The Government Assay Office Gold Ingots are definitively the point at which gold coin history began in Australia. They are the very first gold pieces struck for currency purposes in the colonies of Australia and were minted in 1852 from gold dug from the Victorian gold fields.

How one state's misfortune created a lasting legacy of the Adelaide Pound.

Leading numismatic author Greg McDonald expressed his views when he wrote. “That Australia is today viewed as one of the most desirable destinations on the planet is due, in no small part, in the ability of our forefathers to find an often analytical solution to a problem. The creation of these golden relics is a part of that ”can-do” ability that forged this nation”.

Ah, what a year it was in 1852 - what momentous events were happening in that year! A small sampler for history buffs:

Louis Napoleon took his throne as the head of the Second French Empire.

Harriet Beecher Stowe's "Uncle Tom's Cabin" was published – as was the first edition of Roget's Thesaurus.

The now-famous cartoon figure of Uncle Sam made his first appearance.

Oh, yes … and Emma Snodgrass was arrested in Boston for wearing pants!

Meanwhile, in the far-off colony of South Australia, a humble gold coin was minted. Its face value was one Pound.

It’s accepted wisdom that the gold rush that brought people and prosperity to Victoria and New South Wales in the mid-19th Century was good for everyone. However, for the people of South Australia, it could well have signalled a catastrophe. It took a master stroke on the part of that state’s legislators to avert disaster and lay the foundations for a stabilised currency in the young colony. It also led to the creation of Australia’s first gold coin, the Adelaide Pound.

In 1850 South Australia was, like any fledgling colony, struggling to find its feet after the inevitable financial difficulties of its foundation years. With a population reaching 50,000, burgeoning mining, agricultural and pastoral industries, and an estimated cash value of £211,480, there was an air of increasing prosperity.

This, however, masked an over-confidence that resulted in rising prices, high wages, unwise speculation and an over-stocking by merchants.

For those who cared to see it, the year 1851 opened up with all the portents of a coming crisis. The discovery of gold in NSW led some of the more venturesome males to strike out for the diggings; when the Victorian goldfields opened up the following year, the trickle became a flood, and by March 1852 over 8,000 of the menfolk had gone east, taking with them not only manpower but also cash resources - about two-thirds of the available coin travelled out of the state.

As the two main pillars of national activity, labour and capital, literally walked out, prices plummeted, property plunged, mining scrip nosedived, and Adelaide took on the air of a ghost town, with row after row of tenantless houses.

It got worse. The cash-strapped banks pressed their debtors for cash payments, but as the majority of debtors were merchants with their capital tied up – disaster beckoned.

The general pessimism lessened in January 1852, when about £50,000 worth of gold arrived in the colony. Even so, on account of the scarcity of coin the merchants and banks were forced to accept gold dust in payment for goods.

Calls were made for the establishment of a mint and the issuing of a coinage, but this was seen as being in direct violation of the Royal Prerogative – the colony had no authority to mint and issue coins. In desperation a reward of one thousand Pounds was offered for the discovery of a gold field in SA.

Then came the Bullion Act - one of the quickest pieces of legislation on record, with the whole proceedings taking less than two hours. It was an invasion of the Royal Prerogative and a blatant interference with the currency, but it saved the South Australian colony from insolvency.

In short, the Act allowed the receiving, assaying and stamping of gold into ingots. The ingots were never intended to form a currency, but could be used by the banks to increase their note circulation, based on the amount of assayed gold deposited.

The Government Assay Office Gold Ingots are definitively the point at which gold coin history began in Australia. They are the very first gold pieces struck for currency purposes in the colonies of Australia and were minted in 1852 from gold dug from the Victorian gold fields.

The Act compelled the banks to increase their note circulation to meet all assayed gold deposited, effectively depriving them of control over their currency issues. The notes were payable in Sterling or coin, which put huge pressure on the banks to import sovereigns to support their note issues. Sudden termination of the Act could mean temporary insolvency if the banks had insufficient Sterling or coin to redeem their notes.

Needless to say it didn’t receive unanimous approval in South Australia, with the Bank of Australasia declining to issue notes in exchange for ingots. This placed a huge burden on the other two banks.

Neither was there support from the eastern states: Melbourne’s Argus condemned the Act as dangerous, radically unsound and interfering with the natural laws of commerce. But these protests were motivated by self-interest, as South Australia posed a real threat to the Victorian economy by re-directing capital and labour away from the Victorian gold fields.

The first Assay Office opened on 10 February 1852. Its activities were supported by a state government initiative to provide armed escorts to bring back the gold from the Victorian diggings. By the time the first escort arrived, a second assay office had been established, and Joshua Payne was appointed die-sinker and engraver. By the end of August 1852, over £1 million worth of gold had been received at the assay offices.

In the second Annual Report of the Chamber of Commerce, the value of the Bullion Act was summed up in the following words:

“The effect of this measure was little short of miraculous. Credit and confidence was restored, the extreme tightness in the money market was relieved, and the public mind was at once raised from a state of paralysing despondency to one of hopefulness and vigour. In its more permanent results, the measure has greatly exceeded the expectations which were formed of it.”

In his opening address of the third session of the Legislative Council on 1 September, the Lieutenant Governor stated:

“The Bullion Act has up to the present time in its practical results, almost compensated for the absence of a mint, has surpassed the expectations of the most sanguine and has completely vindicated the prudence and sagacity of the Legislature of SA.”

But the banks were still under enormous pressure, being forced to import sovereigns to meet the extent of their note circulation. On 23rd November 1852 the government responded to agitation from both the banks and the public for the coining of gold tokens, and passed the second part of the Bullion Act. Within a week 600 coins (Adelaide Pounds) had been delivered to the SA Banking Company, 100 of which were sent to London.

By this time, however, the Act had only three months left to run, so the relatively small number of 24,768 coins were minted at the Assay Office and delivered to the banks. Of those, very few were actually circulated. When it was discovered that the intrinsic value of the gold contained in each piece exceeded its nominal value, the vast majority were promptly exported to London and melted down!

That goes a long way towards explaining why so few Adelaide Pounds survive today – and why the highest-quality examples command such high prices. That, and the fact that Australians are at last developing some pride in their own rich history.

Gold’s discovery in Australia led the nation on a progressive historical and financial journey that gave Australia increased recognition and a burgeoning position in the world, transforming the economy and society and marking the beginnings of a modern Australia.

The first to feel gold’s impact was South Australia, with the economy collapsing due to the exit of labour and circulating currency to Victoria’s gold fields.

Adelaide lost almost half its male population within the first three months of the first big gold strike near Ballarat. The Adelaide economy was as good as bankrupt.

South Australia’s problems were further compounded because there was no method available to convert the gold nuggets the diggers had brought back from Victoria into a form that could be used for monetary transactions. The South Australian Legislative Council was prohibited from striking coins at it did not have Royal Prerogative from London.

However, an “urgent necessity” clause paved the way for the South Australian Legislative Council to pass the 1852 Bullion Act within two hours. The Council sought to deflect Royal disapproval by striking gold ingots rather than coins.

The Government Assay Office 1852 Gold Ingots are the very first gold pieces struck for currency purposes in the colonies of Australia, issued in South Australia under authority of the 1852 Bullion Act of the Province.

The Bullion Act was enacted on 28 January 1852 and remained in operation for twelve months. To ensure that the Government would have a steady supply of gold, its price was fixed for the duration of the Act at £3 11s per ounce.

The Ingots could be exchanged for banknotes at the rate of £3/11s per ounce. They could also be used by the banks to support their note issue, just as if they were gold sovereigns.

The discovery of significant gold deposits in Australia in 1851 created sudden wealth and stimulated immigration on a vast scale.

It had a profound impact on Australia’s social and political development and underpinned the abandonment of the penal system on which the settlement of Australia was based.

The new-found confidence and a vastly increased population encouraged a national sentiment that accelerated the Australian colonies to unite and form the Commonwealth of Australia in 1901.

It is one of the most eventful and extraordinary chapters in Australian history, transforming the economy and society and marking the beginnings of a modern multi-cultural Australia.

Word of the discovery of gold spread like wildfire across the country and overseas. First was the rush to Ophir near Bathurst in early 1851 and the even greater rush to Ballarat in August of the same year.

Then in quick succession came the rich finds throughout central Victoria, Queensland, Northern Territory and finally the bonanza in Western Australia.

No colony was immune from the dramatic effects of the discovery of gold.

Those that were rich in gold. And those, such as the colony of South Australia, that was devoid of the precious metal. Its economy collapsed due to the mass exit of manpower lured to the Victorian gold fields.

Adelaide lost almost half its male population within the first three months of the first big gold strike near Ballarat. Also gone its cash resources. About two-thirds of the available coin travelled out of the state.

As the two main pillars of national activity, labour and capital, literally walked out, prices plummeted, property plunged, mining scrip nosedived, and Adelaide took on the air of a ghost town, with row after row of tenantless houses.

The cash-strapped banks pressed their debtors for cash payments, but as most debtors were merchants with their capital tied up, disaster beckoned.

By late 1851, genuine panic gripped those who had stayed behind as the total and complete insolvency of Adelaide looked real.

Out of desperation the Government offered a reward of one thousand Pounds for the discovery of a gold field in South Australia. None was found.

South Australia’s problems were further compounded because there was no method available to convert the gold nuggets the diggers had brought back from Victoria into a form that could be used for monetary transactions.

Calls were made for the establishment of a Government mint and the issuing of a coinage, but this was viewed as being in direct violation of the Royal Prerogative. Coining was beyond the powers and privileges of any local authority.

On 9 January 1852, over 130 leading businessmen met with a further 166 merchants met with Lieutenant Governor Sir Henry Young and pressured him to start up a mint to convert the raw gold into coin. The intention was that the mint would purchase gold from the Victorian fields at a higher price than paid in Melbourne.

There are some doubts as to who suggested an Assay Office and stamped bullion. What is known is that the establishment of a similar office had been introduced into the legislature of New South Wales in 1851. It was defeated mainly due to the opposition of the banks.

What is also known. Robert Richard Torrens, the Colonial Treasurer, was an active and strong supporter of the proposal.

Although Young realised that only Royal approval could initiate a move to establish a mint, he was also aware that the survival of the colony was at stake.

He found a loophole in the legislation. While the Governors were not allowed to assent in her majesty’s name to any bill affecting the currency of the colony, an accompanying paragraph that stated … “unless urgent necessity exists requiring such to be brought in to immediate operation”.

The “urgent necessity” clause paved the way for the South Australian Legislative Council to pass the 1852 Bullion Act.

A special session of the Legislative Council was convened on the 28 January 1852.

An enactment was proposed that allowed the Assaying of gold into ingots; the Council seeking to deflect Royal disapproval by striking gold ingots rather than sovereigns.

The ingots were intended to form a currency that would back the banknote issues of the banks as if they were gold coin. And be used by the banks to increase their note circulation based on the amount of assayed gold deposited.

The Act was as daring, as it was contentious, in that it made the banknotes of the three South Australian banks a Legal Tender, under specified conditions.

It drew condemnation from the eastern states. Melbourne’s Argus condemned the Act as dangerous, radically unsound and interfering with the natural laws of commerce. But these protests were motivated by self-interest, as South Australia posed a real threat to the Victorian economy by re-directing capital and labour away from the Victorian gold fields.

The Bullion Act No 1 of 1852 has a record unique in Australian history. A special session of Parliament was convened to consider it. Parliament met at noon on the 28 January 1852. The Bill was read and promptly passed three readings and was then forwarded to the Lieutenant Governor and immediately received his assent.

It was one of the quickest pieces of legislation on record, with the whole proceedings taking less than two hours.

Thirteen days after the passing of the Act, on 10 February 1852, the Government Assay office was opened. Its activities were supported by a state government initiative to provide armed escorts to bring back the gold from the Victorian diggings.

By the time the first escort arrived, a second assay office had been established, and Joshua Payne was appointed die-sinker and engraver. By the end of August 1852, over £1 million worth of gold had been received at the assay offices.

The passing of the Bullion Act was a masterly stroke of legislature and played no small part in averting economic catastrophe and laying the foundation for a stabilised currency.

Leading numismatic author Greg McDonald expressed his views when he wrote. “That Australia is today viewed as one of the most desirable destinations on the planet is due, in no small part, in the ability of our forefathers to find an often analytical solution to a problem. The creation of these golden relics is a part of that ”can-do” ability that forged this nation”.

The Ingots took two forms.

The first issue was cast from gold, stamped on both sides. We refer to it as the Type I Gold Ingot and three examples survive today.

The second issue reflects a more sophisticated process and used a rolled gold planchet. We refer to it as the Type II Gold Ingot and five examples survive today.

Both the Type I and Type II Ingots are included in this Collection.

Each comes with a remarkable provenance and each is the only known example privately held.

Understanding the Ingots.

The Government Assay Office Gold Ingots were issued in South Australia under authority of the 1852 Bullion Act of the Province. They were made from gold dug from the Victorian gold fields.

Crude. But functional.

The Ingots were stamped with the official Government Crown Seal and showed their weight and their gold fineness.

The Ingots could be exchanged for banknotes at the rate of £3/11s per ounce. They could also be used by the banks to support their note issue, just as if they were gold sovereigns.

They were individually made with variations in the shape, the thickness and the positioning of the information.

By their very nature therefore, each Ingot was unique.

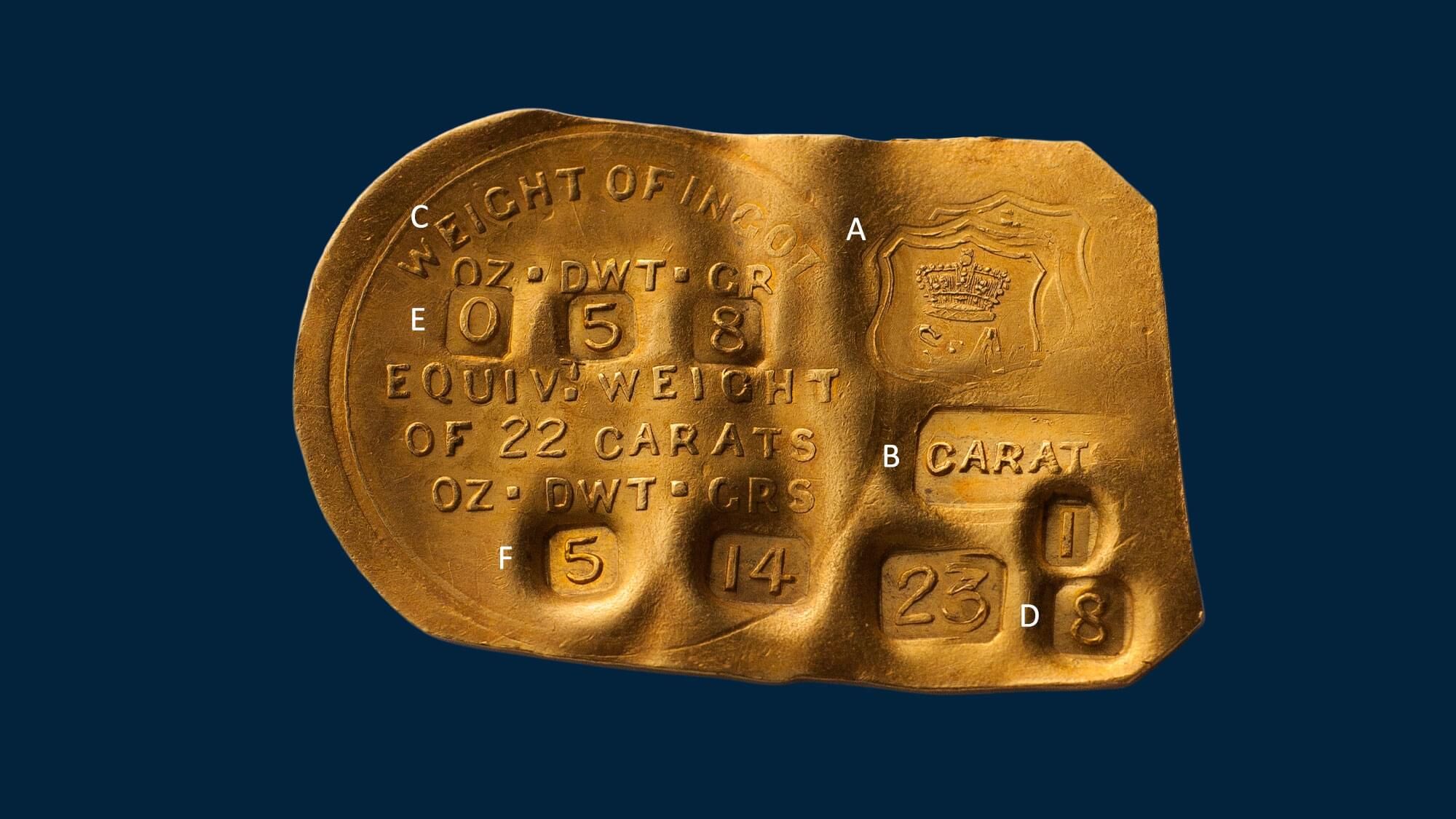

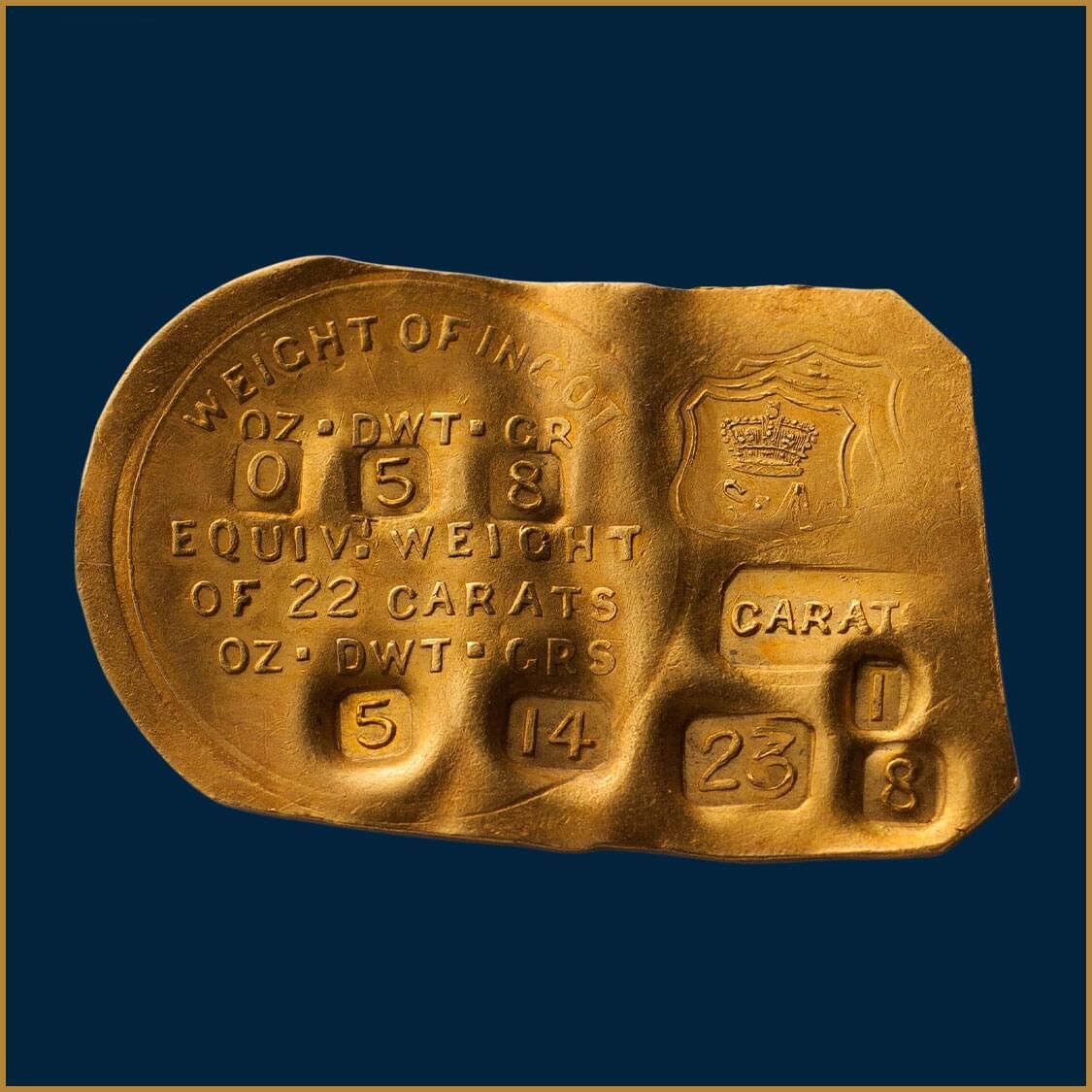

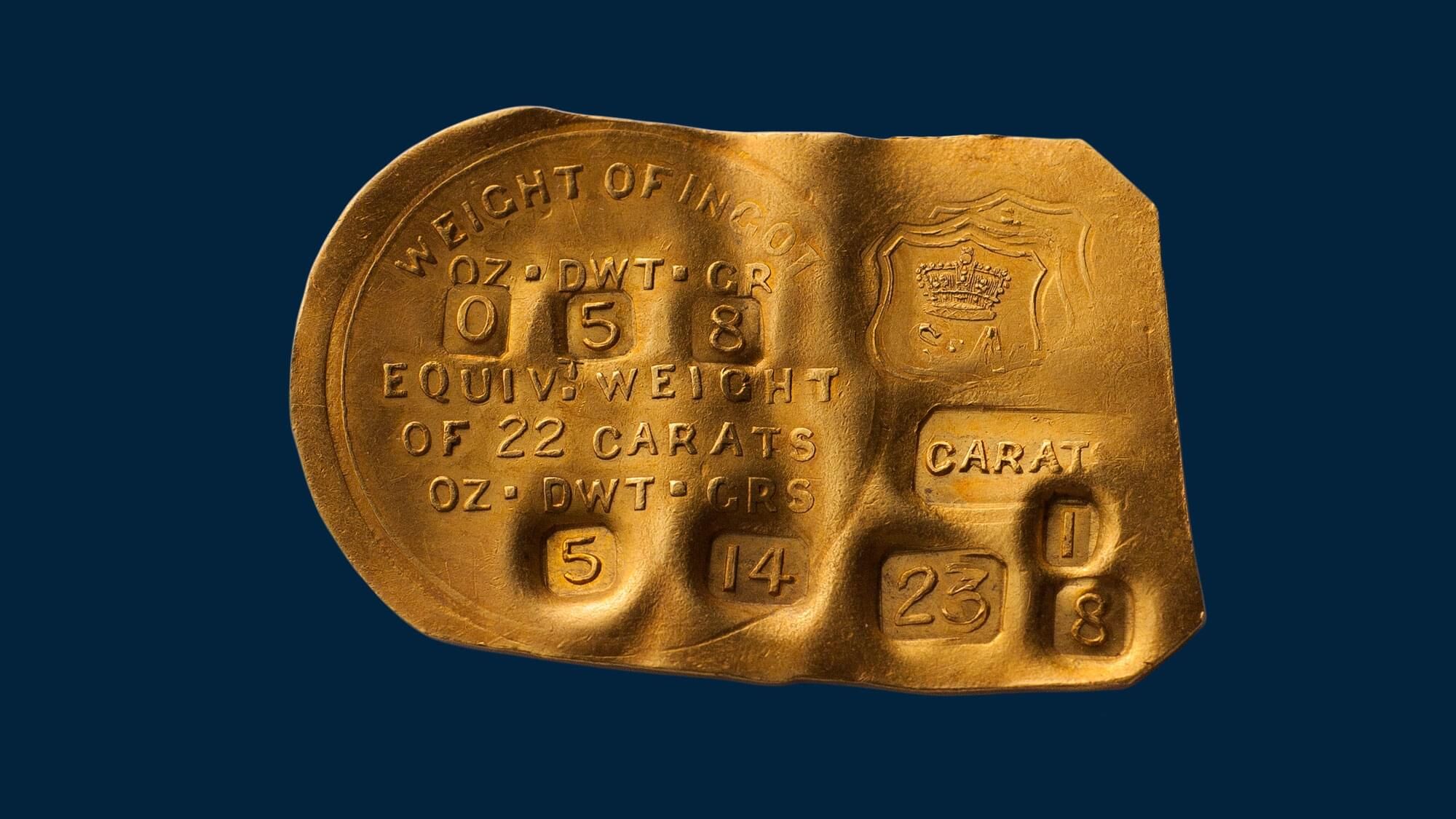

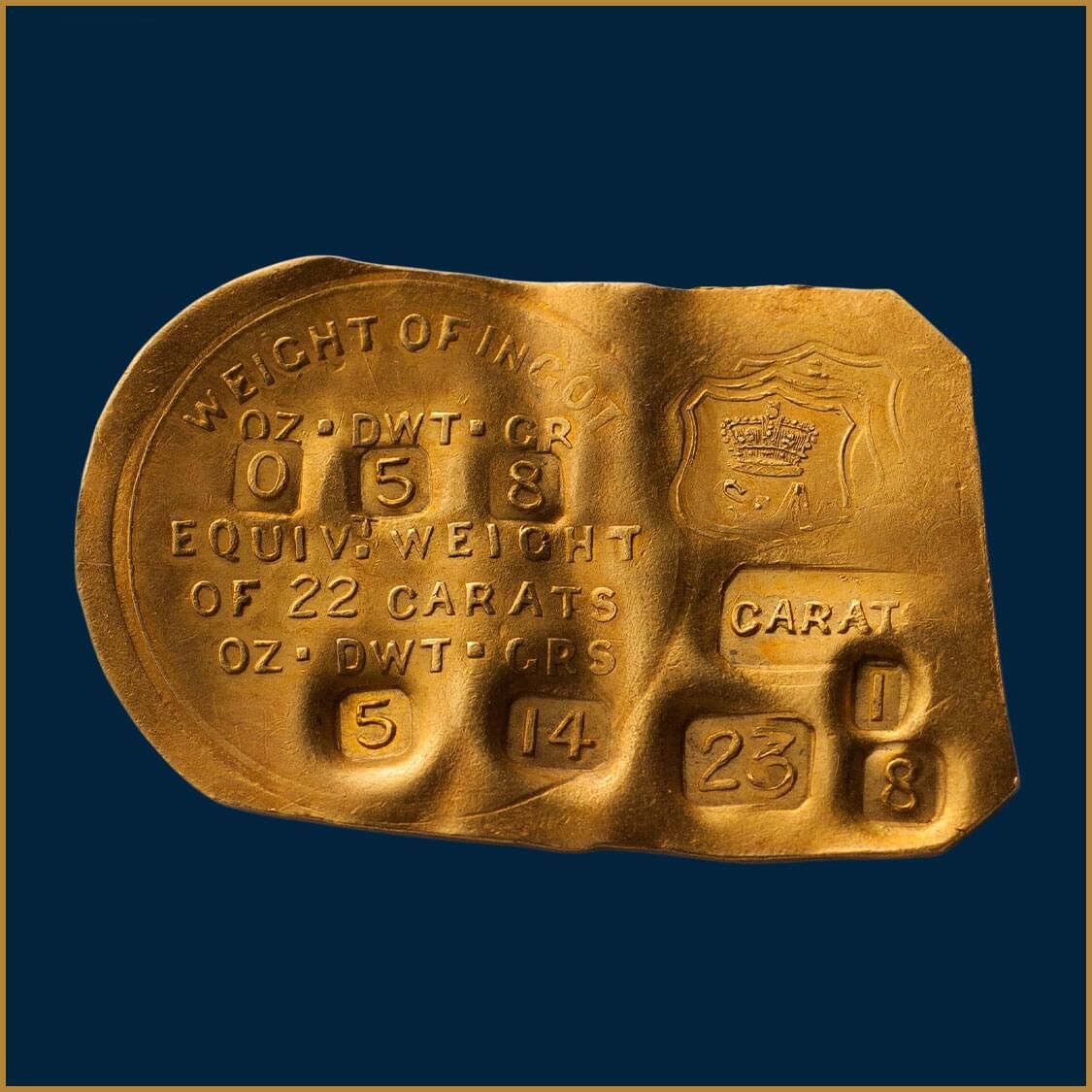

However, there is information stamped onto the Ingots that is common to all issues, noted as points A, B and C on the photographs.

A. A Crowned S.A. within a double linear shield being the Government Authority of South Australia.

B. The word CARATS in raised letters on a sunken rectangular field with the corners bevelled.

C. Five lines of standard descriptive text that relates to the weight of the Ingot.

- WEIGHT OF INGOT

- OZ . DWT . GR

- EQUIV . WEIGHT

- OF 22 CARATS

- OZ . DWT . GRS

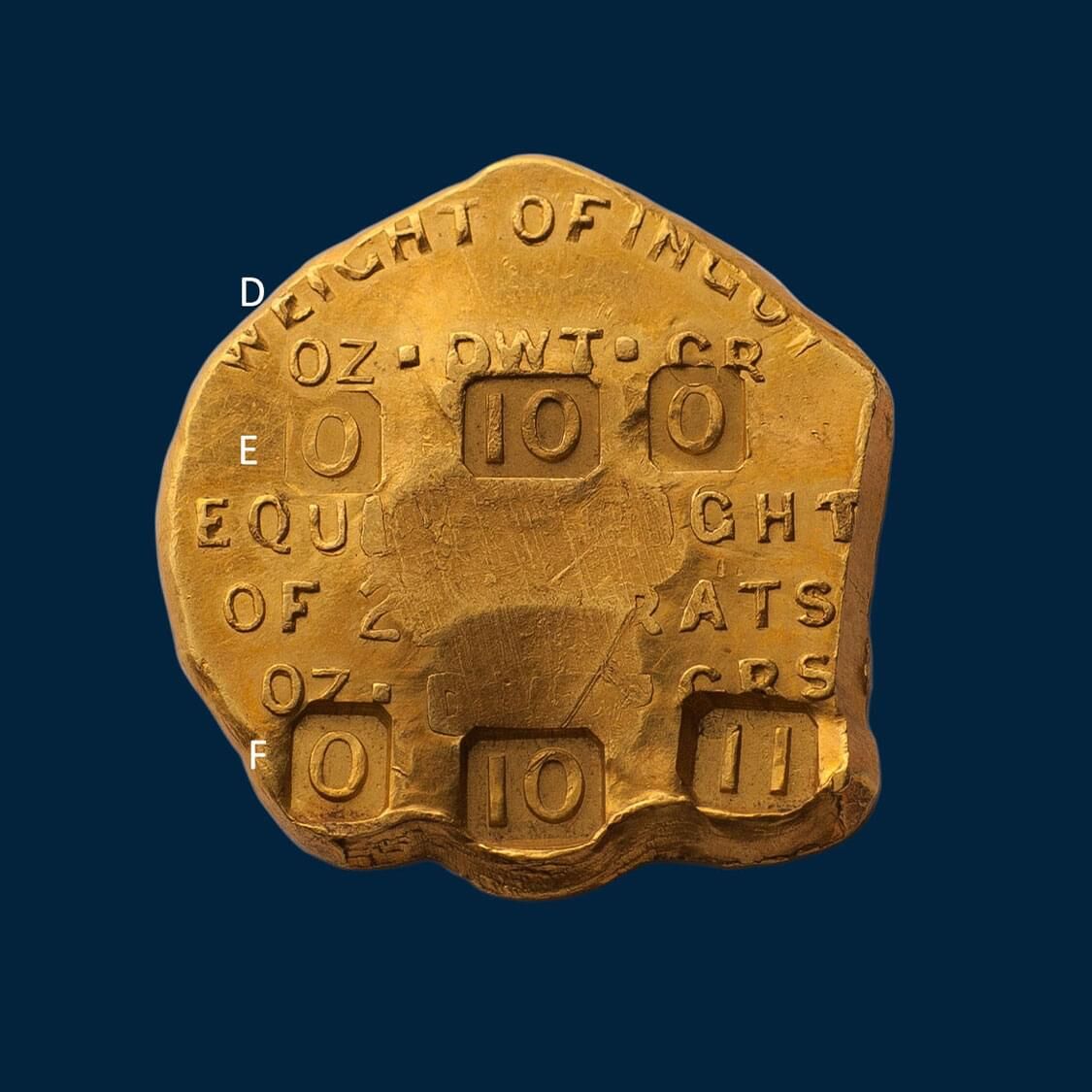

There is also information that is variable, specific to each Ingot noted as points D, E and F on the photographs.

The variable information was impressed onto the ingot by a square or rectangular punch: all the punches having their corners removed.

D. The fineness of the gold was impressed below the word CARATS.

E. Each Ingot was individually hand weighed and marked with its weight. The Ingot weight was stamped below the standard descriptive text WEIGHT OF INGOT and OZ. DWT. GR.

F. Each Ingot was also marked with a weight conversion to 22 carat gold. The 22 carats weight equivalent was stamped below the standard descriptive text OF 22 CARATS and OZ. DWT. GRS.

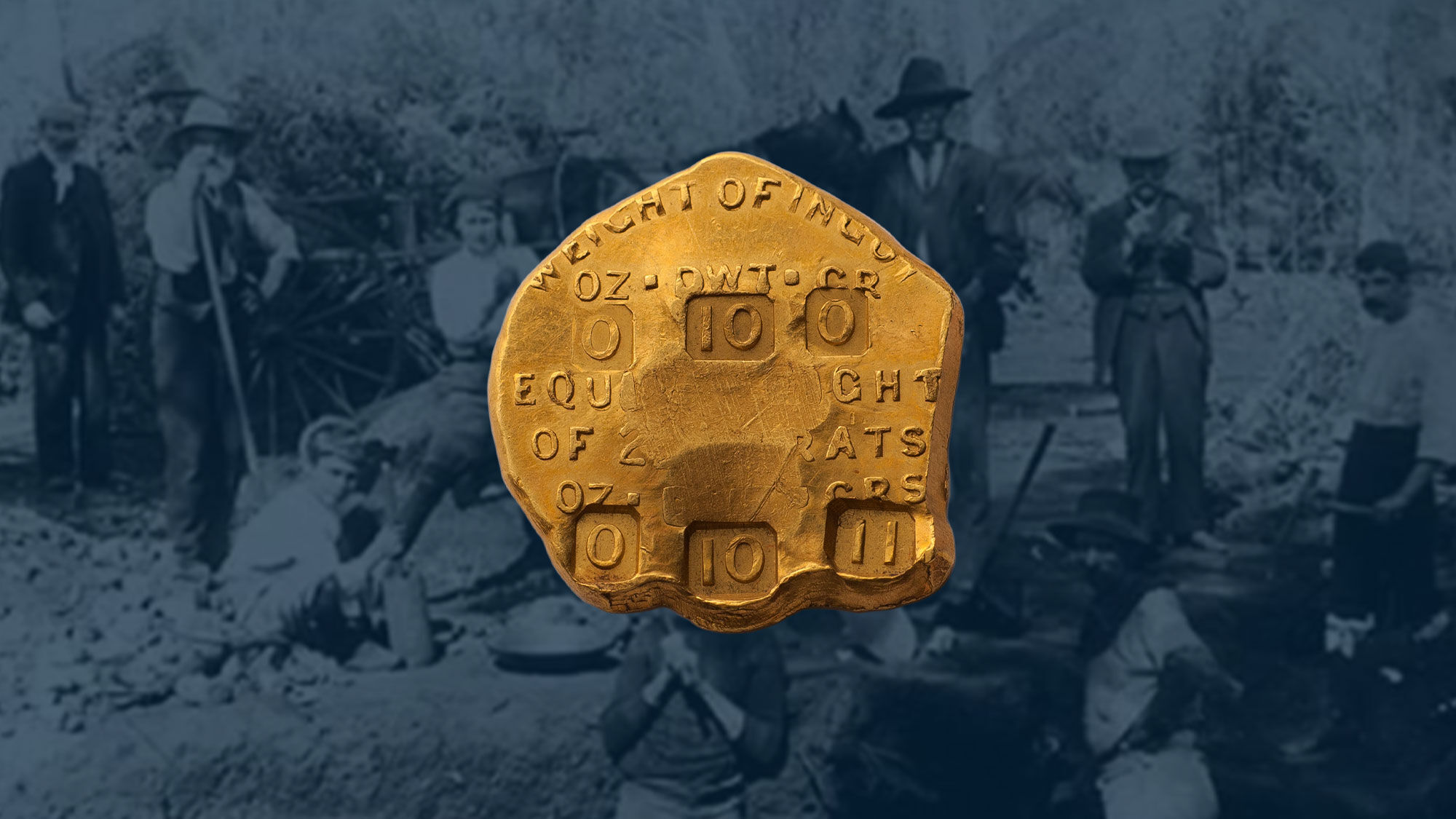

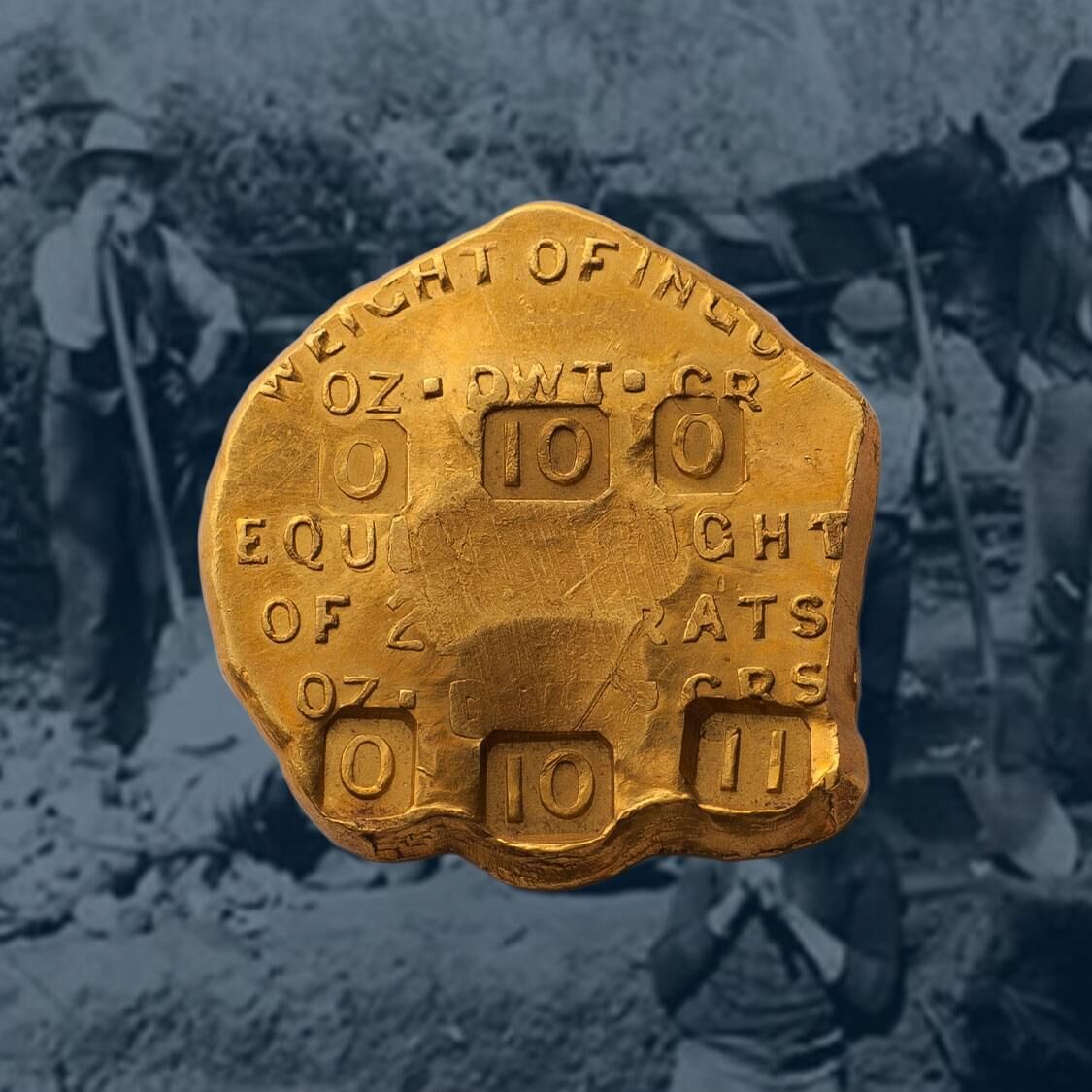

The Government Assay Office 1852 Gold Ingot. Type I.

This Type I Ingot is the only known example of its type privately held. Presented in a quality of Extremely Fine with technical reference, J. Hunt Deacon 3.

A pentagonal cast of gold dug from the Victorian gold fields, struck on both sides. Maximum length 24.97mm, maximum width 23.73mm, thickness 2.3mm, weight 15.54 grams. Bullion Act Value £1/17/1.5. Sterling Value £2/0/8.5.

Obverse:

The Authority Stamp of a crowned ‘SA’ within a double linear shield is depicted on the obverse, made slightly indistinct by the reverse punching of the ingot weight. The word CARATS in raised letters on a sunken rectangular field. Below the numeral 23, also in raised letters on a sunken rectangular field, indicating a gold fineness of 23 carats.

Reverse:

The reverse is comprised of five lines of standard descriptive text. And two lines of technical information that specifies the weight of the Ingot. Line 1. Standard descriptive text, WEIGHT OF INGOT, curved along the planchet edge and slightly off planchet. Line 2. Standard descriptive text OZ . DWT . GR. with square stops in between. Line 3. 0 10 0, being the technical weight of the Ingot expressed in oz, dwt and grams. Line 4. The standard descriptive text EQUIV . WEIGHT with square stops in between. Line 5. The standard descriptive text OF 22 CARATS . Line 6. The standard descriptive text OZ . DWT . GRS with square stops in between partly obliterated by obverse punching. Line 7. 0 10 11, being the 22 carats equivalent Ingot weight expressed in oz, dwt and grams.

Provenance:

First recorded public sale at Sotheby, Wilkinson & Hodge London 27 - 31 March 1922, the property of Baron Philip Ferrari de La Renotiere. Acquired by Virgil Brand (USA) lot 693 for £185. The Ingot later became the property of King Farouk of Egypt. Sold as part of the Palace Collections of Egypt by Sotheby & Co London 1954 when it was acquired by Spink & Son London on behalf of John J Pitman. The J. J. Pitman Collection was sold in 1999 by David Akers Numismatics Inc., the Ingot acquired by Barrie Winsor on behalf of Australian collector, Tom Hadley.

Type I Ingot - obverse.

Type I Ingot - reverse.

Exhibitions:

This Type I Ingot was displayed in 2001 at the opening of the National Museum of Australia, Canberra, as part of an Exhibition of gold artefacts from around the world. The opening of the Museum was the centrepiece of Australia’s Centenary of Federation celebrations.

The Ingot was also displayed in 2001 at the Museum of Victoria.

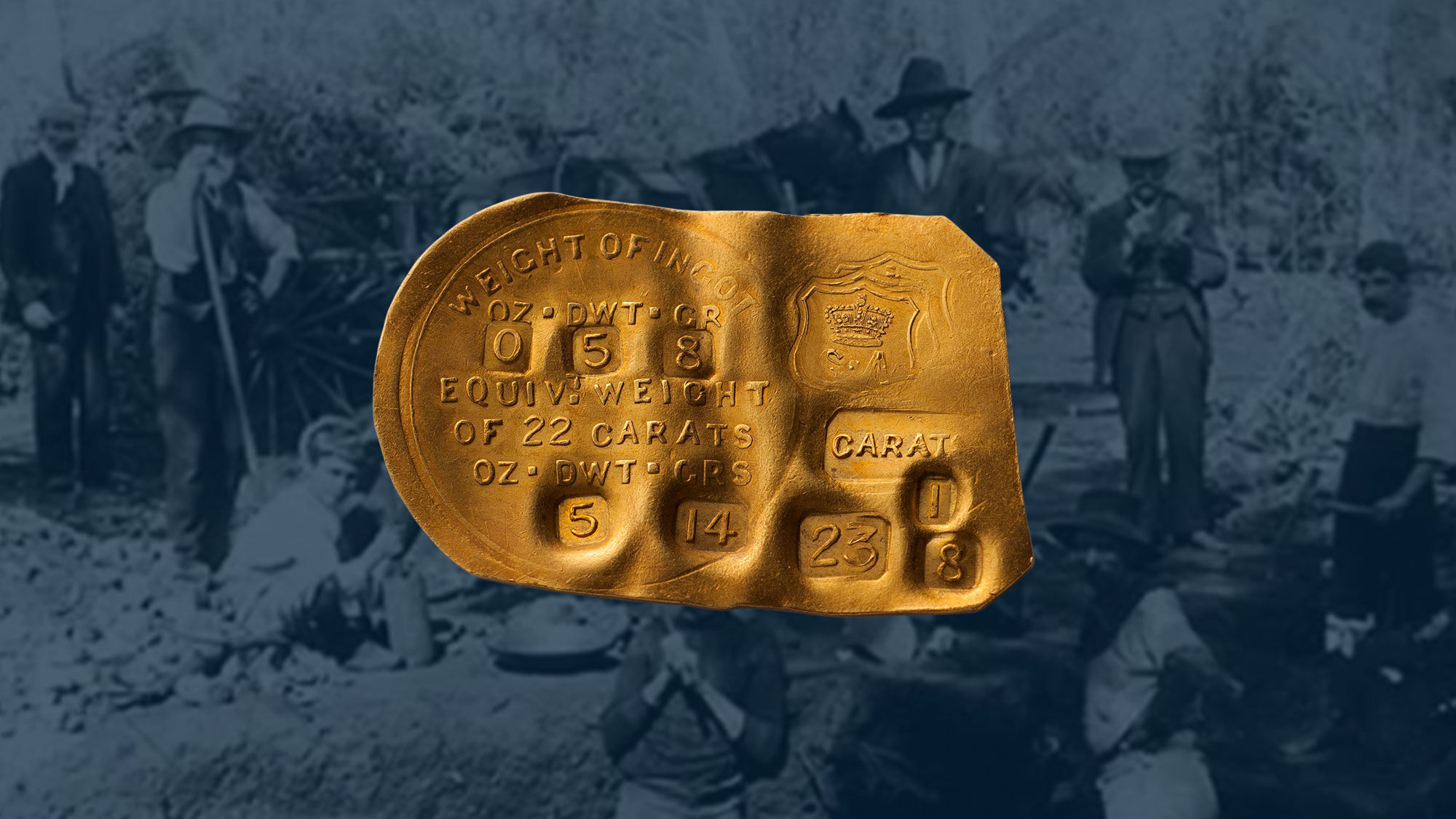

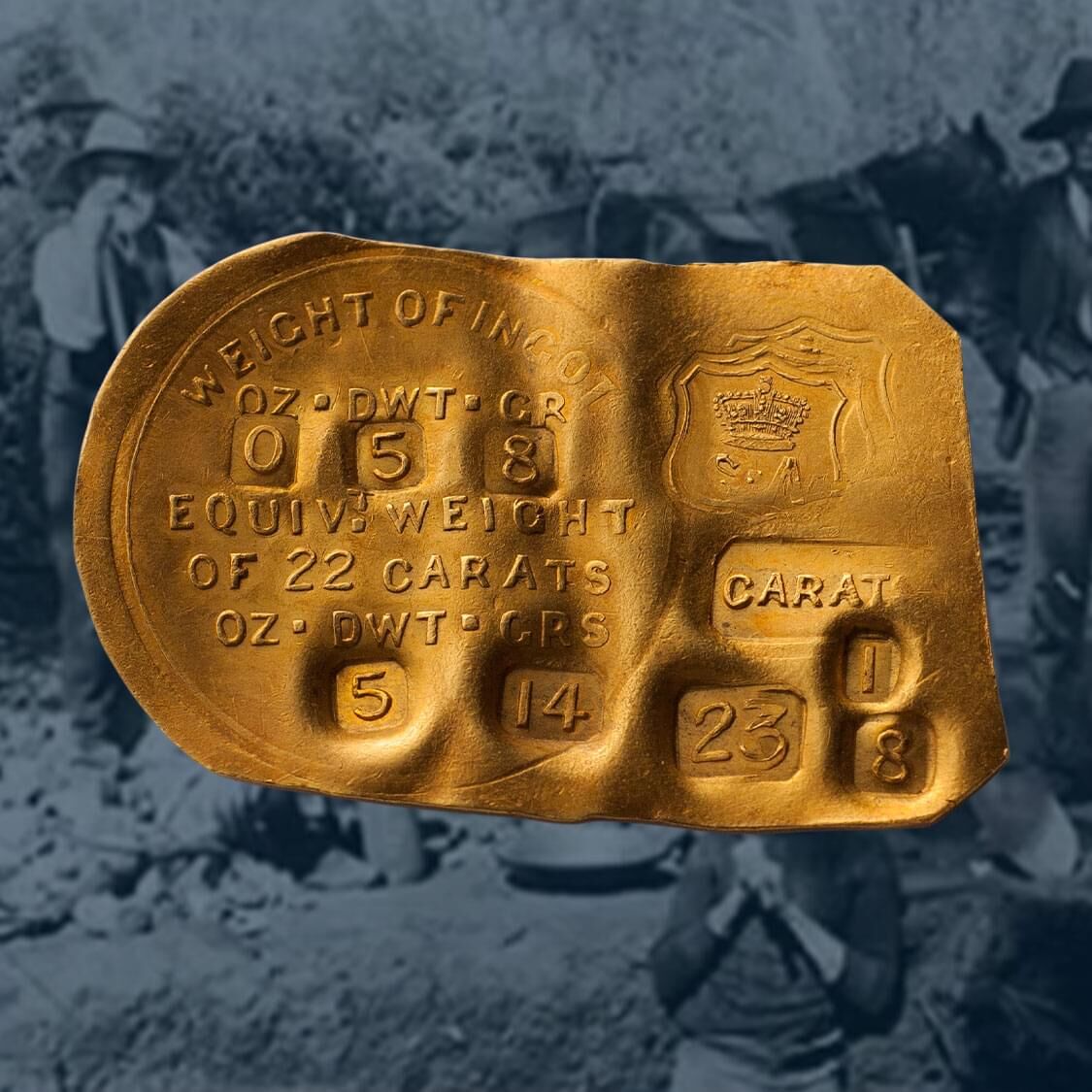

The Government Assay Office 1852 Gold Ingot. Type II.

This Type II Ingot is the only known example of its type privately held. Presented in a quality of Extremely Fine with technical reference J. Hunt Deacon 6.

A uniface oblong rolled gold Ingot, part rectangular with corners off. Struck on only one side. Maximum length 43.2mm, maximum width 27.6mm, thickness 1.2mm, weight 8.33 grams. Bullion Act Value £1. Sterling Value £1/1/11.

Obverse:

The Authority Stamp, a crowned ‘SA’ within a double linear shield, triple struck. The word CARATS in raised letters on a sunken rectangular field. Below, the numerals 23 and 1 over 8, also in raised letters on a sunken rectangular field, indicating a gold fineness of 23 1/8 carats.

To left, five lines of standard descriptive text. And two lines of technical weight information that specifies the weight of the Ingot. Line 1. Standard descriptive text, WEIGHT OF INGOT. Line 2. Standard descriptive text OZ . DWT . GR. with square stops in between. Line 3. 0 5 8, being the weight of the Ingot expressed in oz, dwt and grams. Line 4. The standard descriptive text EQUIV . WEIGHT with square stops in between. Line 5. The standard descriptive text OF 22 CARATS . Line 6. The standard descriptive text OZ . DWT . GRS with SQUARE stops in between. Line 7. 0 5 14, being the 22 carats equivalent Ingot weight expressed in oz, dwt and grams.

Reverse:

Blank.

Provenance:

First recorded public sale at Glendinings, London 21 - 23 November 1956, the property of Herbert W. Taffs M.B.E. Acquired for the Strauss Collection United Kingdom. Sold by private treaty in 1999 to Barrie Winsor on behalf of Australian collector Tom Hadley.

Type II Ingot – obverse.

Type II Ingot – reverse blank.

Exhibitions:

This Type II Ingot was displayed in 2001 at the opening of the National Museum of Australia, Canberra, as part of an Exhibition of gold artefacts from around the world. The opening of the Museum was the centrepiece of Australia’s Centenary of Federation celebrations.

The Ingot was also displayed in 2001 at the Museum of Victoria.

History of the Ingots and the 1852 Bullion Act.

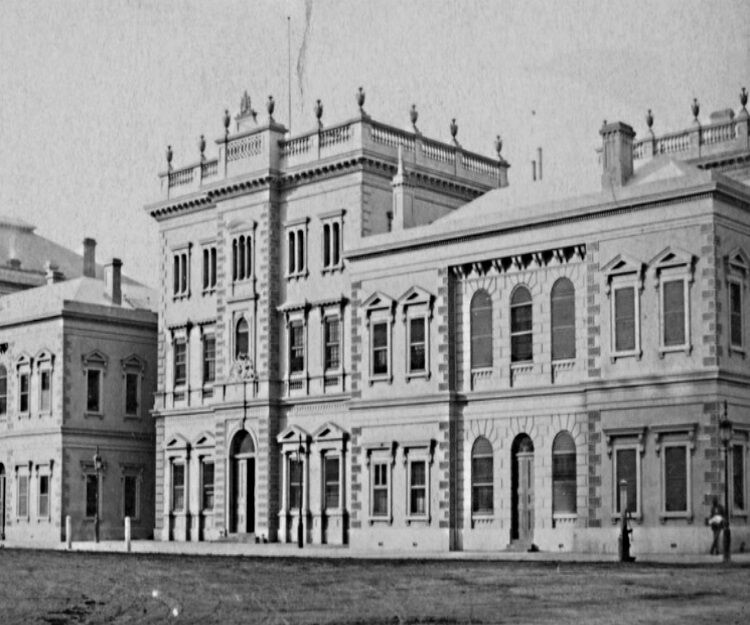

Original Treasury building, Adelaide.

The Government Assay Office 1852 Gold Ingots are the very first gold pieces struck for currency purposes in the colonies of Australia, issued in South Australia under authority of the 1852 Bullion Act of the Province.

The Bullion Act was enacted on 28 January 1852 and remained in operation for twelve months. To ensure that the Government would have a steady supply of gold, its price was fixed for the duration of the Act at £3 11s per ounce.

The Ingots could be exchanged for banknotes at the rate of £3/11s per ounce. They could also be used by the banks to support their note issue, just as if they were gold sovereigns.

The discovery of significant gold deposits in Australia in 1851 created sudden wealth and stimulated immigration on a vast scale.

It had a profound impact on Australia’s social and political development and underpinned the abandonment of the penal system on which the settlement of Australia was based.

The new-found confidence and a vastly increased population encouraged a national sentiment that accelerated the Australian colonies to unite and form the Commonwealth of Australia in 1901.

It is one of the most eventful and extraordinary chapters in Australian history, transforming the economy and society and marking the beginnings of a modern multi-cultural Australia.

Word of the discovery of gold spread like wildfire across the country and overseas. First was the rush to Ophir near Bathurst in early 1851 and the even greater rush to Ballarat in August of the same year.

Then in quick succession came the rich finds throughout central Victoria, Queensland, Northern Territory and finally the bonanza in Western Australia.

No colony was immune from the dramatic effects of the discovery of gold.

Those that were rich in gold. And those, such as the colony of South Australia, that was devoid of the precious metal. Its economy collapsed due to the mass exit of manpower lured to the Victorian gold fields.

Adelaide lost almost half its male population within the first three months of the first big gold strike near Ballarat. Also gone its cash resources. About two-thirds of the available coin travelled out of the state.

As the two main pillars of national activity, labour and capital, literally walked out, prices plummeted, property plunged, mining scrip nosedived, and Adelaide took on the air of a ghost town, with row after row of tenantless houses.

The cash-strapped banks pressed their debtors for cash payments, but as most debtors were merchants with their capital tied up, disaster beckoned.

By late 1851, genuine panic gripped those who had stayed behind as the total and complete insolvency of Adelaide looked real.

Out of desperation the Government offered a reward of one thousand Pounds for the discovery of a gold field in South Australia. None was found.

South Australia’s problems were further compounded because there was no method available to convert the gold nuggets the diggers had brought back from Victoria into a form that could be used for monetary transactions.

Calls were made for the establishment of a Government mint and the issuing of a coinage, but this was viewed as being in direct violation of the Royal Prerogative. Coining was beyond the powers and privileges of any local authority.

On 9 January 1852, over 130 leading businessmen met with a further 166 merchants met with Lieutenant Governor Sir Henry Young and pressured him to start up a mint to convert the raw gold into coin. The intention was that the mint would purchase gold from the Victorian fields at a higher price than paid in Melbourne.

There are some doubts as to who suggested an Assay Office and stamped bullion. What is known is that the establishment of a similar office had been introduced into the legislature of New South Wales in 1851. It was defeated mainly due to the opposition of the banks.

What is also known. Robert Richard Torrens, the Colonial Treasurer, was an active and strong supporter of the proposal.

Although Young realised that only Royal approval could initiate a move to establish a mint, he was also aware that the survival of the colony was at stake.

He found a loophole in the legislation. While the Governors were not allowed to assent in her majesty’s name to any bill affecting the currency of the colony, an accompanying paragraph that stated … “unless urgent necessity exists requiring such to be brought in to immediate operation”.

The “urgent necessity” clause paved the way for the South Australian Legislative Council to pass the 1852 Bullion Act.

A special session of the Legislative Council was convened on the 28 January 1852.

An enactment was proposed that allowed the Assaying of gold into ingots; the Council seeking to deflect Royal disapproval by striking gold ingots rather than sovereigns.

The ingots were intended to form a currency that would back the banknote issues of the banks as if they were gold coin. And be used by the banks to increase their note circulation based on the amount of assayed gold deposited.

The Act was as daring, as it was contentious, in that it made the banknotes of the three South Australian banks a Legal Tender, under specified conditions.

It drew condemnation from the eastern states. Melbourne’s Argus condemned the Act as dangerous, radically unsound and interfering with the natural laws of commerce. But these protests were motivated by self-interest, as South Australia posed a real threat to the Victorian economy by re-directing capital and labour away from the Victorian gold fields.

The Bullion Act No 1 of 1852 has a record unique in Australian history. A special session of Parliament was convened to consider it. Parliament met at noon on the 28 January 1852. The Bill was read and promptly passed three readings and was then forwarded to the Lieutenant Governor and immediately received his assent.

It was one of the quickest pieces of legislation on record, with the whole proceedings taking less than two hours.

Thirteen days after the passing of the Act, on 10 February 1852, the Government Assay office was opened. Its activities were supported by a state government initiative to provide armed escorts to bring back the gold from the Victorian diggings.

By the time the first escort arrived, a second assay office had been established, and Joshua Payne was appointed die-sinker and engraver. By the end of August 1852, over £1 million worth of gold had been received at the assay offices.

The passing of the Bullion Act was a masterly stroke of legislature and played no small part in averting economic catastrophe and laying the foundation for a stabilised currency.

Leading numismatic author Greg McDonald expressed his views when he wrote. “That Australia is today viewed as one of the most desirable destinations on the planet is due, in no small part, in the ability of our forefathers to find an often analytical solution to a problem. The creation of these golden relics is a part of that ”can-do” ability that forged this nation”.

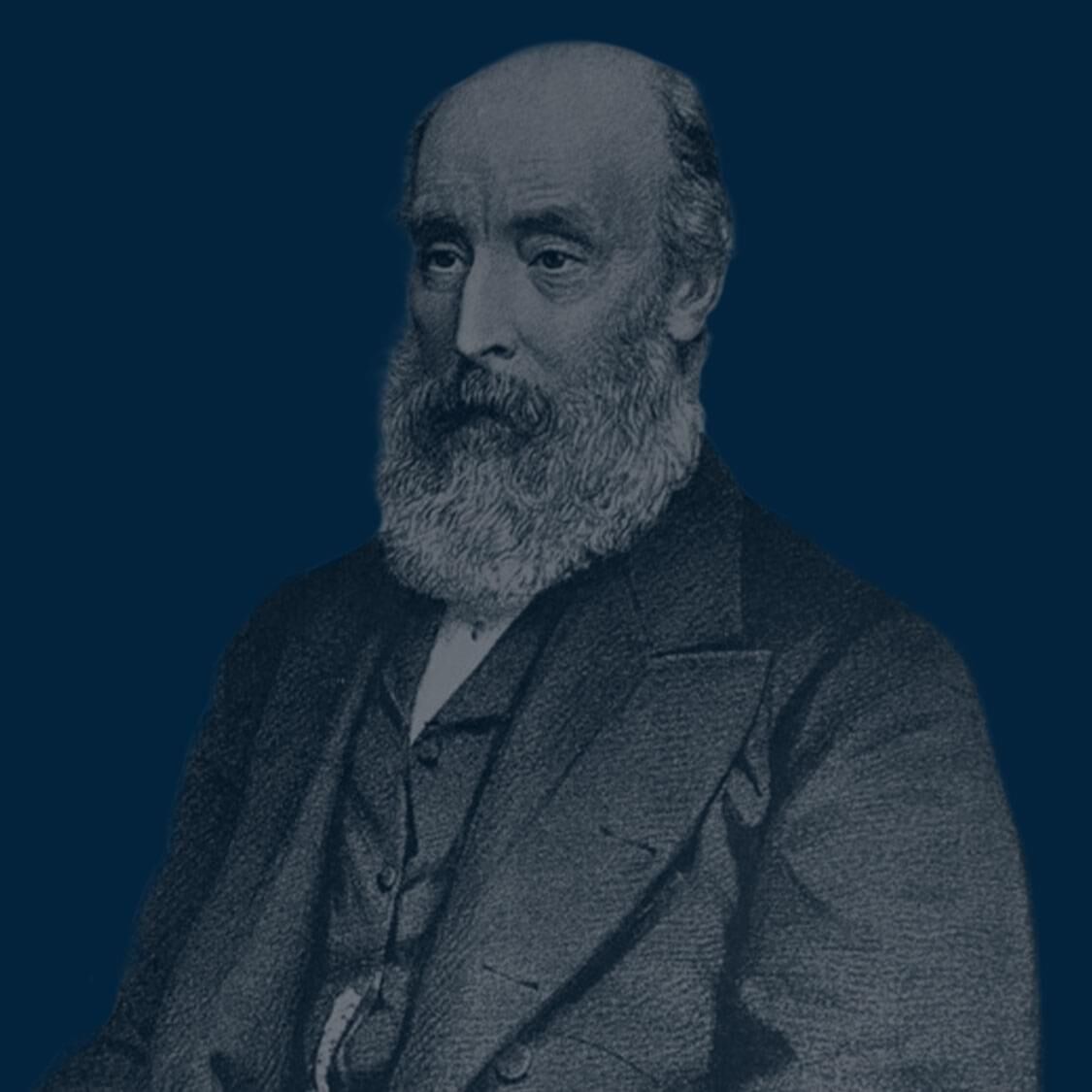

Sir Henry Edward Fox Young

Sir Robert Richard Torrens

© Copyright: Coinworks