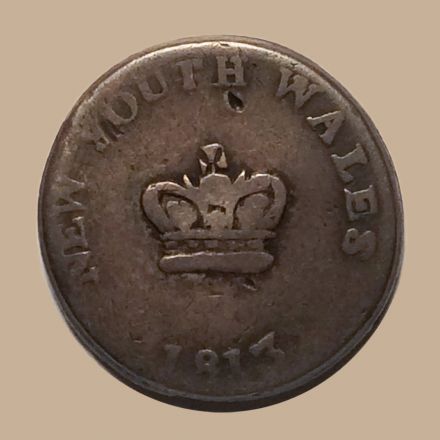

The 1813 Dump is the nation's first coin and the partner to the 1813 Holey Dollar. Find out more about this classic Australian rarity.

The Dump (and the Holey Dollar) are the nation’s first coins, minted in 1813 by order of Governor Lachlan Macquarie to provide a medium of exchange in the penal colony of New South Wales. The coins are national treasures and are revered and sought after by collectors the world over.

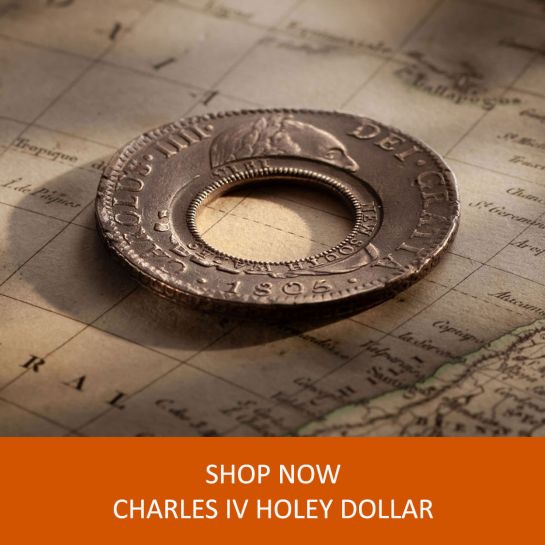

As Macquarie had no access to metal coin blanks to create his currency, he improvised and acquired 40,000 Spanish Silver Dollars as a substitute for blanks. To make his new coinage unique to the colony he employed emancipated convict William Henshall to cut a hole in each silver dollar, thereby creating two coins out of one. The holed dollar was over-stamped around the edge of the hole with the date 1813, the value Five Shillings and the issuing authority of New South Wales. It became the illustrious Holey Dollar.

The silver disc that fell out of the hole was not wasted. It was over-stamped with the date 1813, the issuing authority of New South Wales and the value fifteen pence and became the equally illustrious Dump.

While the original intention was to create 40,000 Holey Dollars and 40,000 Dumps from 40,000 silver dollars, spoilage and the despatch of samples back to Great Britain saw a slightly reduced number of Holey Dollars and Dumps - 39,910 of each - released into circulation.

Today there are approximately 800 Dumps available to collectors with perhaps 200 held in museums. The best thing about the Dump is that each and every coin is different. No two coins are the same.

Bacon and eggs. Fish and chips. Laurel and Hardy. Batman and Robin. One without the other is incomplete. And so it is with the Holey Dollar and Dump. Experience has shown us that most Dump buyers will eventually pursue a Holey Dollar … and vice versa. A simple reflection of the collector’s psyche for completion.

The buyer that pursues a top quality Dump will find the task extremely challenging. It can be years before a premium quality example comes onto the market and decades before the very best becomes available. And that statement is said in the knowledge that there are perhaps 800 Dumps, across all quality levels, available to private collectors.

The Dump with a value of fifteen pence circulated widely in the colony, the extreme wear on most Dumps evidence that they saw considerable use. The Holey Dollar being a higher valued piece, at five shillings, had a narrower band of circulation.

So, while the Dump may seem the diminutive partner of the Holey Dollar, the reality is top quality Dumps have authority. They are extremely rare, in fact far rarer than their holed counterpart in the same quality level. As such, Dumps are highly valued.

Historians have drawn evidence from Bank of New South Wales records to support this view. Official records show that in 1820 the bank held 16,680 Holey Dollars and only 5900 Dumps. Considering that 39,910 of each were released into circulation, the figures reflect the greater circulation of the smaller denomination Dump.

Useful information if you are buying an 1813 Dump.

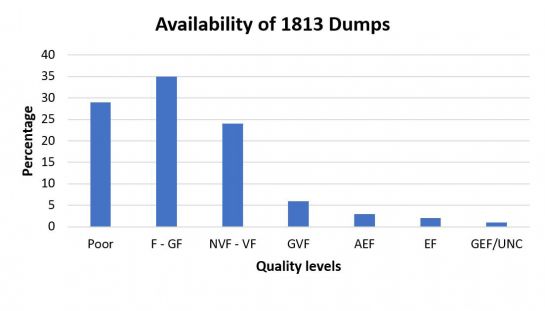

It is an interesting exercise to look at the availability of Dumps and their current market values with an acknowledgment that there is a vast price difference between a well circulated 1813 Dump and one in the upper echelons of quality.

But the information that we have gleaned from our research clearly shows the reasons why. Top quality Dumps are exceedingly rare.

You can acquire a well used 1813 Dump for $5,000 to $10,000. Of course you won’t see much of the design, it will almost be obliterated.

Moving up the quality scale you will find a Fine to good Fine Dump for $15,000 to $25,000. The design will be evident, but flattened, and the coin will more than likely be knocked around. The reality is that finding examples below the $25,000 price level is a relatively easy task.

Buyers that are looking for a higher quality example might stretch their budget with the expectations of a $25,000 to $30,000 outlay and so walk away with an about Very Fine to Very Fine Dump.

The chart clearly shows that the 1813 Dump is reasonably readily available up to, and including, a quality level of Very Fine. What is also obvious from the chart is that Good Very Fine is the point at which extreme rarity kicks in.

The buyer that is looking for a high quality Good Very Fine Dump will have to extend their budget to $35,000 with perhaps an upper ceiling of $45,000. Acquiring a Dump at this quality level is not only about the dollars involved. Its about exercising a lot of patience for you can realistically be looking at a one-year time frame, perhaps even longer.

It is at the quality level of About Extremely Fine, and higher, that the task of finding a Dump becomes tough and challenging, invariably involving several years. And a price range upwards of $45,000.

The chart below clearly shows that at a quality level of About Extremely Fine to Extremely Fine you are in 'rarefied air' with very few examples becoming available. And that the quality ranges of Good Extremely Fine and up to Uncirculated are an absolute 'killer' for acquisition.

When it comes to selecting an 1813 Dump, quality is not the only deliberation. Others facets that should be considered are ....

Are the denticles evident?

A piece of art with out a picture frame is a blank canvas ... and so it is with a coin that has no edges. The denticles act like a picture frame to the coin giving it substance.

Can you see the oblique edge milling?

The edge milling was used as deterrent against clipping whereby the unscrupulous shaved off slivers of silver, reducing the silver content of the Dump. (And making a small profit on the side.)

Is there evidence of the original Spanish Dollar design?

While the Holey Dollar clearly shows that it is one coin struck from another, in a less obvious way so too can the Dump. There is no doubt that heat was involved in the creation of the Dump. When the disc fell out of the centre of the Spanish Dollar, it still bore the original dollar design of a four quadrant shield, housing a lion and castle in each quadrant. And the shield's cross-bars. High temperatures obliterated the original Spanish Dollar design from most examples. Those Dumps that retain the original dollar design elements are highly prized.

Is the elusive 'H' for Henshall present?

Mint Master William Henshall declared his involvement in the creation of the Dump by inserting an 'H' into some - but not all - of the dies used during its striking. Its presence on the reverse between the words 'FIFTEEN' AND 'PENCE' is highly prized.

The Dump ... not as simple as it looks.

As to how the Dump (and the Holey Dollar) were actually manufactured ... no one really knows. No documentation as to the method has ever been found.

It is safe to assume that whatever machinery was employed, it was hand operated as the first steam engine did not become operational in the colony until 1815.

Likely production options were the screw press, drop hammer or hand-held punch with the drop hammer method onto a pre-heated plug generally regarded as the most likely.

There is no doubt that heat was involved in the creation of the Dump. When the disc fell out of the centre of the Spanish Dollar, it still bore the original dollar design of a four quadrant shield, housing a lion and castle in each quadrant. And the shield's cross-bars.

High temperatures obliterated the original Spanish Dollar design from most examples. Those Dumps that retain the original dollar design elements are highly prized.

The high temperatures also caused an expansion of the metal disc that fell out of the dollar. The very reason why the Dump is always larger than the hole in the Holey Dollar.

The haphazard, obliquely grooved edge milling found on the dumps indicates that a 'fiddle method' was the final step in the production process whereby a roll of Dumps was rotated under pressure against a grooved cylinder.

The nation's first Mint Master, William Henshall, was determined to leave an indelible mark that declared his involvement in the creation of the nation's first coins and he did so by inserting his initial, an 'H' for Henshall, on some - but not all - of the reverse dies of the Dump.

Four distinct styles (or die combinations) of the Dump have been identified. The four styles have been classified by authors Mira and Noble as the type A/1, D/2, E/3 and C/4.

On the obverse, the different styles are reflected in the shape of the cross on the crown, the position of this cross in relation to the letters in the legend above it. And in the positioning of the row of jewels (or pearls) in the crown.

On the reverse, differences are found in the distances between the words 'FIFTEEN' and 'PENCE' and in the position of the 'T' in 'FIFTEEN' in relation to the 'N' in 'PENCE'.

No examples have been identified that differ from the four styles.

The most aesthetically pleasing Dump is that struck using the A/1 dies, which produced a coin that was well centred. Of the 800 Dumps that survive today, more than 70 per cent were struck using the A/1 dies.

The D/2 dies produced a coin that had some design shortcomings. Historians suggest that the D/2 dies were quite possibly the first combination used, for the D/2 examples invariably have partial edge denticles (or none at all) and a partially struck legend and date indicating that the die was too large for the silver disc. Of the 800 surviving Dumps 25 per cent were struck using the D/2 dies.

The E/3 and C/4 dies produced coins that were very crude and esoteric and tend to be enjoyed by collectors seeking to acquire one of each style. There is a suggestion that they may have been test pieces presented to Governor Macquarie before production began.

Many of the E/3 and C/4 Dumps have surface cracks and splits supporting the theory that they were used for trials while the correct striking pressure and planchet temperatures were being worked out. There are also some suggestions that they may have been contemporary forgeries. Irrespective, the E/3 and C/4 Dumps are extremely rare and an essential part of the 'Dump' story.

Type A/1, D/2, E/3 and C/4 - we explore the different styles of 1813 Dump.

Type A/1 Dump. Obverse Die A. Reverse Die 1.

The cross at the top of the crown points between the 'T & H' of 'SOUTH' in the legend. The '3' in '1813' tilts to the left.

Close-up of the Crown on the Type A/1 Dump.

There are five pearls in the band of the crown, three of which are the same size, the remaining two are smaller. The line of five pearls is on the diagonal with the left hand pearl touching the base of the band, the far right pearl touching the top of the band.

Type D/2 Dump. Obverse Die D. Reverse Die 2.

The cross at the top of the crown points between the 'U & T' of 'SOUTH' in the legend. A stop may be seen after 'NEW' and 'SOUTH' in the legend. The dies apparently had shallow depressions for these stops which soon filled with debris and can be difficult (or almost impossible) to discern on pieces even in reasonable condition.

Close-up of the Crown on the Type D/2 Dump.

The line of five pearls are in a straight line, equal in size and touch the top of the band. The '3' in '1813' tilts to the left.

Type E/3 Dump. Obverse Die E. Reverse Die 3.

The dies are poorly engraved and are considered an early effort. The top of the cross points between the 'T & H' of 'SOUTH' in the legend. The '3' in '1813' tilts to the left.

Close-up of the Crown of the Type E/3 Dump.

The cross at the top of the crown is noticeably lopsided, leaning to the left. The five pearls are irregular in shape, with the far left pearl touching the top of the band.

Type C/4 Dump. Obverse Die C. Reverse Die 4.

The dies show extensive re-cutting and poor engraving in both the legend and the crown. The top of the cross points between the 'T & H' of 'SOUTH' in the legend. The crown is enlarged and the 'N' in New and 'S' in 'SOUTH' have been dropped to a lower level. The '3' in '1813' is upright.

Close-up of the Crown on the Type C/4 Dump.

The cross at the top of the crown is noticeably lopsided, tilted slightly to the right. The five pearls are irregular in shape and central in the band.

Coinworks recommends

© Copyright: Coinworks