1788 – 1813. From penal colony to commercial hub. A nation emerges with its own coinage, the 1813 Holey Dollar and Dump.

That Australia was settled in 1788, and the Holey Dollar and Dump not struck until 1813, raises the question about the medium of currency operating in the intervening years.

No consideration had been given to the monetary needs of the penal settlement of New South Wales. It was planned on the assumption that it would be self-supporting, with no apparent need for hard cash for either internal or external purposes.

Even if it had been theoretically planned for, it would have been physically impossible for the British Government to fund this new venture.

Britain’s own currency was in a deplorable state and the Royal Mint’s priorities were clearly set at making improvements on the home front, not diverting hard cash off-shore.

Foreign coins arrived haphazardly in trade, and acquired local acceptability and brief legal recognition, but what was received quickly left the colony to pay for imports.

The essence of all business is a medium of exchange. Having very little hard cash, the inhabitants, from governor to free settlers and convicts, improvised by issuing hand-written promissory notes, in denominations as low as 3d, to settle their debts.

Ann Mash Promissory Note Circa 1812.

Commercial transactions were also facilitated through barter of goods and services. Philip Spalding, numismatist and author, presents a humorous account of the style (and cunning) of barter in the colony circa 1800 in his literary works, ‘The World of the Holey Dollar’.

“One lover of the drama, not having rum or flour presented at the theatre door a neatly-dressed haunch of kangaroo, which was accepted. To the infinite disgust of the manager, it was discovered to be a haunch of a favourite greyhound, belonging to an officer, which the fellow had stolen, killed off and passed off as kangaroo meat at 9d per pound.”

Liquor was the prime commercial force and medium for barter in the colony and for almost forty years was part of the wages received by a considerable section of the population.

Governor Lachlan Macquarie’s communication to Viscount Castlereagh on the 30th April 1810 re-affirmed the financial plight of the colony.

“In consequence of there being neither gold or silver coins of any denomination, nor any legal currency, as a substitute for specie in the colony, the people have been in some degree forced on the expedient of issuing and receiving notes of hand to supply the place of real money, and this petty banking has thrown open a door to frauds and impositions of a most grievous nature to the country at large.”

By 1812 the social fabric of Sydney as a community was emerging. It was no longer a redistribution point for convicts, with only the military as permanent residents.

Streets were being named. Macquarie, Phillip, Elizabeth, Castlereagh, Pitt and George Street. A post office was established and the common had been christened Hyde Park. Houses had to be aligned and numbered and heavy industry was being re-located out of the city centre to the suburbs.

Despite the social improvements, there was no bank and liquor remained the most commonly negotiated medium of currency exchange.

Rum, which cost 7/6 a gallon was being sold for up to £8 and its use as a negotiating medium was utilized by all sections of the community, including government.

And the highest levels of Government at that. Even Lachlan Macquarie used rum to buy a house. The cost? 200 gallons.

He furthermore gave the Government contract to construct the Sydney Hospital in 1811 to Messrs. Riley and Blaxcell and paid for it by granting a three-year monopoly in the spirit trade and the right to import 45,000 gallons of rum.

By 1812, the penal colony of New South Wales had shaken off the shackles of being a receptacle for convicts. It was no longer a ‘jail’. And was emerging as a structured society and a commercial hub.

The stage was set for Governor Lachlan Macquarie to introduce Australia’s first currency.

1813. The turning point. A coinage is conceived from Spanish Silver Dollars.

Governor Lachlan Macquarie etched his name into numismatic history forever when in 1812 he imported 40,000 Spanish Silver Dollars to alleviate a currency crisis in the infant colony of New South Wales.

Macquarie’s order for Silver Dollars did not specify dates. Any date would do. He wasn’t concerned about the various mints at which they were struck. Nor was he fussy about the quality of the coins. The extensive use of the Spanish Silver Dollar as an international trading coin meant that most were well worn.

Concluding that the shipment of 40,000 Spanish Silver Dollars would not suffice, Macquarie decided to cut a hole in the centre of each dollar, thereby creating two coins out of one, a ring dollar and a disc. It was an extension of a practice of ‘cutting’ coins into segments, widespread at the time.

Macquarie needed a skilled coiner to carry out his coining project. William Henshall, acquired his skills as an engraver in Birmingham, where the major portion of his apprenticeship consisted of mastering the art of die sinking and die stamping for the shoe buckle and engraved button trades. He was apprehended in 1805 for forgery (forging Bank of England Dollars) and sentenced to the penal colony of New South Wales for seven years.

Enlisted by Lachlan Macquarie as the colony’s first mint master, Henshall commenced the coining process by cutting out a disc from each silver dollar using a hand-lever punch.

He then proceeded to re-stamp both sides of the holed dollar around the inner circular edge with the value of five shillings, the date 1813 and the issuing authority of New South Wales. Other design elements in this re-stamping process included a fleur de lis, a twig of two leaves and a tiny ‘H’ for Henshall.

The holed coins were officially known as ring, pierced or colonial dollars and although ‘holey’ was undoubtedly applied to them from the outset, the actual term ‘holey’ dollar did not appear in print until the 1820s.

We refer to the coins today as the 1813 New South Wales Five Shillings (or Holey Dollar).

The silver disc that fell out of the hole wasn’t wasted. Henshall restamped the disc with a crown, the issuing authority of New South Wales and the lesser value of 15 pence and it became known as the Dump. The term ‘dump’ was applied officially right from the beginning; a name that continues to this day.

In creating two coins out of one, Macquarie effectively doubled the money supply. And increased their total worth by 25 per cent.

Anyone counterfeiting ring dollars or dumps were liable to a seven year prison term; the same penalty applied for melting down. Jewellers were said to be particularly suspect. To prevent export, masters of ships were required to enter into a bond of £200 not to carry the coin away.

Of the 40,000 silver dollars imported by Macquarie, records indicate that 39,910 of each coin were delivered to the Deputy Commissary General’s Office by January 1814 with several despatched back to Britain as specimens, the balance assumed spoiled during production.

The New South Wales colonial administration began recalling Holey Dollars and Dumps and replacing them with sterling coinage from 1822.

The Holey Dollar and Dumps remained as currency within the colony until 1829. The colony had by then reverted to a standard based on sterling and a general order was issued by Governor Darling to withdraw and demonetise the dollars and dumps.

The recalled specie were eventually shipped off to the Royal Mint London, melted down and sold off to the Bank of England for £5044.

It is estimated that 300 Holey Dollars exist today of which a third are held in public institutions with the balance owned by private collectors.

Every Holey Dollar is unique.

So let’s consider the 200 Holey Dollars held by private collectors.

Are any identical?

The 40,000 Spanish Silver Dollars imported by Macquarie were all different. Different dates, different monarchs, different mints and with a huge variance in quality.

Furthermore, the application of the counter stamps by William Henshall was haphazard.

By default therefore, each Holey Dollar is different. No two are the same. Each is unique.

The influence of the monarch and mint on the rarity - and value - of a Holey Dollar.

When Macquarie ordered the silver dollars, he did not specify dates. Silver Dollars minted under Ferdinand VI, Charles III, Charles IIII and Ferdinand VII were all acceptable. Nor did he care where they were minted, Mexico, Peru, Bolivia or Spain.

Nor was he fussy about the quality of the coins. The extensive use of the Spanish Silver Dollar as an international trading coin meant that most were well worn.

Nor was Henshall selective when he picked a silver dollar out of a barrel and hammered out the disc in the centre. We also know that the over stamping process was haphazard. Quality control was not a high priority.

And while no two Holey Dollars are the same, they can be grouped into types based on the monarch and the mint of the original silver dollar.

About 75 per cent of Holey Dollars were converted from Silver Dollars produced during the reign of Charles IIII. Holey Dollars converted from Silver Dollars from the earlier Charles III era and later Ferdinand VII era are extremely rare. The Holey Dollar of Ferdinand VI is unique.

As the Mexico Mint was a prolific producer of silver coinage, it comes as no surprise that about 77 per cent of Holey Dollars were converted from Mexico Mint Silver Dollars. Of the remaining mints, 11 per cent pertain to Lima, 10 per cent to Potosi. And one only to the Madrid Mint.

The table below details the spread of privately held Holey Dollars broken down by date (or monarch) and mint.

| Legend | Mexico Mint | Lima Mint | Potosi Mint | Madrid Mint |

| Ferdinand VI | 1 | |||

| Charles III | 19 | 4 | 1 | |

| Charles IIII | 115 | 16 | 14 | 1 |

| Ferdinand VII | 12 | 1 | ||

| Classification by Monarch and Mint of known surviving Holey Dollars held in private hands | ||||

The influence of quality on the rarity - and value - of a Holey Dollar.

Unlike today’s obsessive collectors – and rightly so – Macquarie wasn’t fussy about coin quality. He was a pragmatist – he had to be – determined to increase the supply of money in circulation.

The majority of Silver Dollars that he imported were well worn reflecting the Dollars extensive use as an international trading coin.

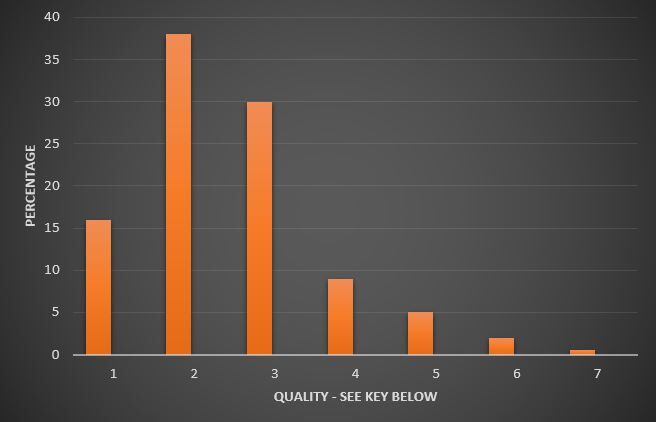

The chart below details the quality variance of the 200 surviving Holey Dollars held in collector’s hands.

- Fair – Good. Heavily circulated, and akin to a washer.

- About Fine – Good Fine. Well circulated, knocked around and design details partially worn away.

- About Very Fine to Very Fine. Circulated with some elements of the design worn down.

- Good Very Fine. Circulated with design details slightly worn.

- About Extremely Fine – Extremely Fine. Slight wear. Design details intact.

- Good Extremely Fine. Well preserved and the slightest hint of wear.

- Uncirculated. The coin has not undergone any circulation.

What is obvious from this chart is that 93 per cent of Holey Dollars show visible signs of wear; wear that is clear to the naked eye.

Only 7 per cent of surviving Holey Dollars show minimal wear with only one example listed as Uncirculated.

Final assessment of a Holey Dollar.

The Holey Dollar is a complicated beast. It is Australia’s most intriguing coin and there are many factors that affect its value.

Quality obviously plays a part: the quality of the original Spanish Silver Dollar and the quality of the counter stamps.

But the value of a Holey Dollar is also influenced by the mint and monarch of the original Spanish Silver Dollar.

Complicated? Perhaps. Challenging? Yes. Irrespective, the Holey Dollar is the jewel in the crown of every Australian coin collection.

© Copyright: Coinworks